juanma lillo

Assistant Manager, Manchester City, 2019-2022 & 2023–

It was Juanma Lillo, one of Pep Guardiola's greatest influences, the Spaniard turned to when recruiting a successor as assistant manager to Mikel Arteta. They first worked together when Lillo managed Mexico's Dorados and Guardiola was still a player. Lillo had by then already become La Liga's youngest manager at the age of 29, when guiding Salamanca into Spain's leading division in 1995.

Lillo first joined City from China's Qingdao Huanghai, who he inspired to promotion to the Super League in 2019, and returns after a season managing Al Sadd in Qatar. “Juanma sees things no one else in the game sees,” said Guardiola upon the Spaniard's return. “He understands football on an incredible level, so he is the perfect person for me to work alongside.

“I have always been inspired by him – his knowledge of football, his intelligence and his humanity mark him out as a very special person in my life – and we have a shared ideology. He is a friend, a colleague and an inspiration. I am so, so happy he is back here at Manchester City.”

Playing style

Like all coaches, Lillo's methods have evolved, even if his understanding of football and his philosophy have remained consistent. While at Real Sociedad, from a 4-5-1 formation he favoured possession being played in central areas and offering numbers in wide areas with the intention of dictating play via their grasp of possession; at Almería, however, he introduced variants of a 4-2-3-1 and a 4-3-3, and experimented with a 3-5-2 and a 5-3-2 against opponents of the calibre of Barcelona and Real Madrid.

When working in Colombia, with Millonarios and Atlético Nacional, he showed his willingness to adapt to the abilities of those he inherited. He most commonly organised his teams into a 4-4-2, in which he had two defensive midfielders, or a four-diamond-two. In Japan and China, respectively with Vissel Kobe and Qingdao Huanghai, Lillo demanded his teams used a 4-2-3-1, or variants of a 4-3-3 or 4-4-2. Lillo's belief – not unlike Guardiola's – is that the longer the ball is in the opponent’s half and the closer his team remains to their opponent's goal, the likelier victory becomes.

He is often credited with favouring the 4-2-3-1 – a shape that encourages a team to consistently occupy attacking spaces with four players who remain options between and beyond opposing lines – before it became popular. The use, therein, of four attacking players contributed to the foundations of the positional play that Guardiola and Sampaoli are among those to have also since used; the numbers offered often lead to numerical or positional advantages. As can also be seen with Guardiola's teams, Lillo's often use short passes to draw opponents out of position and to create spaces elsewhere, often towards a free man; their focus becomes moving opponents to create increased spaces to advance into.

The use of a goalkeeper as an additional outfielder similarly encourages that – particularly against high-pressing opponents – while encouraging attacking players to remain advanced, as does his teams' desire to play with extreme width. The depth of possession can often be influenced by organised opponents; when those opponents move into narrow territory to defend the central areas of the pitch and against potential overloads, those out wide offer increased potential; if necessary, working possession to one side of the pitch draws opponents, and is followed by attacks on the opposite wing. City, and their relatively free-scoring wide attackers, regularly relished doing so even before Lillo's arrival.

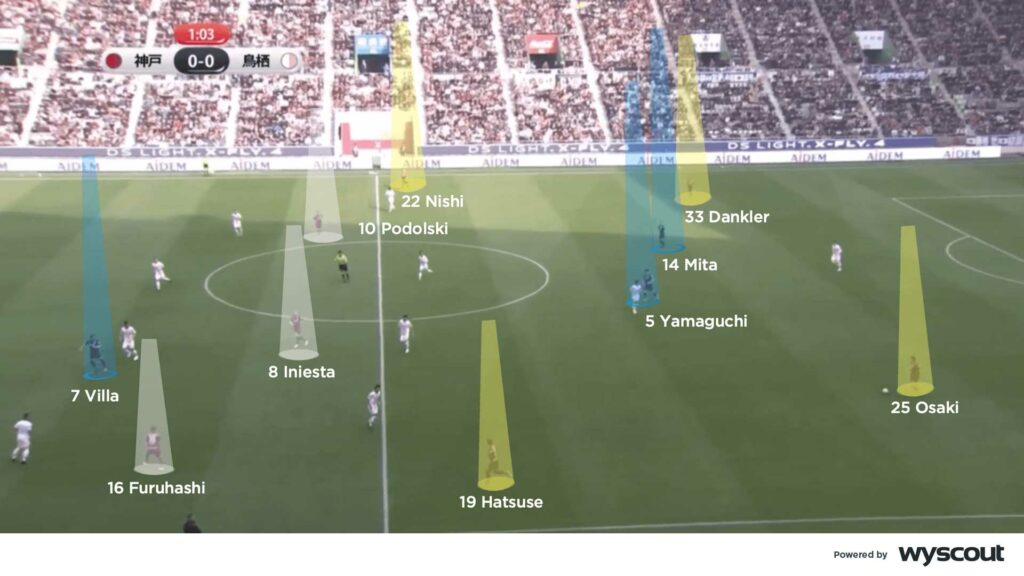

In Andrés Iniesta at Vissel Kobe, Lillo managed a player – and one who perhaps produced his finest football under Guardiola – capable of making a significant difference. He is likely even the greatest player Lillo has managed, and understood, in depth, the positional approach his manager sought, often making him the catalyst for their fluid approach. Their central midfielders prioritised adopting positions between the lines (above), and were able to achieve those positions because of the movements Iniesta and his fellow central midfielder, most regularly Hiritoka Mita, offered, and which largely connected their defence to their midfield and their midfield to their attack.

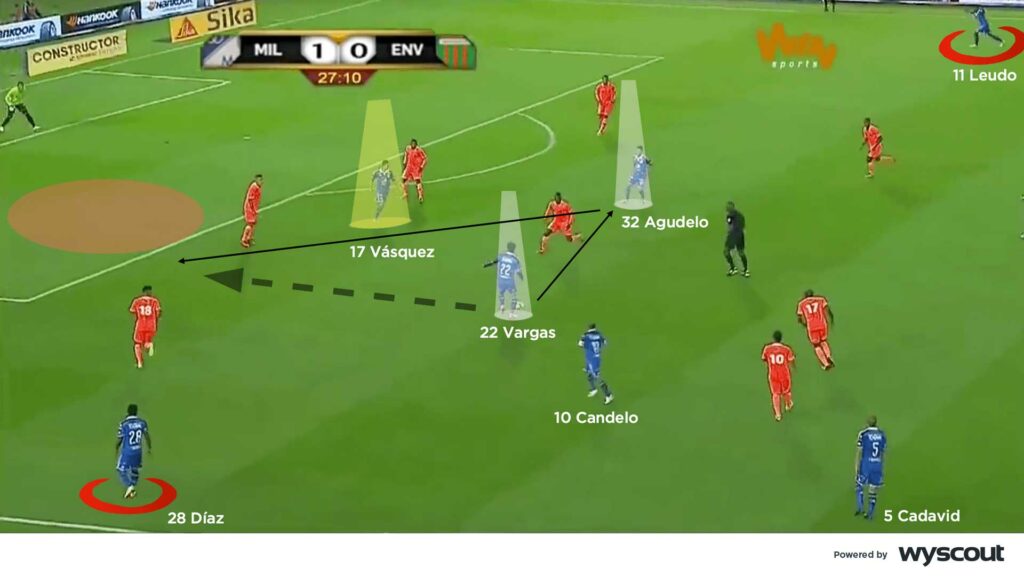

Those furthest from the ball combined to occupy further opponents and to contribute to the freedom that the ball carrier or those between the lines relished. Lillo encourages his teams to build attacks through passing, which often involves them pursuing lengthy passing sequences and combinations, and contributes to a sense of stability in possession. When that initial press has been bypassed, and more advanced spaces have been progressed into, Lillo's demand that certain players target those spaces and others prioritise combining in central areas owes to his desire to overcome the reduced time and space they will encounter there. Millionarios' full-backs, Leudo and Álex Díaz, provided their attacking width (below) so that those with the finest close control could operate inside, combine, and progress possession.

Pressing and defending

Lillo's preference to dominate both possession and specific territory is complemented by a quick and incisive counter-press. His teams' use of overloads and free men is advantageous during transitions when, if possession is lost, the immediate spaces are difficult for opponents to escape; if Lillo's teams have an overload, increased pressure can be applied to the ball, and the spaces around it can be defended with a numerical advantage.

Teams applying a counter-press – most commonly favoured because they can encourage direct regains as well as force mistakes and inaccurate passes – can be particularly assertive by seeking to directly duel and dispossess opponents by using several players to quickly engage with the ball carrier. Chile excelled at doing so when they were working with Lillo. They were combative through central lanes, where their strikers and central defenders joined those in central midfield in applying the desired press – often in the attacking half. The close connections they offered during build-up phases, from the front to the back of their structure – and therefore as possession was lost – made that common.

Other teams have applied an interception-led counter-press, in which pressure is applied to the ball carrier to encourage errors – most commonly inaccurate passes. Teams who are physically inferior to their opponents, and therefore may struggle for the necessary strength required to directly dispossess an opponent, are suited to doing so. Lillo's press is often built on his team's midfield – secondary support comes from their attackers, because their defenders rarely join a press in the middle of the pitch – encouraging quicker transitions forward if regains are made after a counter-press.

By players prioritising blocking passing lines and interceptions instead of directly duelling, once possession is recovered their midfielders are immediately in a position to receive; through not being attached to a specific opponent, the ball can be retained and quickly progressed forwards without succumbing to counter-pressure. That potential flexibility, and the extent to which Lillo's approach is determined by the players at his disposal, is regardless built on a consistent philosophy that prioritises attacking possession and territory, and intense pressure.

Want to know more about football tactics and learn how to coach from the very best? Take a look at CV Academy here