julen lopetegui

Sevilla, 2019–2022

Profile

Few managers have successfully rebuilt their reputations to the extent Julen Lopetegui did after a difficult 2018, when Spain sacked him on the eve of the World Cup for agreeing to join Real Madrid and Real sacked him four-and-a-half months later. The Spaniard has, since then, set an admirable example with Sevilla. In his first full season as their manager he gave them the identity that earned him such respect with Spain Under-21s, Porto and then Spain's senior team, and inspired them to qualify for the Champions League.

None other than the revered Monchi, their director of football, oversaw his appointment, which has given them a sense of stability perhaps absent since the departure of Unai Emery in 2016. "He needs to win," Monchi had said at their new manager's unveiling, and for all of the pressure he was under, Sevilla often have. The system that once made them one of Europe's best run clubs has been rediscovered.

Playing style

Lopetegui took the approach he oversaw with Spain Under-21s' successful European championship winning team of 2013 to Porto, where he was followed by Óliver Torres and Cristian Tello. Both teams employed a passing game, and favoured technically gifted players in midfield.

Porto developed a very attacking 4-3-3 formation with which they built from defence. Their defensive line sought to establish a quick link with the two pivots, Casemiro and Héctor Herrera, in midfield in an attempt to create an overload that in turn would contribute to their attacks; Casemiro and Hector also provided the defensive cover required for their influential full-backs Danilo and Alex Sandro to join attacks.

A further, consistent feature of one of Lopetegui's teams is his employment of a false nine or withdrawn striker to draw a central defender out of position and create an imbalance in opposing defences. Yacine Brahimi, working with his back to goal before combining with those around him, fulfilled that role at Porto, who were also organised to apply an intense counter-press.

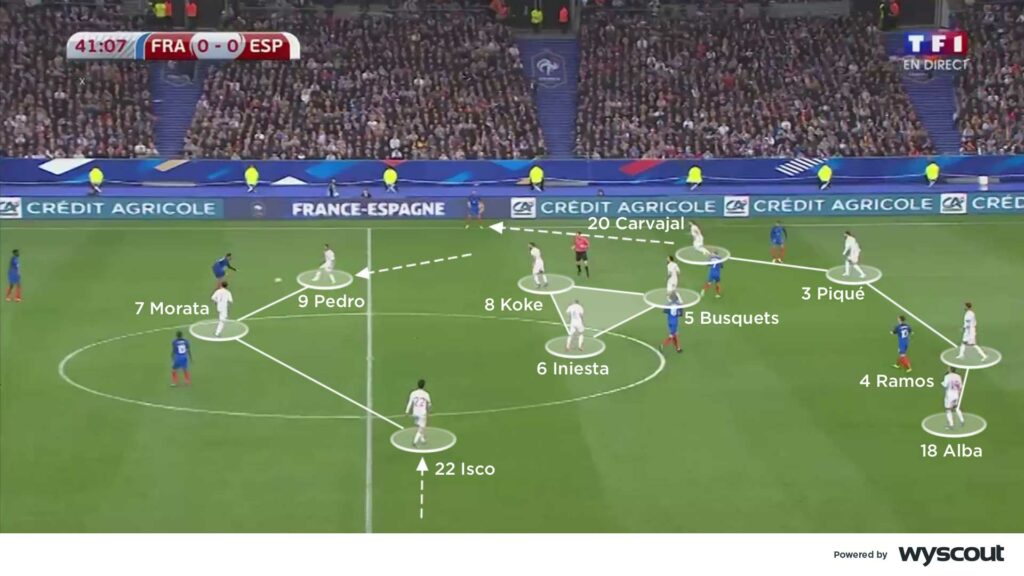

As Vicente del Bosque’s successor with Spain, Lopetegui rebuilt the national team without changing the identity that had brought them such success. They prioritised creating spaces in the inside channels – Isco, influential with Spain Under-21s, and David Silva became increasingly significant – from what was also a 4-3-3. If their build-up phases began with their goalkeeper David de Gea linking with the wide-moving Gerard Piqué and Sergio Ramos, playing in central defence between the advancing Dani Carvajal and Jordi Alba (below), in front of them Sergio Busquets worked to ensure that they remained balanced and to further that build-up.

Andrés Iniesta and Koke, playing either side of Busquets in that midfield three, adopted narrow positions to create numerical advantages with their striker and at least one of the two wide forwards in front of them, all three of which offered constant movements in an attempt to lose their markers and to encourage passes in behind. The passing approach led by Alba, Iniesta and Isco, often through the use of triangles, a third man, changes of pace and short passes, led to them retaining their desired overloads (below), and ultimately created their most consistent goalscoring opportunities.

Lopetegui attempted to apply a similar approach in his next position, at Real, but their 4-3-3 also often became a 4-2-3-1. Their full-backs, Carvajal and Marcelo, provided their attacking width so that those in more advanced positions could focus on finding spaces in the central areas of the pitch; where Carvajal sought to cross towards the far post, Marcelo favoured playing short to those infield.

With opponents working to limit those spaces and limit the passing options available to Isco, Luka Modric and Toni Kroos, Real would play short passes until the spaces they sought appeared. Modric and Karim Benzema complemented those efforts – Kroos often withdrew to alongside Casemiro – with movements designed to create those spaces.

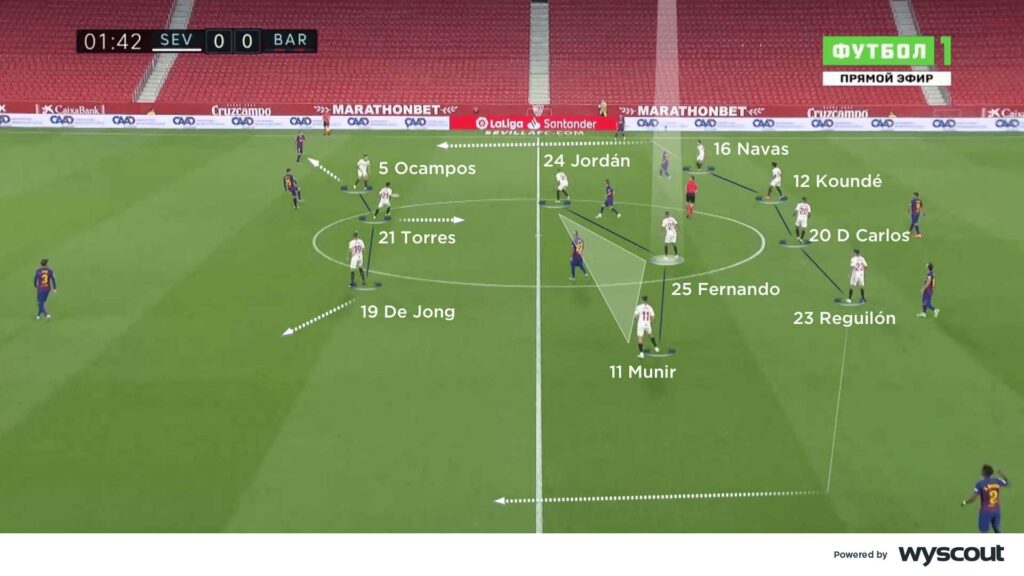

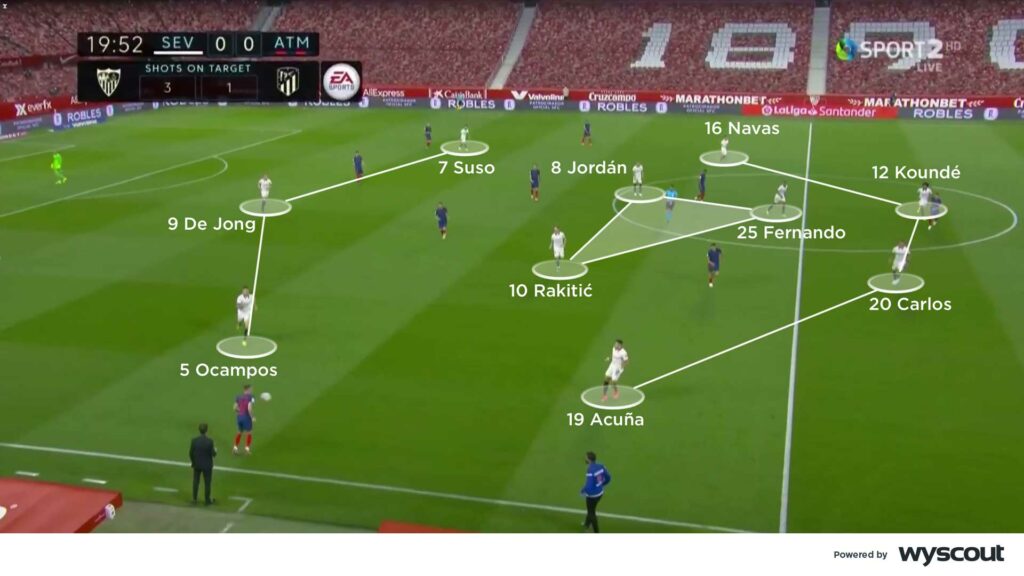

Sevilla have since been rewarded for giving Lopetegui the time Real would not. Again favouring a 4-3-3 (below) and a 4-2-3-1, they consistently demonstrate a sense of balance and a sound grasp of possession, and attack into the final third with options and overloads. When in possession they seek to slowly circulate the ball to create spaces in central areas. Fernando, their defensive midfielder, adopts a position between their central defenders to encourage progressing possession, often doing so in relation to the press their opponent is applying and in an attempt to create a three-on-two at the start of those attempts to advance.

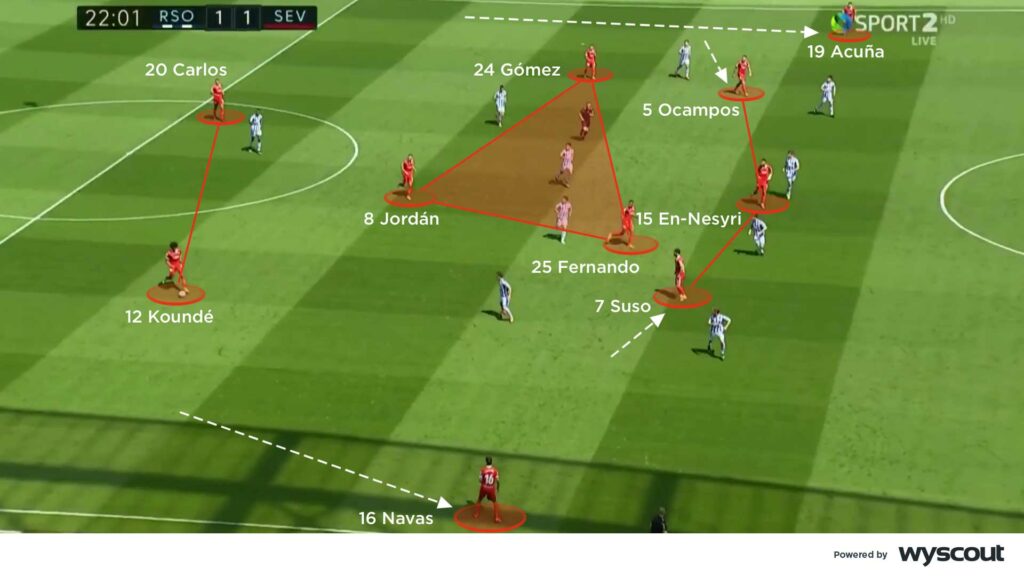

From midfield, there exists significant variety between Fernando, Joan Jordán, Óliver Torres, Ivan Rakitic and Papu Gómez, and to the extent that, when required, a double pivot is formed. Torres, Rakitic, Gómez and Jordán contribute to the combinations that unfold in central territory and, with full-backs Jesús Navas and Marcos Acuña overlapping, Suso and Lucas Ocampos drift into the inside channels where they work to escape their markers and to receive possession while facing forwards.

They consistently offer numerous options between the lines, and similar patterns of movement to those seen with Spain – combinations between full-back, central midfielder and wide forward, and overlapping runs from full-back to outside of those combinations. They are also offering an increased number of rotations between those in central midfield; they change the identity of their deepest positioned midfielder, particularly when building in the attacking half, without sacrificing attacking movements or their wide forwards' attempts to drift infield.

Their striker, similarly – and in contrast to with Porto – is increasingly moving wide to provide support and to create space for the movements Lopetegui is demanding through the centre of the pitch. Youssef En-Nesyri focuses on providing penetrative runs across opposing defences, instead of withdrawing into deeper territory; Luuk de Jong initially moves wide before preparing to attack crosses.

While their passing game impresses, Sevilla's intensity is their greatest strength and contributes to their balance. Navas and Acuña add a further layer in the final third, and are instructed to advance and either play crosses or passes in behind defences towards those contributing to the second wave of their attacks.

Pressing and defending

Lopetegui's teams demonstrate a similar consistency when they are without possession (above). Porto’s counter-press was complemented by a high and compact defensive block; that intense press was mostly applied towards wider territory in an attempt to force the ball outwards as they pressed, via a full-back, a midfielder and the closest defensive midfielder aggressively pressing the ball once their attackers had forced it into wider territory. Porto were also very effective at blocking passing lanes, an ability that, with their press, limited opponents' options. That their disciplined central defenders Maicon Roque and Iván Marcano worked to ensure that Lopetegui's favoured shape was preserved also meant that they consistently offered cover against direct play.

Spain pressed with a 4-3-3 (below) and, where possible, used a particularly organised high block in which every player was aware of which opponent he needed to mark. They also knew when an intense press was preferable to closing down spaces or directing opponents into specific areas to preserve their desired defensive shape and protect their central defenders. If a mid-block was required, they reorganised to adopt a 4-1-4-1; whether defending with a mid-block or pressing into their attacking half, they offered a similar wider press to Porto's. It was most commonly a wide forward who instigated that press (below); when he moved to take an opposing central defender or defensive midfielder the full-back behind him advanced and aggressively applied the press's second phase, and their midfield three covered passes back infield. With their striker working to prevent switches of play, the spare wide forward moved infield to remain ready to engage from behind the striker.

Wide players who favoured occupying more central positions – Isco was prominent among them – proved capable of effectively contributing to Spain's counter-press in the centre of the pitch, where they aggressively responded to losses of possession. Those wide players were often joined by their striker, and potentially full-backs, in contributing to possible regains, which not only owed to their aggression, but their organisation and ability to block and intercept passes. The presence of agile midfielders with the ability to quickly accelerate and pressure the ball carrier ultimately complemented that.

Sevilla's defence is organised similarly to Porto's and Spain's. They mostly favour a 4-1-4-1 and a mid-block, or a high press from a 4-3-3, but the versatility of their central midfielders means that those midfielders are given different instructions – they therefore occasionally adopt a double pivot and a 4-2-3-1 to increase the cover that exists in front of their central defenders and from behind their full-backs when those full-backs advance.

From their more consistent 4-3-3, one attacking central midfielder – most commonly Torres or Rakitic – advances to join their striker in pressing their opposing central defenders. In another subtle change, their wide forwards then take their opposing full-backs; similar applies from their 4-2-3-1, when their number 10 advances to alongside their striker.

An out-of-possession 4-3-3 has also unfolded with Sevilla's starting striker pressing both central defenders by himself, when their wide forwards again prioritise their opposing full-backs. By that first press being curved outwards, play is locked towards one side of the pitch, where the relevant wide forward and full-back then engage while their midfield three retain their positions to provide a screen in midfield.