quique sanchez flores

Getafe, 2021–

The recruitment, for the third time, by Getafe of Quique Sánchez Flores brings the Spaniard back to where his managerial career began in 2005. He also briefly managed them in 2015, having since won the Europa League with Getafe's cross-city rivals Atlético Madrid. Six years after succeeding Cosmin Contra, Sánchez Flores is replacing Michel, who had struggled following José Bordalás' departure for Valencia, another of Sánchez Flores' former clubs.

"I wanted someone who knew the club, who knew me because it’s not easy to work with me," said Getafe president Angel Torres. "Someone who wouldn’t bring a radical change, so I thought of Quique."

Playing style

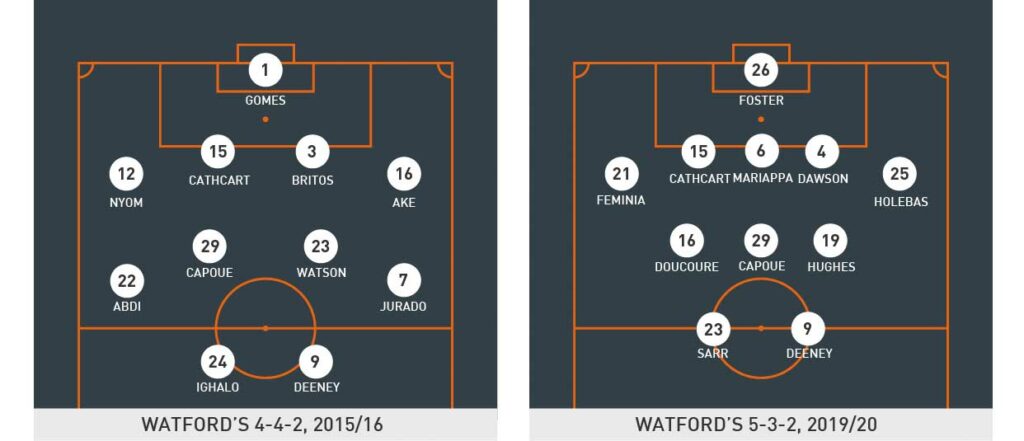

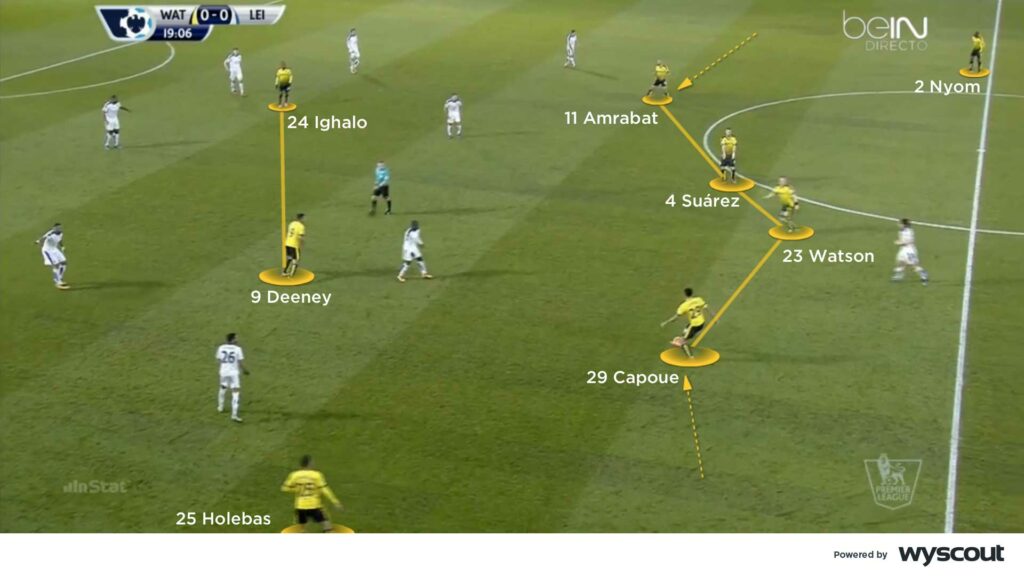

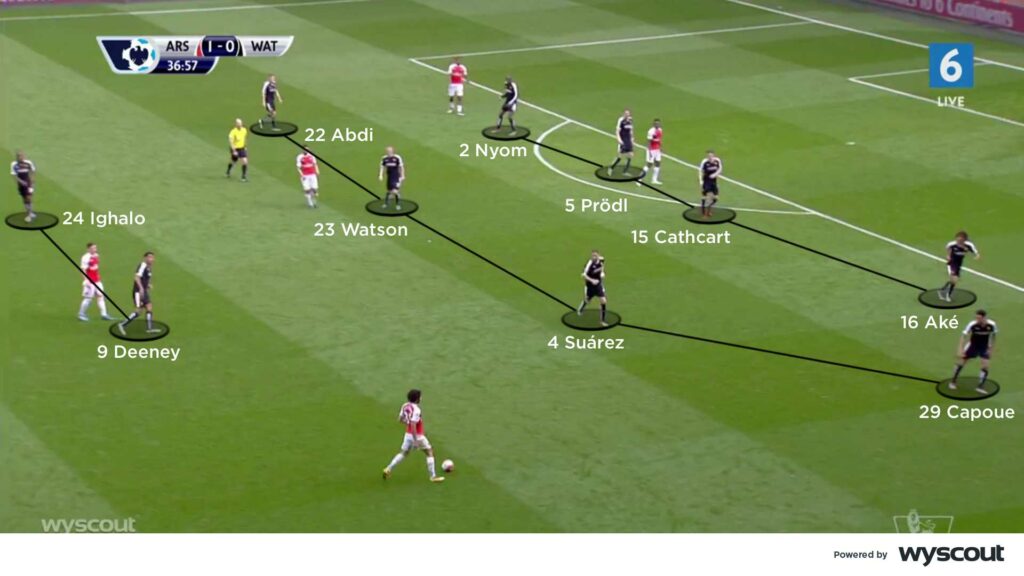

The 4-2-3-1 Sánchez Flores initially favoured in his first spell at Watford soon consistently became a 4-4-2 led by Troy Deeney and Odion Ighalo. As a consequence, however, they became somewhat predictable, and eventually their performances and results declined – opponents targeted Deeney's knockdowns and flick-ons and deprived Ighalo of space, undermining their attacking potential. Étienne Capoue and Valon Behrami were sometimes used as wide midfielders either side of two further, natural central midfielders in an attempt to increase their creativity, but their struggles persisted. There was also little support offered in the final third from their full-backs, so their attackers became increasingly isolated (below).

Their biggest match of 2015/16 – the FA Cup semi final against Crystal Palace in April 2016 – ended in defeat. It was noticeable that the same 10 outfield players had also started when they impressed in overcoming Liverpool 3-0 the previous December, before their decline had begun.

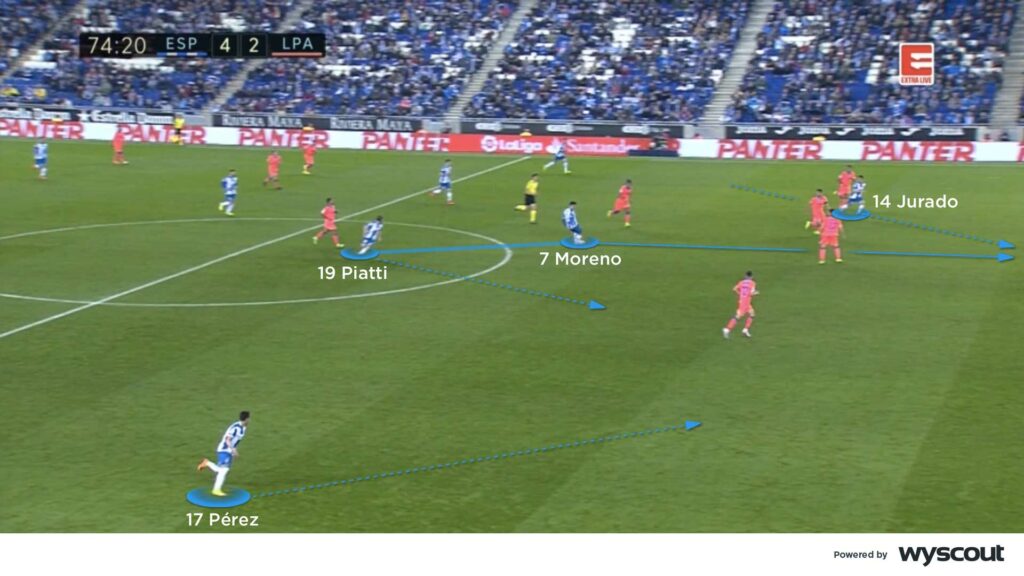

Sánchez Flores' departure from Watford was swiftly followed by his appointment by Espanyol. Similarly to at Watford he largely favoured a 4-4-2, but he also experimented with a 4-2-3-1, and unlike during his time in England, in Pablo Piatti, Hernán Pérez and José Antonio Reyes he had players capable of providing the quality his team required in the final third.

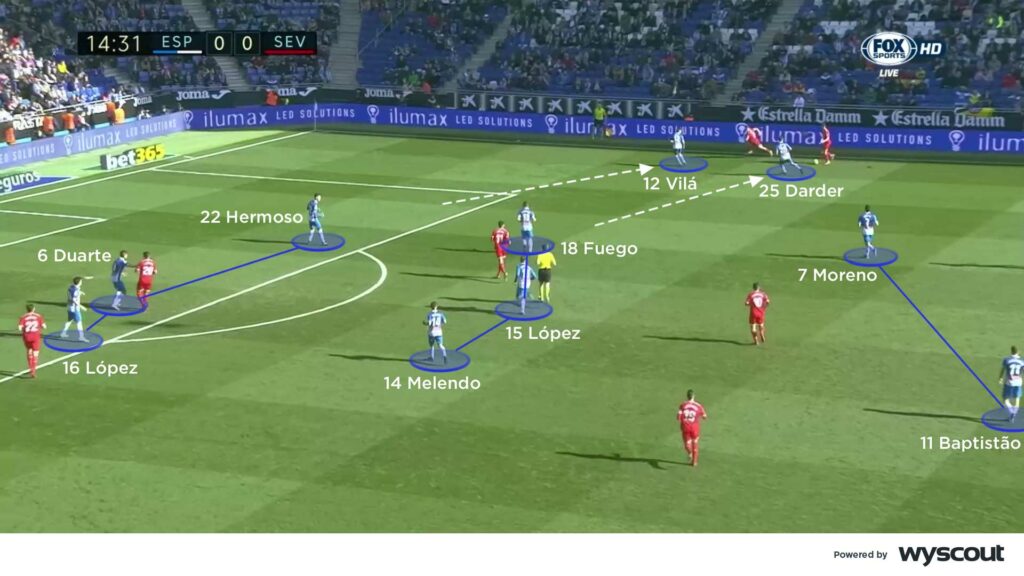

With their 4-4-2 their priority was again to create for their front two; in their 4-2-3-1 his attacking midfielders instead supported Gerard Moreno, their lone striker, by making forward runs infield, meaning that they often had a front four making penetrative runs (below). Their collective mobility meant that when transitioning into attack after regains they particularly impressed, and also led to rotations and eventually understandings that gave their attacks increasing flexibility. During 2017/18 he consistently favoured a 4-4-2 built on attacking XIs, but their results – not dissimilarly to during 2015/16 with Watford – again began to decline.

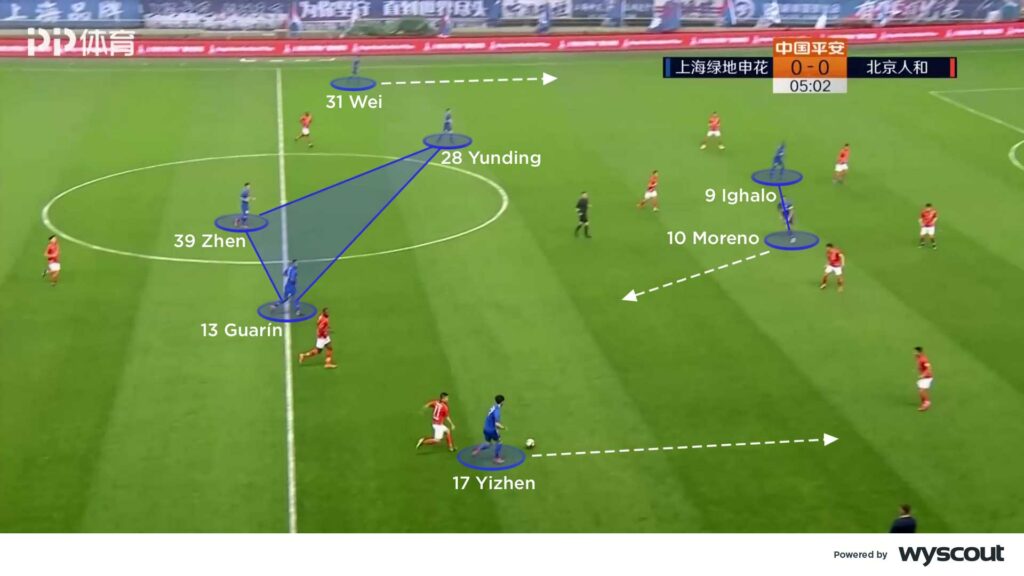

In December 2018 – the announcement was made on Christmas Day – he was recruited by Shanghai Shenhua, where his team prioritised working possession into the front two formed by Ighalo and Giovanni Moreno. As was also the case during his brief return to Watford in 2019, his favoured shape became a 3-5-2; Shenhua built around opposing blocks via their wing-backs before progressing possession back infield, often via more direct balls into the feet or path of their front two as they advanced in behind.

Fredy Guarín advanced from central midfield, both with and without the ball, to attack similarly to a number 10 by moving from the inside channels to where, in central territory, he could offer support, and to link play into Ighalo and Moreno via direct forward passes. His desire to move infield also created increased space for their wing-backs to overlap into. If he instead retained his position to assist in their attempts to build possession, combinations were used in wider territory, and Guarín complemented those combinations by delivering attacking crosses or passes back infield, potentially into whichever of their front two had withdrawn to receive away from the opposition's defensive line in the space that existed through Guarín's deeper position (below).

Pressing and defending

Watford were organised to defend with the same 4-4-2 (below) with which they attacked. They mostly did so via mid and low blocks but, regardless of their preference for defending from deep territory, they often lacked compactness and cohesion, and their front two offered minimal defensive presence or desire to shift across to provide a defensive screen ahead of those in central midfield, contributing to opponents regularly progressing into the attacking half. When that lack of compactness prompted their central defenders to step out to provide cover, further spaces were created for their opponents.

There also existed a lack of intensity when, as a team, they moved across the pitch, contributing to spaces forming in central territory that opponents sought to combine in and penetrate through. When their full-backs advanced to press they did so without sufficient cover and support, further stretching their central defenders; when they more successfully covered those central spaces, they became vulnerable to others in the inside channels, and their lack of compactness invited opponents to play direct, forward passes in behind.

Espanyol defended with a similar 4-4-2, but did so from slightly higher territory and most commonly with a mid-block. They were also significantly more compact, and therefore more capable of negating attempts from opponents to advance through the centre of the pitch, better protected by their front two, and as individuals astute at timing when to leave their positions to press.

They were more challenged when opponents took possession wide, where they were less consistent at tracking movement and runs. That their back four struggled to block crosses also enhanced an attacking threat they sought to overcome via their full-backs and wide midfielders pressing at an earlier stage (below), but at the expense of their defensive presence in central territory, and potentially the inside channels. There were also occasions when they appeared vulnerable against set-pieces.

A back five and an out-of-possession 5-3-2 (below) mid-block was instead favoured in Shanghai. While their front two sought to offer the same defensive screen witnessed among Sánchez Flores' best teams, their midfield three ensured increased cover of central territory, forcing possession wide – where Shenhua's wing-backs were more suited to jumping out to press, and did so in the knowledge that a back four remained in place when they did so.

For all of their compactness and the numbers and depth with which they defended, individual mistakes – they were unconvincing when attacking or reacting to second balls, while duelling as individuals, and occasionally when attempting interceptions or tackles – meant that they, too, were vulnerable.

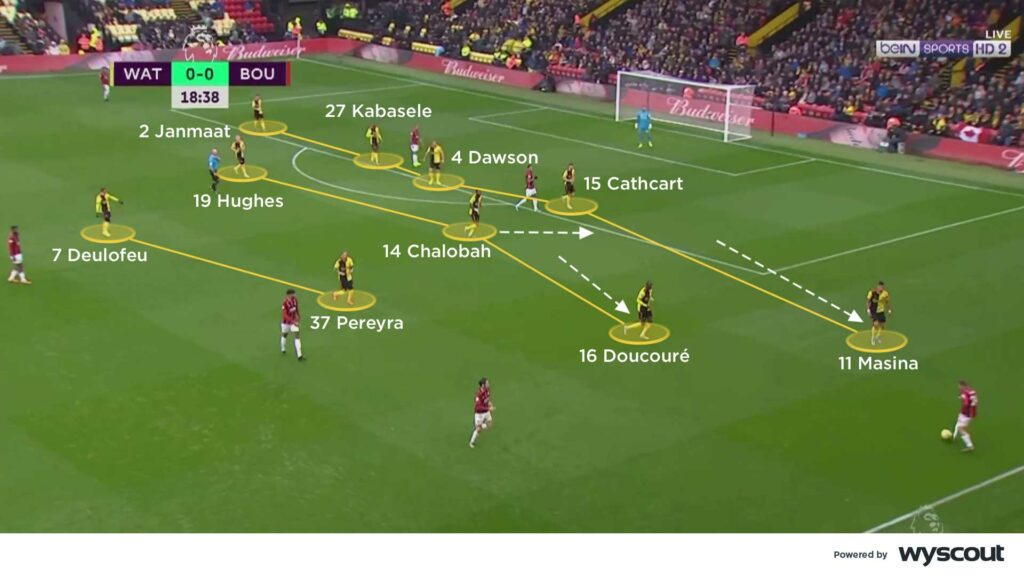

In his near three months back at Watford in 2019/20, Sánchez Flores favoured a 3-5-2 and a 5-3-2 defensive block (below), and also a 3-4-3 that meant they defended with a 5-2-3 or 5-4-1. The numbers and depth with which they defended made them more resilient across the width of the pitch, but undermined their ability to transition into attack.

Their wide midfielders joined their wing-backs in pressing into wide territory, preserving their defensive compactness, particularly from deep inside their defensive half and, because of their increased quality over those in Shanghai, they did so without committing the same individual errors.

Again the Spaniard instructed his front two to force play wide, where their wide midfielders supported the relevant wing-back. Behind them, the most central of their midfield three withdrew into deeper territory and remained ready to deputise in their defensive line if a central defender was required to drift across and cover for that wing-back.

Watford also defended with aggression, and the necessary willingness to move across the pitch and consistently apply pressure to the ball – not least when preserving the compactness missing during Sánchez Flores' previous spell as manager.