Dean Smith

Charlotte FC, 2023-

Profile

Since starting out as a manager in January 2011, Dean Smith has worked consistently for more than a decade. Having moved directly from Walsall to Brentford, and then from Brentford to Aston Villa, one might have expected him to take a break from the game when he was sacked by his boyhood club in November 2021. Smith had other ideas, though, and just eight days after leaving Villa, he became manager of Norwich City. At the time of that appointment, Norwich were rooted to the bottom of the Premier League, with just five points from the 11 games Daniel Farke had been in charge for in 2021/22.

However, Smith was excited to get to work and intent on turning the season around. “It’s great to get straight back in [to football] with a club that are determined to be progressive,” Smith said. “I’ve always worked to improve and develop players – with that obviously comes improved performances.”

He was unable to save Norwich from relegation, however, and left the club in December 2022. This was followed by a short spell at Leicester City, taking over with eight games of the 2022/23 Premier League season left to play and the Foxes fighting relegation. Smith was again unable to turn the tide sufficiently, and left Leicester that summer. His next job would be as manager of MLS club Charlotte FC.

Playing style

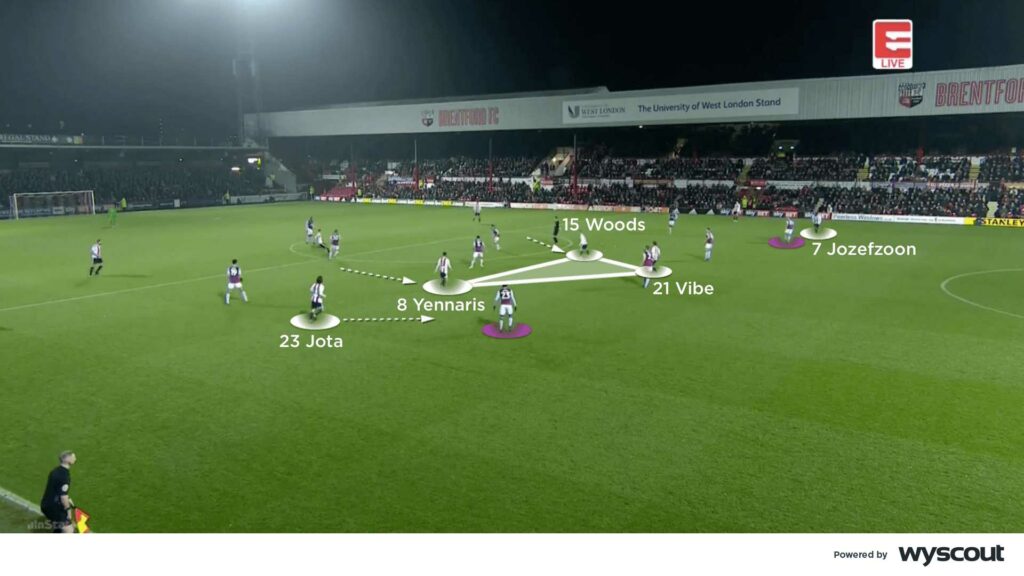

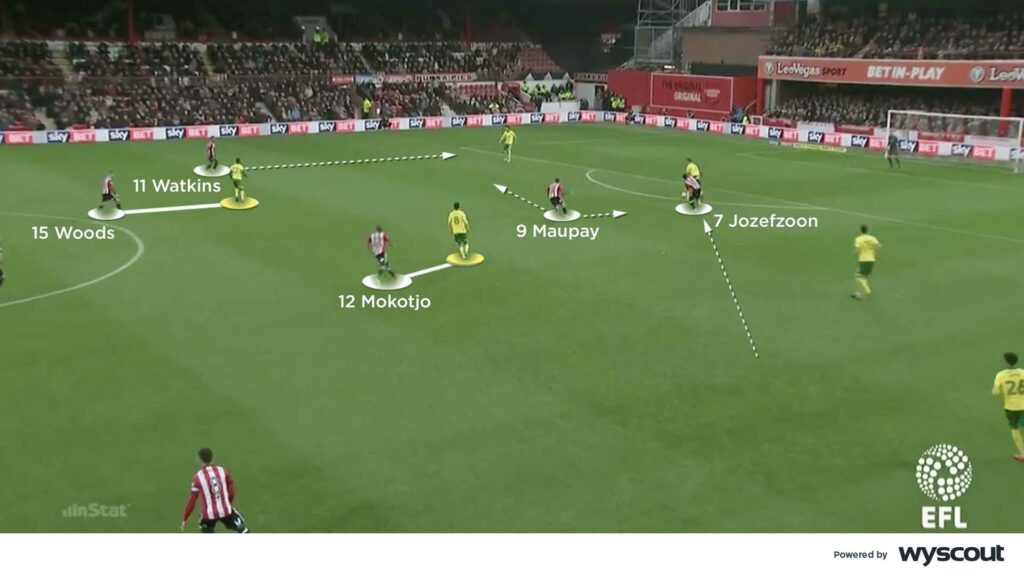

In addition to the odd brief experiment with a back three, Brentford used a proactive, attacking 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1 in the early days of Smith’s tenure. With this shape, they were the fourth highest scorers in the Championship in 2016/17. They employed either a single or double pivot; the full-backs provided the width in the build-up phase, although they rarely overlapped in attack. The wide forwards retained the team’s width, and their attacking central midfielder or midfielders advanced particularly high (below).

Brentford kept the ball well under Smith, and opponents often dropped into a low block against them. To break these blocks down, they regularly used rotations in which their attacking midfielders overlapped around the outside of their wide forwards. Ollie Watkins was particularly influential when drifting in from a wide starting position on the left to operate as a secondary striker in support of Neil Maupay.

Smith also mostly used a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1 at Aston Villa. While Brentford often created through the centre of the pitch, Smith’s Villa put more crosses into the box, having attacked around the outside of their opponents. Jack Grealish and John McGinn were their two most prolific dribblers in 2018/19; they consistently offered forward runs from central starting positions and combined with the wide forwards.

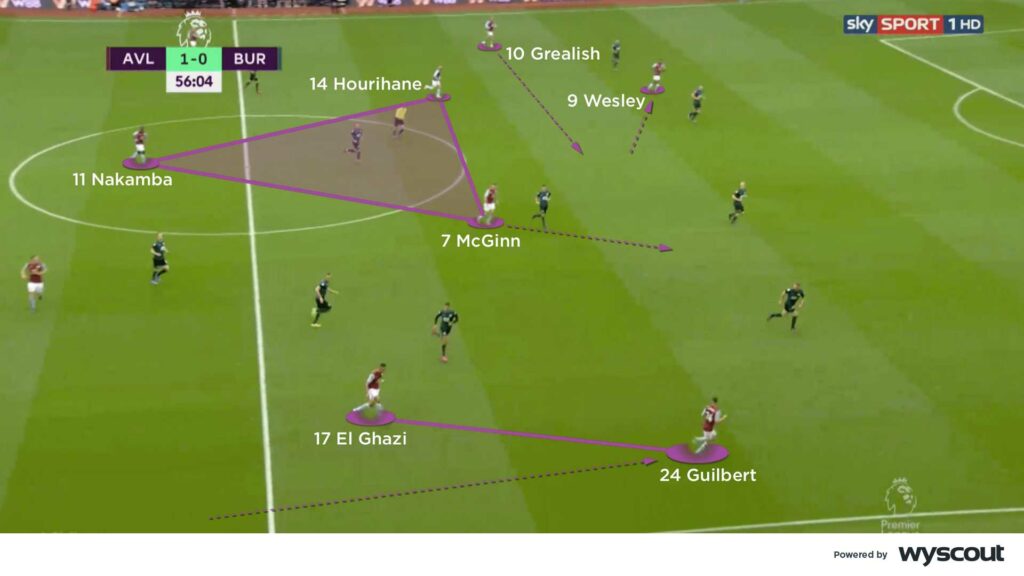

Crossing play remained a prominent feature of Villa’s game after they returned to the Premier League in 2019/20. In that season, they attempted the fifth most crosses in the league – but they evolved, with many crosses coming from advancing full-backs Ahmed Elmohamady, Frédéric Guilbert and Matt Targett.

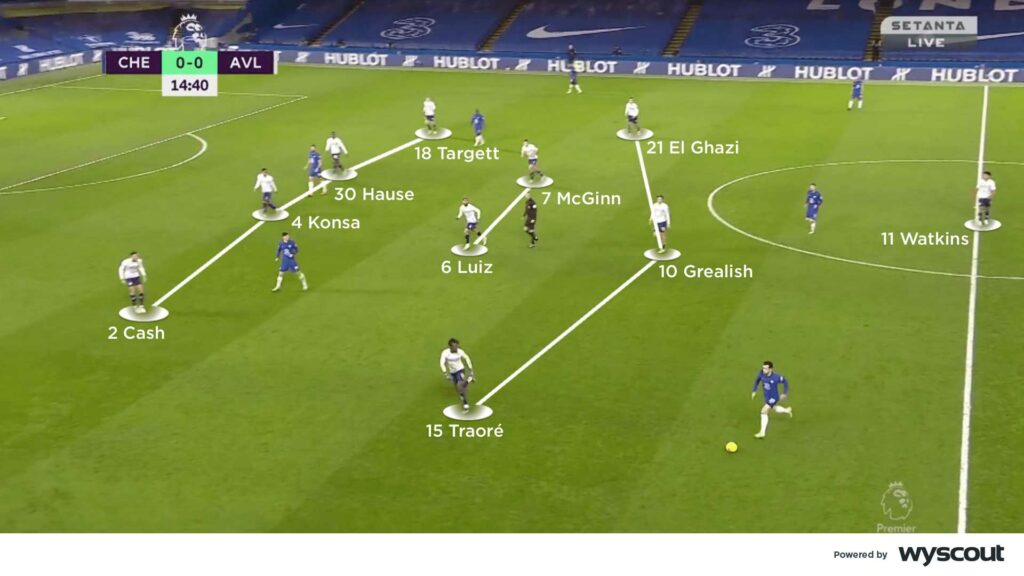

Key man Grealish was given a new starting position wide on the left (below), but he constantly moved off the flank, while Targett overlapped around the outside from left-back. On the right, their width was more consistently held by the right-sided forward, though there were occasions when the right-back got into a position to cross and the right-sided forward attacked the box. On the left, Grealish was more likely to lurk outside the area when Targett got forward.

Smith’s Villa developed further in 2020/21. Their attacks became more direct and they demonstrated improved game-management, too. Matty Cash, recruited in the summer of 2020, regularly provided crosses from right-back. Watkins, who Smith signed from Brentford, improved the team with his ability to receive on the move and his unselfish runs – both of which helped Villa counter-attack at pace. The on-loan Ross Barkley added further thrust from midfield, and proved well-suited to a box-to-box role.

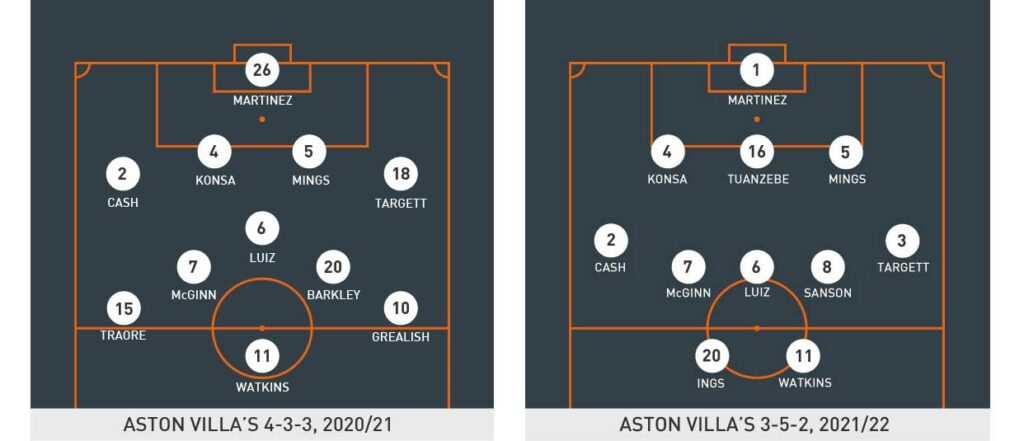

Following Grealish’s departure to Manchester City, Smith had to rethink his team’s attacking strategy. Almost all of Villa’s attacking play had gone through Grealish at some stage, and there was no way of Smith finding a like-for-like replacement.

He signed Danny Ings, and swiftly set about finding a formation that accommodated two centre-forwards. That would keep Watkins central, and not move him back out to the left, where he had played for Brentford under Smith. To do this while retaining the central midfield three he prefers, Smith switched to a back three.

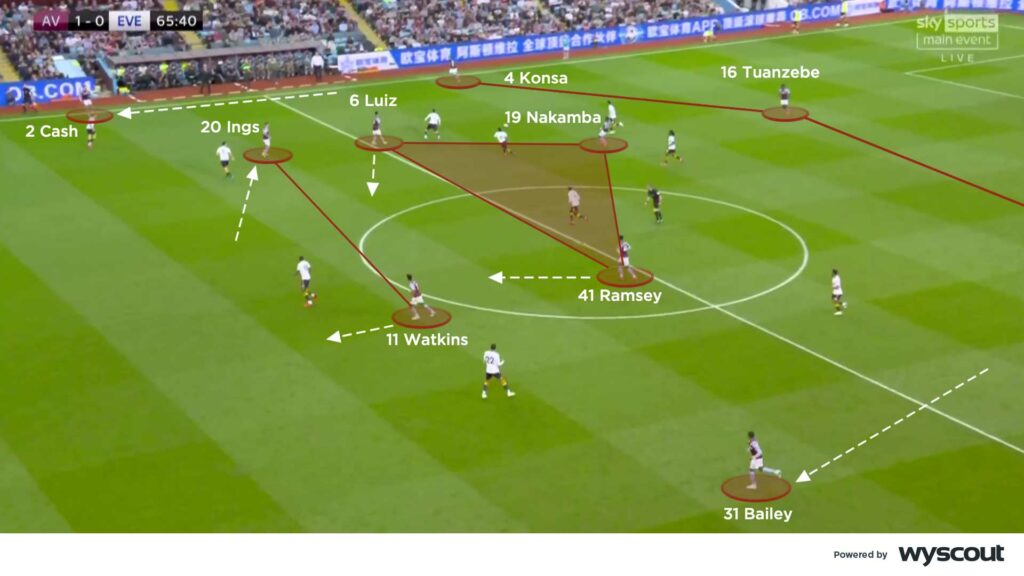

Without Grealish to carry the ball forwards on the left, Villa became a more balanced side. Cash’s influence grew on the right as an aggressive wing-back, while Targett or Leon Bailey maintained the threat from the left, and both wing-backs attacked simultaneously (above). One of Ings or Watkins then moved into the inside channel to create overloads out wide, or to create space centrally for Cash to attack. The other centre-forward would look to threaten in behind, creating space for Villa’s number eights to push into. This resulted in similar midfield movements to those seen under Smith at Brentford, although at Villa it was often the wing-backs who got high enough to attack the penalty area rather than the central midfielders.

Defending and pressing

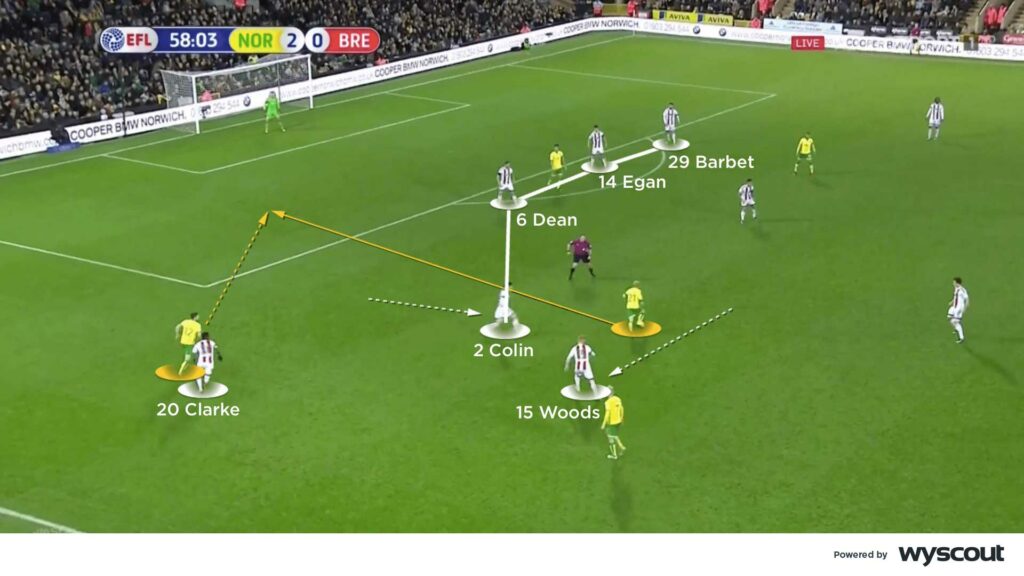

Smith’s Brentford often left themselves far too exposed at the back. Their attacking approach led to them conceding too many chances. In 2016/17, they conceded more goals than three of the Championship’s bottom six teams. When Brentford's wide forwards moved infield, their attacking midfielders advanced. As a result, their full-backs were often left isolated when opponents counter-attacked.

The following season, Smith introduced a more aggressive high press (above). This succeeded in that Brentford recorded the third most regains in the final third in the Championship in 2017/18, and their defensive record improved markedly. Smith’s attacking midfielders advanced to press alongside their narrow attack, and their back four stayed compact. Watkins and Maupay, who formed the first line of the press, added mobility and energy in the final third. They pressed intelligently and worked willingly, with the aim of forcing their opponents into areas where they were most likely to concede possession. They often pressed from behind, in order to direct their opponents into a crowded midfield.

After promotion to the Premier League, Smith’s Aston Villa mostly defended with mid and low blocks. But, as was the case with Brentford (above), they were vulnerable if opponents built with width as a result of the attacking licence he gave his full-backs.

Even if their starting formation was a 4-3-3, they regularly defended with a double pivot through McGinn or Hourihane dropping alongside the influential Douglas Luiz (below). With time, Villa defended with a slightly higher defensive line, closer to the double pivot, to make the team more compact. The distance between Villa's midfield and front three also reduced as the team became more used to Smith’s approach. Opponents consistently found less space between the lines.

Villa struggled to maintain the same defensive resilience following Villa’s switch to a back three. Smith encouraged his wing-backs to join attacks, so opponents had plenty of joy counter-attacking into the spaces they vacated. The centre-backs struggled to get across quickly enough to delay their opponent and allow teammates to make recovery runs. As a unit, the Villa defence proved ineffective at moving across to try and lock play near the touchline.

Equally, when they had dropped into a deeper 5-3-2 block, their midfield three struggled against switches of play. Their wide centre-backs had to move out to support the isolated wing-back. This led to the defence being exposed all too regularly.