ronald koeman

Barcelona, 2020-2021

It was a great former player, in Pep Guardiola, Barcelona turned to when appointing a new manager to transform them when last they were at such a low. In that respect, Ronald Koeman's arrival as the successor to Quique Setién gave them significant reason to be optimistic about their hopes of challenging Real Madrid, who with Zinedine Zidane were also succeeding under one of their greatest former players.

If Koeman was aware of the demands involved in playing for one of the world's biggest and most successful clubs, he had already proved himself capable of rebuilding a squad that has reached the end of its cycle. At Southampton, he oversaw the signing of Virgil van Dijk, among others, having arrived at the same time that the influential Adam Lallana, Dejan Lovren, Luke Shaw, Calum Chambers and Rickie Lambert were being sold, and he then inspired them to qualify for the Europa League. He left Barça before he was able to finish reshaping the team that was shorn of Lionel Messi, but not before overseeing the elevation of Pedri and Gavi – perhaps the leaders of their next great team – into significant figures for both country and club.

Playing style

Koeman has so far proved a particularly flexible manager whose approach is determined by the qualities of the players at his disposal. At Southampton he favoured a 4-3-3 formation that potentially evolved into a 4-2-3-1, depending on their opponents, and occasionally even experimented with a 3-4-1-2. His next position, at Everton, first involved a preference for both a 3-4-3 and a 3-5-2 – both systems featured wing-backs – and later a 4-3-3 with wide attackers that became a 4-2-3-1 in which the three supporting the lone striker remained in narrow positions.

With the Netherlands he worked with a calibre of player similar to that he inherited at Barça. He therefore mostly oversaw a more open and attacking 4-3-3, before relying on the use of three central defenders against the front threes of Portugal and Italy. More than any of the other teams he had coached, the Netherlands demonstrated the attacking football that most resemble the traditions valued at Barça.

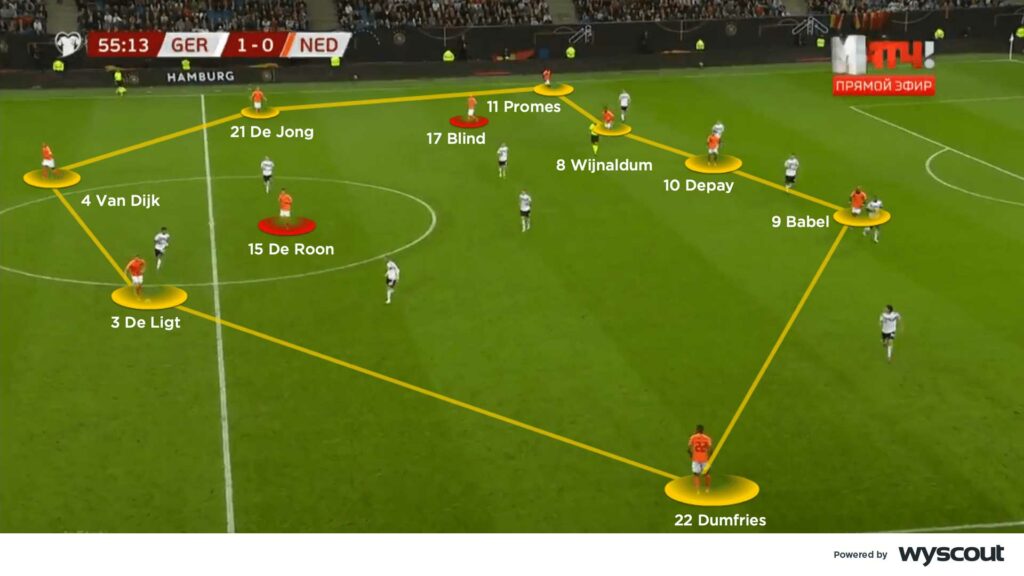

If Koeman‘s teams have rarely prioritised possession of the ball, the Netherlands – largely owing to the talented midfield that often featured De Jong and Donny van de Beek, and therefore had a fine sense of positioning and technical ability that meant that they could often dictate play – proved different. Their goalkeeper Jasper Cillessen contributed to their efforts to build possession, whether with the central defence formed by Van Dijk and Matthijs de Ligt, or De Jong from midfield.

Their midfield three was organised into a triangle that featured either a single (above) or a double pivot, depending on the nature of their opponents. A defensive midfielder regardless consistently had an influential role. The full-backs and wide forwards either side of them also rotated positions – Daley Blind and Quincy Promes did so particularly effectively – testing their opponents and contributing to their efforts to free up a passing option. When possession progressed beyond the defensive third, horizontal passes were rare. The ball was instead circulated at speed with the intention of generating positional imbalances within their opponents' structure, and spaces to advance into – often via triangles.

The Netherlands regularly encountered teams who resisted pressing in favour of holding their positions, so the in-possession central defender was regularly encouraged to carry the ball into midfield, to draw opponents and therefore create space. De Jong was also instructed to be consistently involved; his variety of pass was central to their fluid approach and providing those in wide positions with the time and space required to deliver crosses into the penalty area.

Particularly against those defending with a low block, Koeman instructed his team to prioritise the wide areas of the pitch, often by switching play. Towards the left, where De Jong drifted to support Blind and Promes (above), they offered significant potential; those efforts were complemented by those in the final third adopting positions between their opposing central defenders, to create space. Their wide forwards also attacked infield, or wider, depending on the circumstances – inviting the full-backs behind them to advance and ultimately creating more attacking depth.

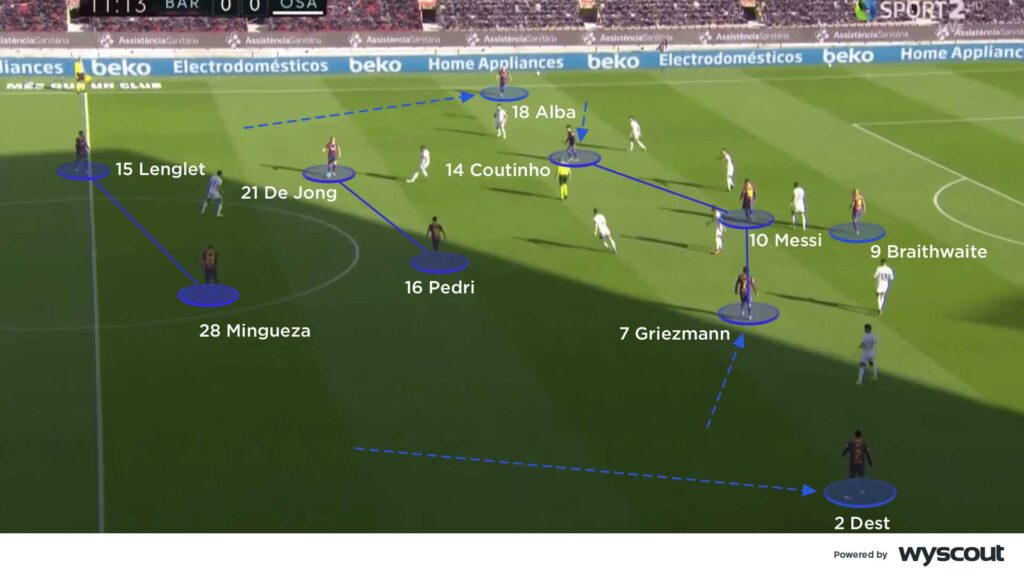

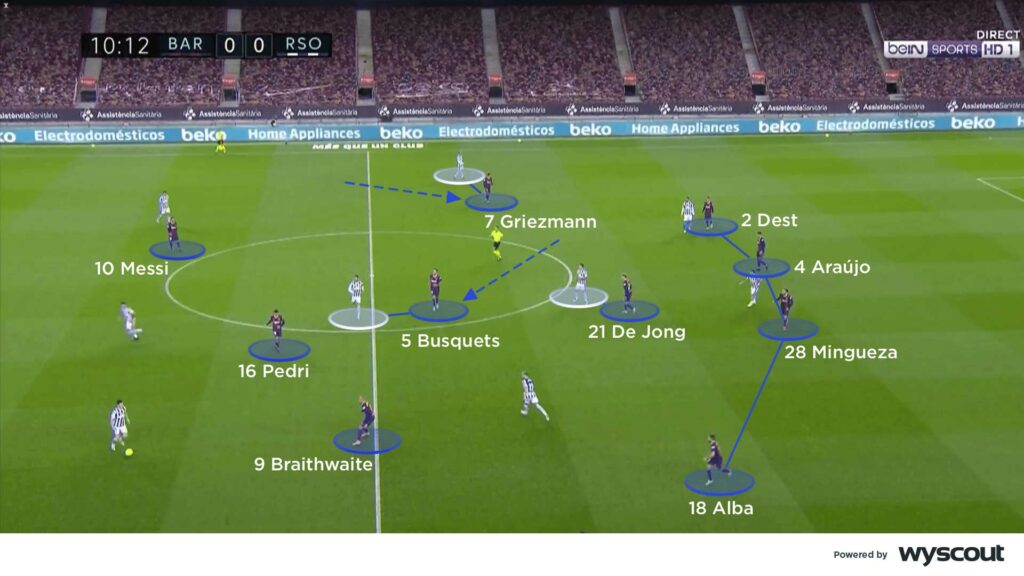

De Jong was given a similarly prominent role within the 4-2-3-1 with which Barça first appeared under Koeman (above). Partnered with Sergio Busquets at the base of their midfield, as at Ajax and with the Netherlands, he was instructed to withdraw into defence when their full-backs Jordi Alba, Sergi Roberto or Sergiño Dest advanced – that responsibility had long been Busquets' but, having reached his 30s, his decreasing mobility had made him a less effective single pivot.

With their full-backs providing Barça's width, Messi and Philippe Coutinho were encouraged to attack infield and to operate between the lines. Coutinho also drifted towards the left to link with the overlapping Alba, and Ansu Fati's penetrative runs, ensuring that there were times their shape resembled a 4-4-2 or 4-2-4 and featured Koeman's favoured narrow attackers. Injuries suffered by both Coutinho and Ansu, and some inconsistent results, then contributed to Koeman experimenting with Barça's traditional 4-3-3 and Busquets as their single pivot, before their relative lack of quality led to him favouring a back three (below).

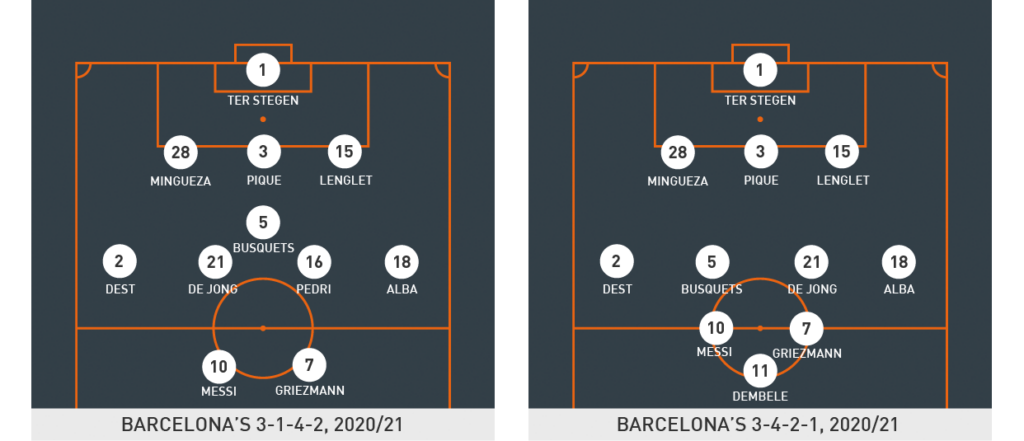

Their increased numbers in midfield in either their 3-1-4-2 or 3-4-2-1 gave Busquets additional passing options. Overall – via De Jong, Pedri and Ilaix Moriba – increased energy and creativity between the lines, and more effective combinations with their wing-backs' attacking runs, also existed.

In the attacking half Messi remained more central for lengthier periods and, unlike during most of his club career, was given increased freedom to drift towards the left, and to contribute by progressing possession from deeper positions and into the final third by assisting the assist. Antoine Griezmann benefitted from a more central role, where his instinctive movements supported Messi's play, after previously being asked to cut infield from wider positions.

Defending and pressing

Koeman most commonly organises his teams to have a defensive approach led by their method of attack, whether that be a 4-3-3, a 4-2-3-1 or an alternative, and to defend with minimal space between the lines. The height of their defensive block is also determined by their opponents’ attacking approach; if they favour a passing game that starts from their goalkeeper, a high press is applied and three advanced players prioritise closing their passing lanes. That coordinated press, discouraging the goalkeeper from playing to the central defenders or defensive midfielder in front of him, starts as soon as the ball begins to move, and also features adjustments that close the relevant spaces, and ultimately limits connections between defence and midfield.

It is when the opponent succeeds in advancing that that press is then adjusted, and a compact shape is adopted in midfield. If using a mid-block, the in-possession player and his nearest passing option is pressured, encouraging him to instead play into areas in which the pressing team is likelier to recover the ball. That desire to retain a compact shape even involves their wide players drifting infield to defend (above).

When working with an inferior quality of player at Everton, and therefore a team less capable of defending with the ball, Koeman's favoured defensive strategy was built on either a 5-3-2 or a 3-4-3. Both shapes also involved them defending from close to their penalty area. The wing-backs in both systems were particularly important. In their 5-3-2 they withdrew into their defensive line while they were defending, and advanced to leave a back three if required further forwards. Their shape therefore often even involved three central defenders, two full-backs, and three defensive midfielders behind the two attackers contributing to the defensive efforts behind them.

Barça's typically strong grasp of possession meant their defensive approach focusing on pressuring high up the pitch and negating counters, and therefore ensured that a mid-block was used more sparingly. From their 4-2-3-1 their full-backs and a defensive midfielder advanced to contribute when they were defending from further forwards, ensuring that they had the numbers required to counter-press and force mistakes or ensure regains. There also existed a focus on restricting the ball to central areas via that counter-press – ensuring it remained close to where they offered numbers, and that their full-backs had time to recover into their defensive positions and support their single pivot from in front of their two central defenders.

On the occasions they adopted a mid-block, their central midfielders, led by their double pivot, focused on man-marking and aggressively tracking their opponents' movements, which often involved vacating those central spaces and risking opponents rotating into them and receiving possession. Barça's wide forwards were therefore also often forced to support and defend from slightly deeper, and their full-backs to adopt narrower positions, undermining their attacking potential during moments of transition.

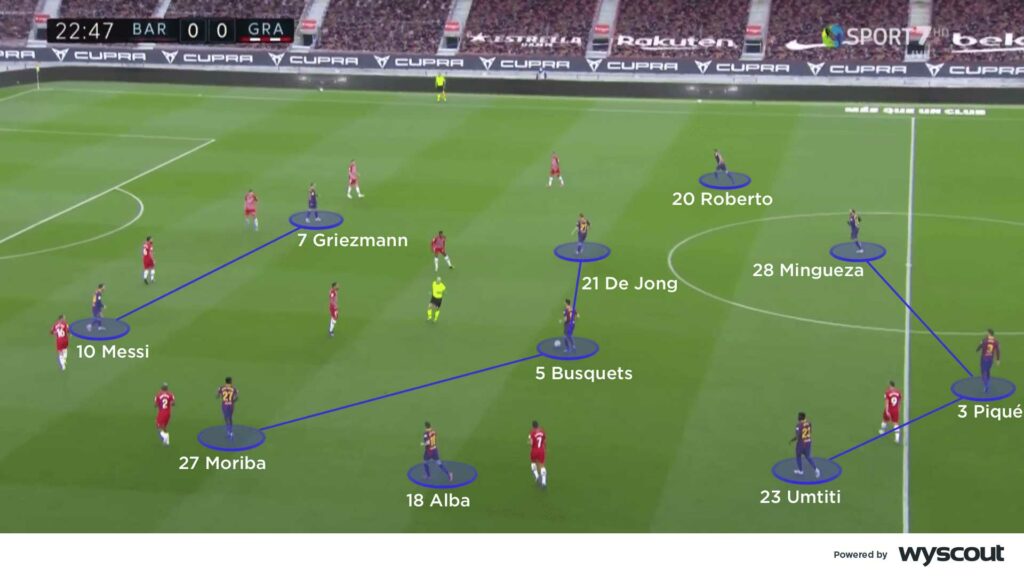

From the point Koeman introduced their back three, their counter-press focused on making quick regains via the numbers they offered through the centre of the pitch, where they consistently had three central midfielders and Messi, who withdrew into deeper territory as they built play. Their wider central defenders also pressed with aggression in following attackers withdrawing into deeper positions, or in pressing into midfield in the knowledge that two central defenders remained behind them and that the athleticism of Alba and Dest could contribute to the formation of a back five (above).

The presence of three natural central defenders, instead of two complemented by a midfielder withdrawing into defence, strengthened Barça's ability to defend against counters and their defensive presence against opposing attacks. In front of them, Busquets and De Jong effectively combined to screen forward passes, where previously they were responsible for defending larger spaces. Their wing-backs moved to form a back five, and two attacking players pressed towards the wide areas after initially screening the centre of the pitch; their front line also attempted to cover central access and to prevent opponents from building possession via their deepest-positioned midfielder. When one of Barça's defensive midfielders advanced, a central defender replaced him in their double pivot and, because their wing-backs had retreated, a back four remained in place to defend against direct play and passes in behind.