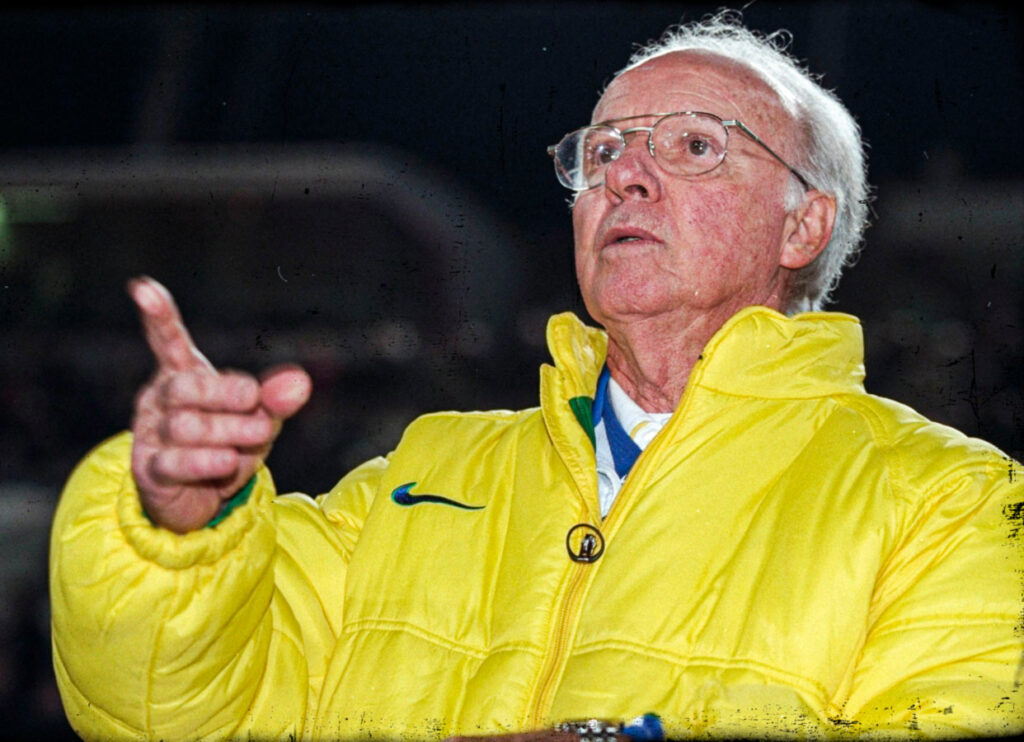

MArio zagallo

Brazil, 1967-1968, 1970-1974 & 1994-1998

No country on earth enjoys quite the same relationship with football as Brazil. They are the only nation to have appeared at every World Cup since the inaugural tournament in 1930. The only team to have lifted the trophy five times. And they boast a footballing culture like no other, built on an entertaining, attacking style and generations of supreme footballers. Pelé, Garrincha, Tostão, Jairzinho, Zico, Socrates and, more recently, Romario, Ronaldo and Ronaldinho.

There is one name missing from that list, however. A man who, while not achieving global renown as a player, must figure in the pantheon of Brazilian football greats. That man is Mário Zagallo.

Nicknamed ‘The Wolf’ – his full name includes the surname ‘Lobo’, the Portuguese for wolf – Zagallo was a diminutive left-winger who shone for Flamengo and Botafogo in a playing career that ran from 1951 to 1965. He was a key player in the Brazil teams that won their first and second World Cups – in Sweden in 1958 (below), and Chile in 1962. He started both finals, scoring the team’s fourth goal in a 5-2 win over the hosts in the former.

Despite his two World Cup winners’ medals, however, it is as a coach that Zagallo has built his legend. Specifically, as head coach of what many judges still consider the greatest international team of them all – the Brazil team that won the 1970 World Cup.

The team qualified for the tournament, to be held in Mexico, under the guidance of João Saldanha. Saldanha was a journalist as well as a coach, and had criticised the military regime that then ruled Brazil. On the back of a tense relationship with the influential Pelé and some poor friendly results, he was fired in the build-up to the World Cup. Zagallo, then Botafogo manager and still only 38 years old, was hired.

What followed has gone down in history, as Brazil became the first three-time World Cup winners. They produced a succession of displays that captivated the world before destroying fellow two-time champions Italy in the final.

Zagallo led the team to the next World Cup, in West Germany in 1974. There, they were denied a place in the final by another iconic team – the Netherlands of Rinus Michels and Johan Cruyff. He would later return as assistant to Carlos Alberto Parreira ahead of the 1994 World Cup in the United States. The pair duly led Brazil to their fourth World Cup title.

Returning as head coach for France ’98, Zagallo found himself in yet another World Cup final. There, the hosts denied the Seleção in a final notable for the mystery surrounding star striker Ronaldo’s participation before kick-off. Four years later, and now in his 70s, Zagallo went to the 2002 World Cup, in Japan and South Korea, as a special adviser to the Brazilian technical staff.

His involvement with the team that secured a record fifth World Cup established him as the single unifying thread tying all five victories together across almost 50 years of football history. That is quite some legacy for a man who turned 90 in August 2021.

Style of play

Two legendary Hungarian coaches played a central part in the formative years of football in Brazil. Dori Kürschner had won domestic titles with Nürnberg in Germany and Grasshoppers in Switzerland before moving to Brazil. There, in the late 1930s, he introduced the W-M system Herbert Chapman had first developed in the 1920s.

Two decades later, Bela Guttman took a Honved team featuring Ferenc Puskás, Sándor Kocsis and Zoltán Czibor on a five-game tour of Brazil. Guttman stayed on to take charge of São Paulo, with whom he utilised his preferred 4-2-4 formation. It is no coincidence that a Brazil team featuring Zagallo won the 1958 World Cup using the same shape.

The principle underpinning both approaches was of a structured unit in which the best players could thrive and succeed. In that regard, Zagallo the coach was their natural heir.

His belief was that individual talent would always excel, as long as it was supported by order and teamwork. A calm and conciliatory character, he convinced a team full of stars to assume certain responsibilities on the pitch.

“I want discipline and order, will and self-sacrifice from all of you,” he reportedly said in his first meeting with members of the team led by Pelé (above). “When I was a player, I was criticised a lot for my style, but I kept on fighting. That is what I want today from every member of the Brazilian national team. In today’s football, everyone has to fight, regardless of your role.”

No matter who those players were to be, Zagallo’s teams had a number of very definite features. A back line of four was constant, with full-backs pushed forward to attack almost as wingers. The attacking midfielders in front of them moved from out to in, seeking goalscoring positions.

The principle of pass and move was at the heart of everything. No player was allowed to stand still. Every player was expected to constantly look for positions in which they could be a passing option for the ball-carrier. When they received the ball, their job was to look immediately for a teammate before once again moving to support. It was a simple premise that became the central pillar of Zagallo’s two Brazil teams.

Offensive phase

1970: The false 4-3-3

Zagallo believed that his best players should always be on the pitch. That sometimes meant having to convince them to play in unfamiliar roles. In the 1970 Brazil team, that applied most of all to Piazza.

Piazza was a central midfielder who had been called up by Saldanha to play in his preferred position. Once Zagallo took over, however, he was moved back to play as a central defender. The idea was that Piazza's ability on the ball would improve the team’s build-up play from deep. From there, he could link with the full-backs, Carlos Alberto and Everaldo, and the team’s new central midfielder, Clodoaldo.

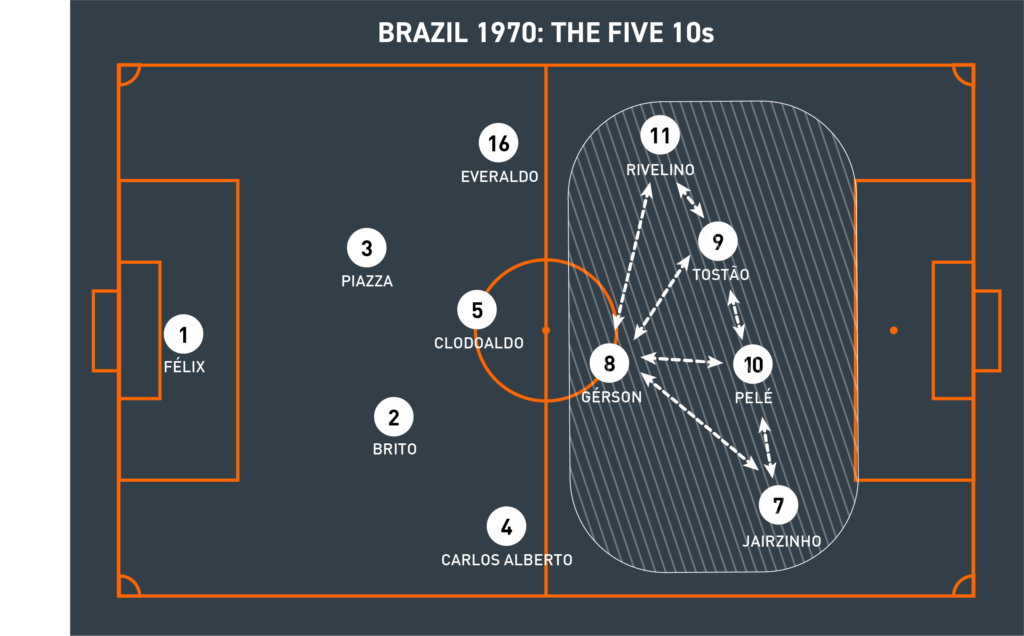

Ahead of Clodoaldo, the team's single pivot, Zagallo selected a group of five attacking players who constantly interchanged positions. Individually, Gerson, Rivelino, Jairzinho, Tostão and, of course, Pelé were all star players. As a collective, Zagallo used his so-called ‘Five 10s’ (below) in a dynamic, fluid attacking structure. Opposition defences had never seen anything quite like it.

The result was something resembling a false 4-3-3 formation, in which the back four and Clodoaldo offered positional structure. The front five moved freely ahead of them, adopting different positions depending on the game situation and opposition set-up.

The build-up started with Piazza, who linked with Clodoaldo or one of the full-backs – mostly Carlos Alberto on the right. Further forward, the team looked for its chief playmaker and often the deepest of the front five: Gérson.

Gérson was the main creative influence in Zagallo’s team. He was the primary source of short link-up play, whether with Clodoaldo or in support of the advancing full-backs. Beyond that, his passing range meant he could also look longer to those further forward. As one of the five 10s, he also looked to make late runs into attacking areas. That could be to combine and create chances for a teammate, or to take a shot on goal himself.

The full-backs provided attacking width, but also built partnerships with the attackers closest to them. This enabled Zagallo’s team to exploit two of their greatest offensive assets: the front five’s mid-range shooting, and Pelé’s ability in the air. The most iconic of the team’s five number 10s, Pelé was brilliant at attacking spaces on the run. He also had a prodigious leap and powerful header. When the full-backs got forward and played in crosses, Pelé was a constant threat to opposing defences.

Every one of the front five scored at least one goal in Brazil’s victorious run to the 1970 title. The team’s goalscoring star, however, was Jairzinho. He netted seven times across the tournament, most commonly from a starting position on the right flank. In doing so, he became the first player to score in every game of a men's World Cup, up to and including the final. He remains the only man to have done so.

The most famous goal scored by this iconic team, however, came from right-back and captain, Carlos Alberto, in the final. It is the fourth and final strike of Brazil’s 4-1 mauling of an exhausted Italy. The move begins with patient possession, followed by swift and well-timed forward progress. A quick and efficient switch from one flank to another results in a stunning low finish from an advancing full-back. In many ways, it is the epitome of everything Zagallo wanted his team to be.

1998: The 4-2-2-2

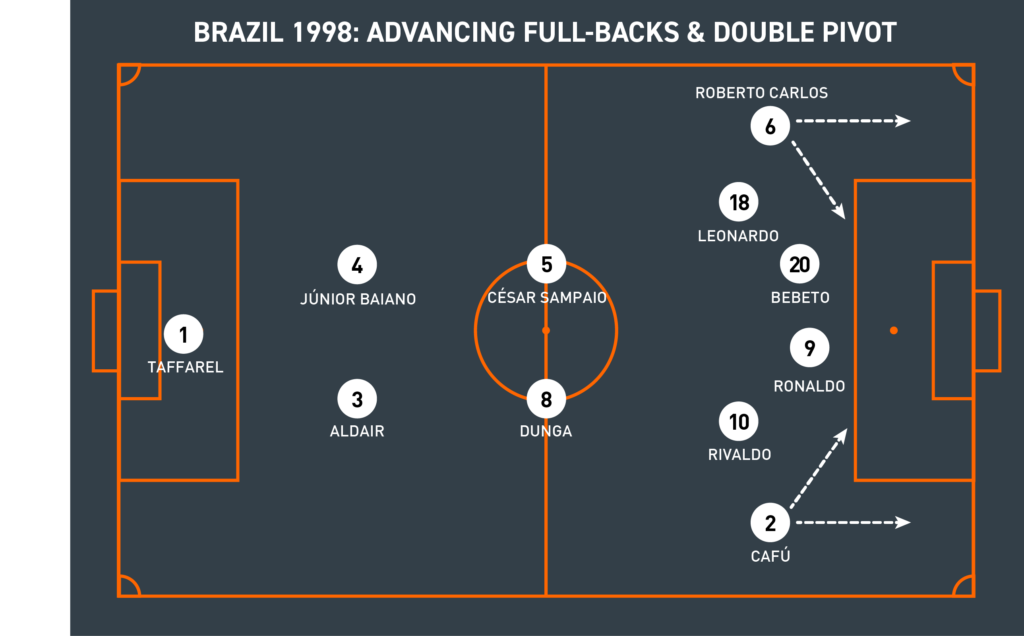

The next-generation Brazil team Zagallo brought to the 1998 World Cup in France utilised a defined 4-2-2-2 formation. Advancing full-backs, by now Roberto Carlos and Cafú, played just as important a role as they had 28 years earlier. Unlike in 1970, however, Zagallo now turned to a double pivot in midfield. Dunga and César Sampaio were to provide defensive solidity in front of potentially exposed centre-backs.

Also unlike the 1970 team, Zagallo’s 1998 vintage started the build-up from the goalkeeper. Claudio Taffarel’s ability with the ball at his feet allowed him to find either centre-back – Aldair or Júnior Baiano – or one of the central midfielders with the first pass. If the opposition pressed high, he had the passing range to look further forward – to the forwards, attacking midfielders or even the advanced full-backs.

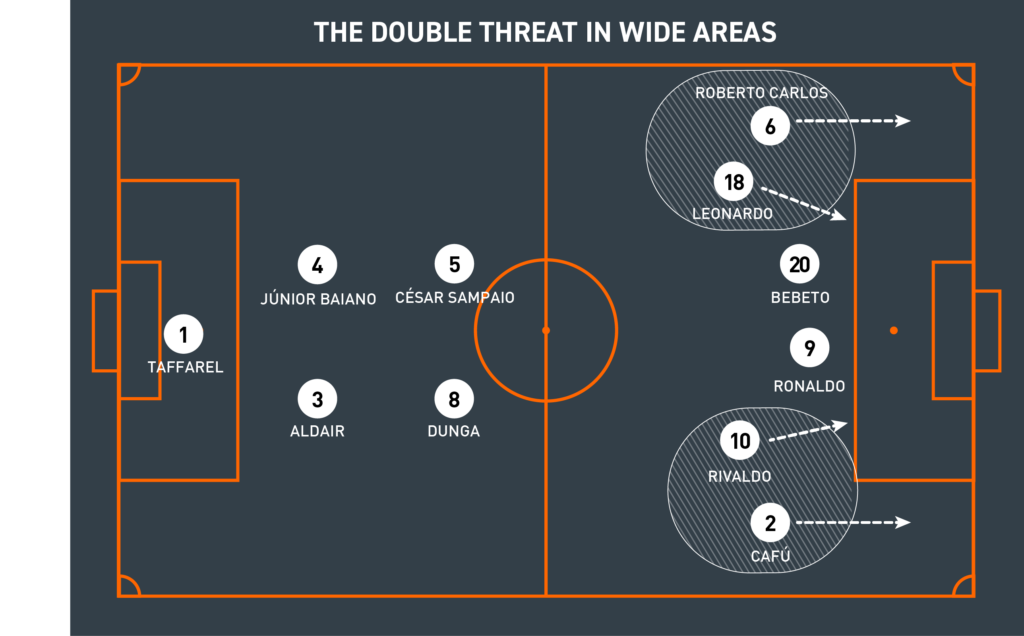

Relying on the full-backs to offer attacking width in this way gave Zagallo the freedom to push the team’s two attacking midfielders into more central and potentially threatening areas.

Both Leonardo and Rivaldo were left-footers who liked drifting inside, but they offered the team very different qualities. Rivaldo offered the greater attacking threat, cutting in from the right on his favoured left side to play penetrating passes or unleash his trademark powerful shots on goal. Leonardo was a more versatile player, comfortable in different areas of the pitch. His background as a full-back gave the team greater understanding of wide combinations in advanced areas.

In this version of Brazil, Zagallo placed a great emphasis on the partnerships between the attacking midfielders and full-backs. Indeed, the latter should offer as much attacking threat as the former (above), if not more. Cafú was a superb crosser from wide areas, but also an excellent passer who could combine inside if Rivaldo held his width on the right. On the opposite flank, Roberto Carlos was an equally talented crosser of the ball. He also liked to make diagonal runs inside and, famously, unleash shots with his piledriver of a left foot.

Ahead of them, Zagallo played with two strikers. Bebeto, retained from the World Cup-winning team of 1994, was a busy forward constantly looking to find space away from opposition centre-backs. Ronaldo (below) had long been touted as a potential star but was still only 21. An imposing, athletic striker, his play without the ball was as important as his dribbling, drag-flicks and finishing with it.

His ability to drop away from play, pulling defenders out of position and creating space for runners around him, enabled the team to rely on more than just his goals. Ronaldo himself scored four goals in the tournament, but Bebeto, Rivaldo and even César Sampaio – the more attack-minded of the double pivot – all registered three goals each. Only hosts France, who defeated the Seleção 3-0 in the final, scored more than Brazil in the tournament.

Defensive phase

1970: The risky high line

The 1970 World Cup took place in Mexico in June, so was always going to be played in very high temperatures. Zagallo and the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) knew this, so decided the team should arrive well in advance so they could get used to the conditions.

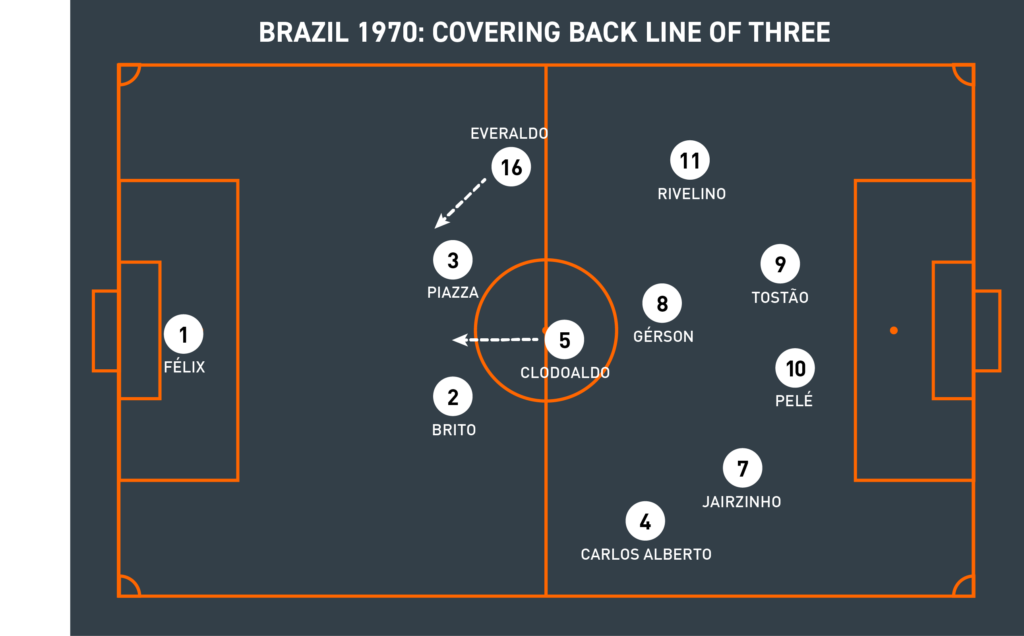

Zagallo also wanted to compress the pitch as much as possible in the defensive phase. When they progressed into the opponents’ half, a covering back line of three – both centre-backs and usually Everaldo, the less attacking full-back would push up as high as the halfway line. Clodoaldo would generally sit just in front of them.

That left a lot of space in behind on transition. For all their offensive prowess, this was a team that conceded both chances and goals. The seven goals they conceded in six games is more than any subsequent World Cup winners have conceded in the 12 tournaments since 1970.

When facing more structured attacks by their opponents, Brazil set up with a much lower block and dropped into a defensive shape more resembling a 4-4-1-1. The back four would start a few metres from the penalty area, with Gérson dropping alongside Clodoaldo into a midfield two ahead of them. Rivelino and Jairzinho would defend the wide areas, leaving Tostão as the attacking pivot and Pelé ahead of him. When they then won the ball back, Gérson was the player to whom they looked. A fine technician, he was capable of launching a quick counter-attack or holding possession while the team reorganised into its offensive shape.

Zagallo had built a team to defend with the ball, however. He knew that the Mexican heat would make it almost impossible for teams to sustain high-pressing tactics against them. Yes, they played with a high line that gave opponents a chance – but, in the end, the effort required to win possession back against this team in that heat would ultimately cost opponents across 90 minutes. And so it proved.

1998: Central solidity

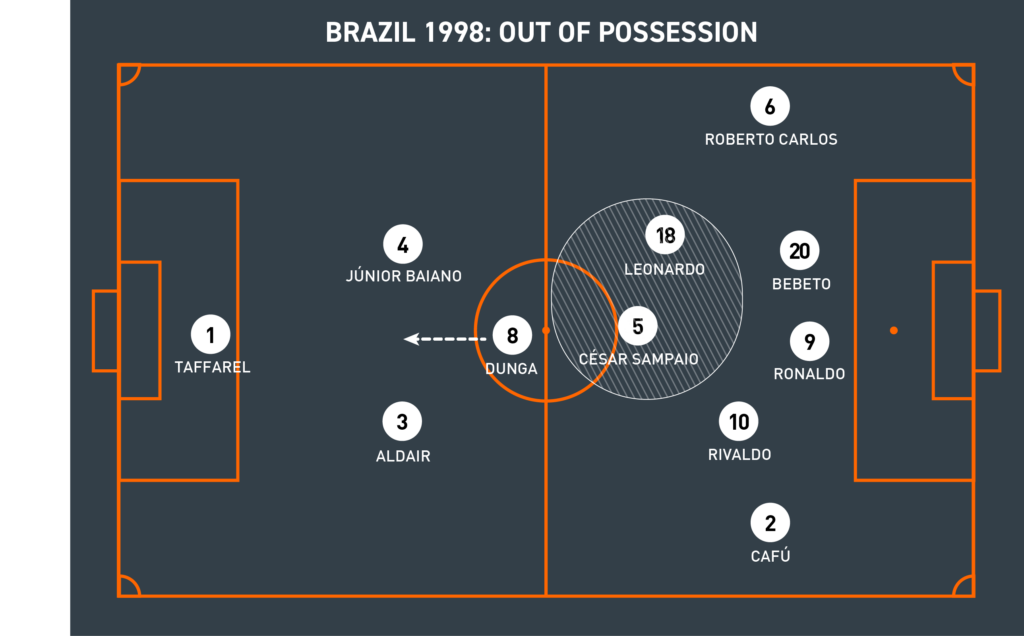

There was a more developed defensive structure to the Brazil team Zagallo led at France ’98. Despite his commitment to attacking full-backs, the double pivot in midfield served to provide the team with a sounder defensive base.

Against more organised attacks, the team would drop, as the 1970 vintage did, into a 4-4-1-1 shape. Here, Rivaldo would take up a position on the right side of the midfield. If the opposition didn’t commit numbers forward, however, he remained higher, offering an effective counter-attacking option in support of Ronaldo and Bebeto.

When the opposition regained the ball, Leonardo and César Sampaio – usually the higher of the two central midfielders – supported the forwards in initiating the counter-press (below). Dunga, the deeper-lying of the double pivot, maintained his position in front of the centre-backs. The captain was an intelligent on-field tactician and superb communicator who could protect his defenders, break up play and organise his teammates in the face of opposition attacks.

Opponents still looked to counter as much as possible in wide areas, in the vast spaces left by the rampaging full-backs Roberto Carlos and Cafú. Zagallo’s desire to get as many numbers forward as possible, and build his team around technically strong, attack-minded players, would always lead to a certain amount of defensive vulnerability. Brazil kept only one clean sheet at the 1998 World Cup – against Morocco, in the group stages – and conceded 10 goals across the whole tournament. No team in France that summer conceded more.

That, though, is part of Zagallo’s enduring legacy. As a coach, his first commitment was to attacking football. As such, he looked to build structures that meant he could get his most talented players on the same pitch at the same time. The result, across two World Cups almost three decades apart, was 33 goals in 13 games, two World Cup finals and one victory. For that, his place in football legend is assured.

To learn more from the professional coaches of The Coaches’ Voice, visit CV Academy