What is a back three?

Teams that operate with three central defenders are said to play “with a back three”. This three-player line of defence is traditionally flanked on either side by wing-backs. These are responsible for pushing forward in attack, but then recovering back to create a back line of five when their team is out of possession.

Some teams will convert a four-player defence into a back three in possession, and then revert to a back four when defending. The most common way of converting from a four to a three is through a central midfielder dropping into the back line, either between or alongside the two central defenders. Both full-backs then push forward into the positions that wing-backs would normally take up. Alternatively, a back four can be converted into a back three with just one full-back moving forwards. The remaining three players then shift across to take up central positions as a back three.

Where does the back three originate?

Until the 1920s, two full-backs made up the defence in the popular 2-3-5 formation used by most teams. In 1925, however, a tweak to the offside rule changed things. No longer were three players needed between an attacker and goal for an attacker to be onside – only two were. It is this change that is thought to have influenced Herbert Chapman in establishing the W-M formation, in which an extra full-back was added to form a line of three behind two half-backs.

What does a back three do when their team is in possession?

A back three is often the shape from which teams build from the back, generally with all three players holding their positions in the central lane and the inside channels. The back three acts as support and protection inside the two wing-backs and underneath the midfield line. The middle of the centre-backs will often drop deeper or move higher to allow passes between the two wider centre-backs, enabling quick switches of play. It is also common for the wider centre-backs to attempt direct long passes towards the opposite wide area, while the three defenders will also need to play vertical passes into midfield or attack.

The centre-backs may also dribble into midfield to break the opponent’s press, especially if the opposition are facing them up with a two-man front line. This often means that the back three has a one-player overload in that line.

When facing a deeper block, the wider centre-backs can also provide crosses from narrow positions or make overlapping or underlapping forward runs. They can work with the wing-back and wide attacker to create overloads in wide areas and try to progress around the opposition block.

What does a back three do when their team is out of possession?

Three-centre backs provide strong cover and numbers at the back after any loss of possession, meaning the subsequent transition into defence should be easier. If a defensive midfielder has dropped in to create a back three during the build-up, however, this can weaken the back line during defensive transition.

The three central defenders predominantly deal with play inside the width of the penalty area, and are key when facing crosses. The extra centre-back adds extra presence in the middle to deal with deliveries from out wide. The two wider centre-backs can move out to defend the wider areas, especially when faced with through balls beyond the wing-back on their side.

Each of the defenders in a back three will also be required to step forward individually and press the ball in central areas, particularly when an opposition attacker drops or if an opponent breaks through midfield with a dribble. As one steps out, the other two must become more compact, keeping gaps in the back line to a minimum.

Which modern coaches have used a back three?

Lots of coaches use a three-man defence in the modern game. Here are some noteworthy recent examples of coaches to have used a back three in different ways.

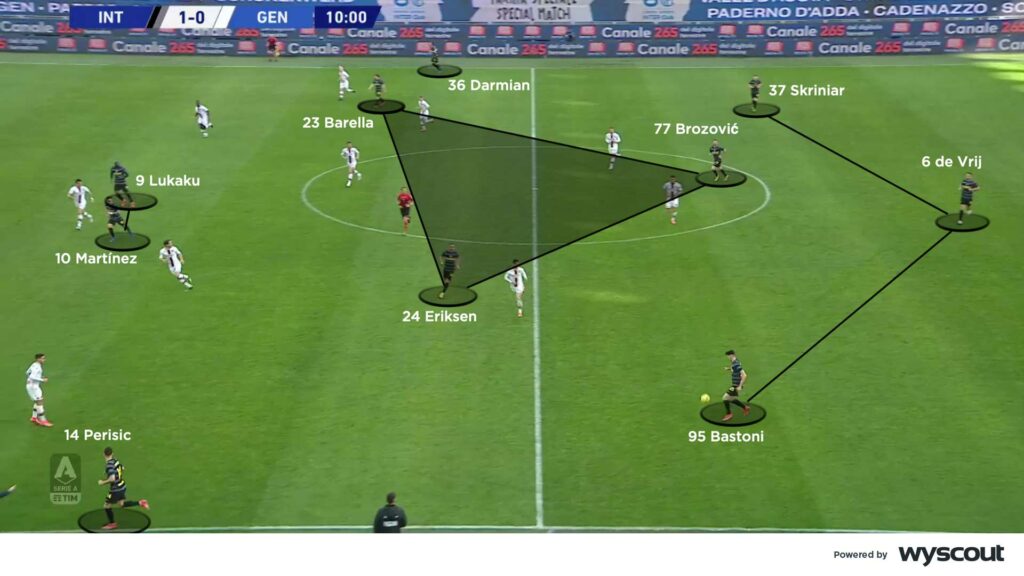

Antonio Conte, with Juventus, Italy, Chelsea and Inter Milan

Conte has used back-three systems throughout his managerial career. With Juventus, his 3-5-2 used supporting runs from the two number eights beyond the attackers, through the inside channels and central areas. His Italy team played a more direct brand of football, with the wing-backs moving higher in attack and the central midfielders moving wide to support them. With Chelsea, Conte used two narrow number 10s in support of a lone centre-forward. The wider centre-backs regularly advanced into positions alongside the double pivot, from a 3-4-3. With Inter Milan, he mainly utilised a 3-5-2 (above).

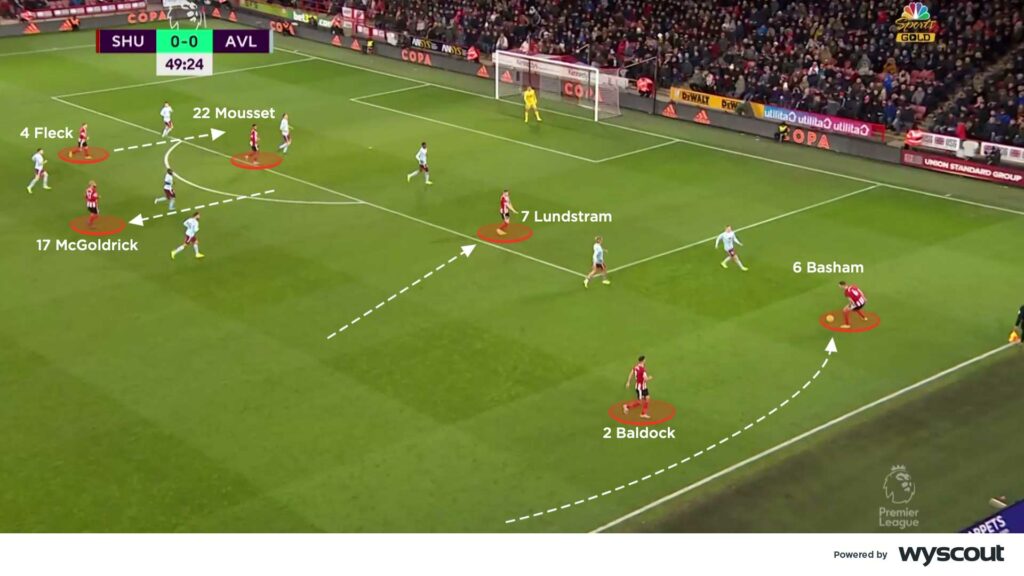

Chris Wilder, with Sheffield United

Wilder secured promotion to the Premier League with an expansive 3-5-2 that included unique overlapping centre-backs (above). With the team’s width provided by the wing-backs, Wilder’s single pivot midfielder dropped very deep. This movement acted as a trigger for one of the wide centre-backs to dribble or run forward off the ball. One of his centre-forwards would then drop deep to support the build-up, with the two number eights pushing forward through the inside channels or moving wide. Forward runs from the wide centre-backs could then be found through third-man combinations, mostly working around the outside of the opposition.

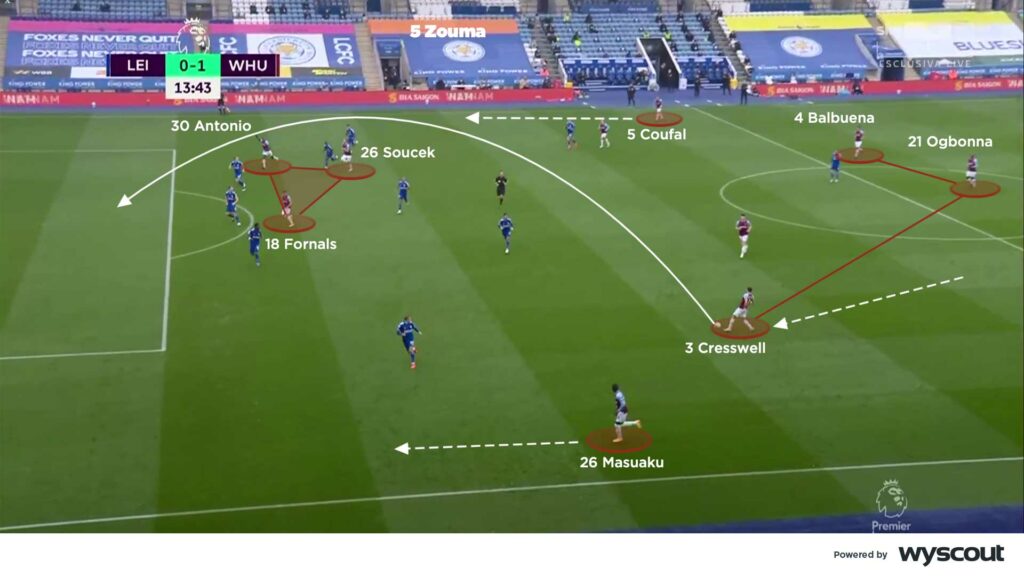

David Moyes, with West Ham

Moyes has used two full-backs on the same side, with Aaron Cresswell often used as a third centre-back behind a left wing-back, such as Arthur Masuaku. Cresswell provides added crossing threat from a deeper position (below), as well as underlapping runs. Arsène Wenger did something similar towards the end of his tenure at Arsenal, with Nacho Monreal as a third centre-back who provided underlapping attacking runs. Mikel Arteta has done the same with Kieran Tierney.

Pep Guardiola, with Bayern Munich and Manchester City

Guardiola has often built using a back three where both full-backs advance, and the single pivot drops into the back line, giving a stronger passing presence from deeper positions. Alternatively, he has utilised a back three where just one of the full-backs moves forward. Instead of moving into a wide position, they stay narrow and take up a position alongside the single pivot. This narrowed full-back joins midfield to create a diamond or box midfield in what is in effect a 3-4-3. Phillip Lahm for Bayern Munich and João Cancelo for Manchester City have played this role best. Kyle Walker, meanwhile, tends to hold his position to form a back three with the two centre-backs.

What are the benefits of playing with a back three?

Three centre-backs give extra cover and protection when defending, especially in central areas. The presence of an extra central defender also makes it easier to force play away from the centre of the pitch. The extra centre-back also helps deal with opposition crosses more effectively.

The extra centre-back can also improve wider defending in a deeper block, providing cover inside and behind the wing-back. Two central defenders are then still able to protect the central spaces if one centre-back moves out.

Similarly, should one of the back three jump to engage an opponent, the remaining two defenders can provide more cover and support than a single centre-back could from a central-defensive pair.

A back three can also provide an extra central passing option in the first line during the build-up phase and wide options for a switch of play. Both of these are useful when trying to beat a high press.

With two other centre-backs present, one can also step into midfield to create an overload or move wide in the opposition half to support the wing-back.

What are the disadvantages to playing with a back three?

Having a third centre-back removes a player out of midfield or attack. This could lead to attacking in underloaded situations more frequently.

The three defenders will naturally cover less space across the pitch compared to a back four. The spaces around the outside of a back three can thus be vulnerable, especially during counter-attacking moments. This means other players are needed in the wide areas when defending, so the wing-backs have to cover a lot of ground quickly to recover into defence. This in turn means that, after regaining possession, counter-attacks can lack width because the wing-backs will be behind play.