rafael benitez

Everton 2021-2022

Rafa Benítez is perhaps the only elite manager whose most recent positions have left him unable to compete among European football's finest. When he left Newcastle United for Dalian Yifang of the Chinese Super League he departed one club content at preserving its Premier League status for another in a developing division, making it little surprise the ambitions of Everton – who recruited him to succeed Carlo Ancelotti, as once did Real Madrid – tempted him back to England.

It was in the early noughties when Benítez established himself as a manager of potentially the highest calibre while twice inspiring Valencia to the Liga title, before he then left for Liverpool, who he led to the unlikeliest of Champions League triumphs. In between periods at Inter Milan and Napoli he oversaw Chelsea winning the Europa League, and briefly worked at Real before providing Newcastle with the stability they needed to become re-established in the Premier League. For all of his success and the years spent at some of Europe's leading clubs, however, he remains a relatively divisive, and often under-appreciated, figure in what might otherwise be his defining years in football – as his six months at Everton again showed. "Benítez must be among the top 10 methodical trainers," said Diego Alonso, his former player at Valencia. "Rafa Benítez is a genius. I was lucky to work with him and I learned a lot."

Playing style

Benítez favours, above all else, preparing his players to apply his preferred approach for the coming fixture, and in significant depth. The central midfielders in his teams are often an extension of his management, and the most important figures in maintaining the shape and approach he is demanding. At Valencia, David Albelda and Rubén Baraja were given that responsibility; at Liverpool it was Steven Gerrard, Xabi Alonso and Dietmar Hamann or Javier Mascherano; at Inter he trusted Esteban Cambiasso and Wesley Sneijder, and at Chelsea it was Ramires and Frank Lampard.

He instructs his players to attack quickly and directly towards goal after regains, and to vary whether they attack through the inside channels or with width. Although he wants those attacks to be direct, they are built in a methodical and organised way that involves a consideration of who will challenge for first balls, and therefore where others will be positioned to win second balls further forwards.

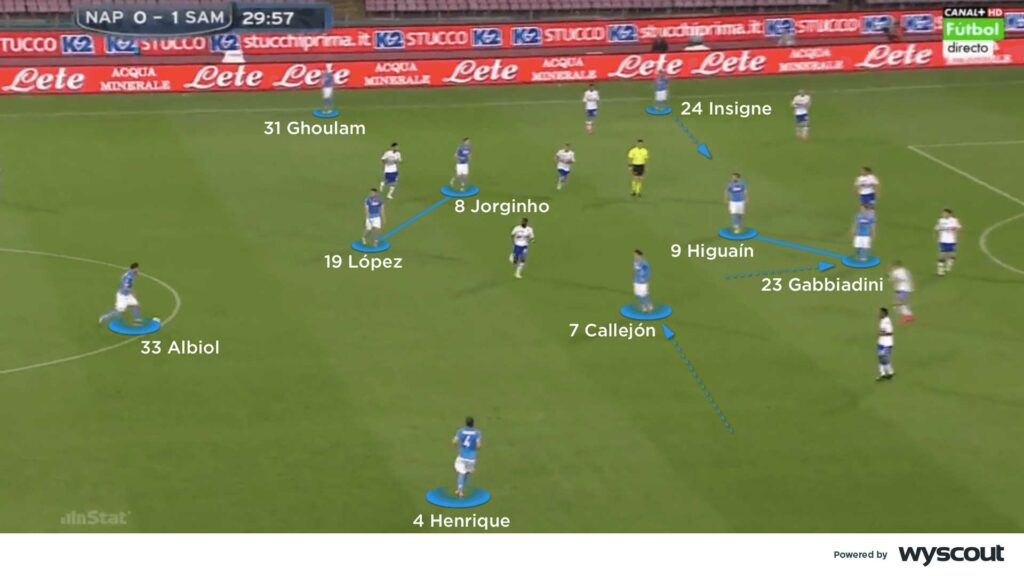

At Napoli, Benítez often used a 4-2-3-1 built towards supporting a lone striker with goalscoring, wide forwards who attacked infield (above). Dries Mertens, Lorenzo Insigne, and José Callejón frequently cut infield to shoot across goal; Gonzalo Higuaín started in an advanced position to create space for Marek Hamsik, or for Manolo Gabbiadini’s delayed forward runs, before withdrawing into a deeper position once they had progressed into the final third.

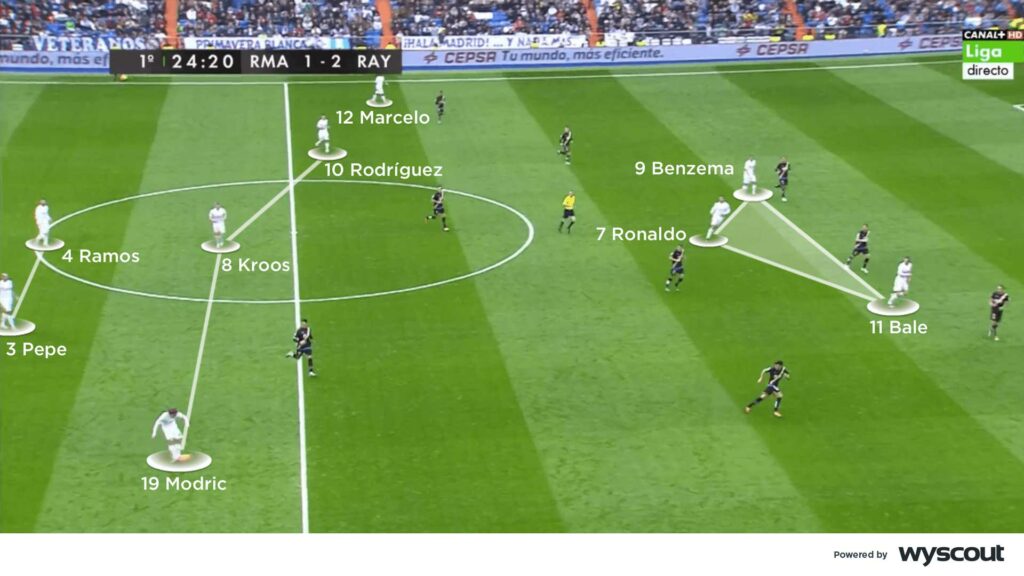

In addition to a similar 4-2-3-1, at Real he also oversaw a 4-3-3 in which a defined number nine and 10 were replaced by a front three that would adopt narrow positions (below) and rotate before racing to pursue balls over or through opposing defences or to attack crosses from wider positions. Cristiano Ronaldo and Gareth Bale were as suited to attacking those crosses as they were of delivering them, and Karim Benzema's flexibility improved their ability to link play from the three deep-lying central midfielders whose positioning provided protection during moments of transition. If their full-backs Danilo and Marcelo advanced, they delayed doing so until Ronaldo and Bale had moved infield; a reliance also existed on the qualities of that front three, who were so often underloaded, and therefore at risk of contributing to sterile periods of possession.

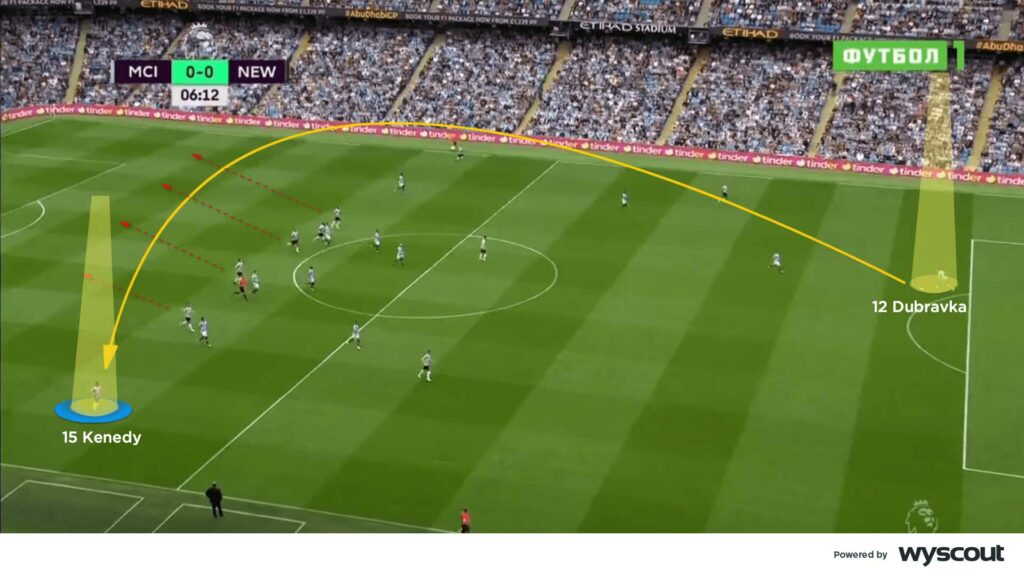

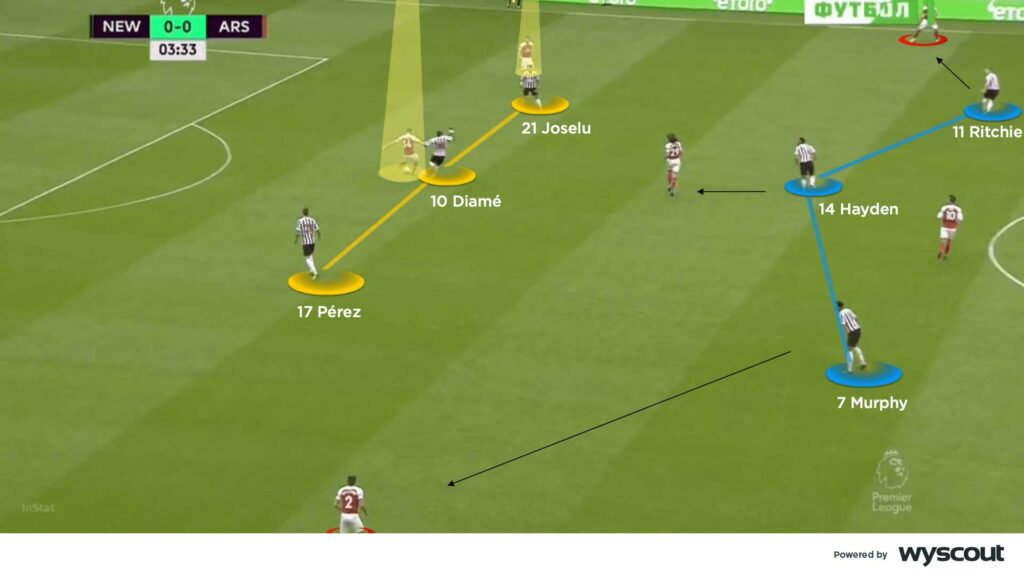

Working with a far lower quality squad in his next position at Newcastle, Benítez organised his team to attack on the counter and via direct balls (below) through or over their opponents' defensive blocks. Possession was often circulated in defence and between Jonjo Shelvey, Isaac Hayden or Sean Longstaff – often withdrawing into deeper positions from central midfield – to create time for those further forwards to assume positions from which they could compete for long-range passes.

In Aleksandar Mitrovic and then Salomón Rondón, strikers capable of winning and then retaining possession after it was played were favoured, and they were complemented by two wide midfielders offering support at the second phase of the relevant attack. Again a 4-2-3-1 was common; later, two inside forwards complemented a central striker in a 3-4-3, in front of wing-backs providing additional width and the back three that had an increased number of targets for their direct play.

Similarly important at Newcastle was the extent to which his attacking players were organised. They worked in defined pairs and were aware of which actions to apply in which areas of the pitch, and also when to do so. When their shape expanded upon regains, their full-backs or wing-backs operated as wider midfielders, their wide forwards moved infield, and their three central defenders and two central midfielders remained withdrawn, braced to defend.

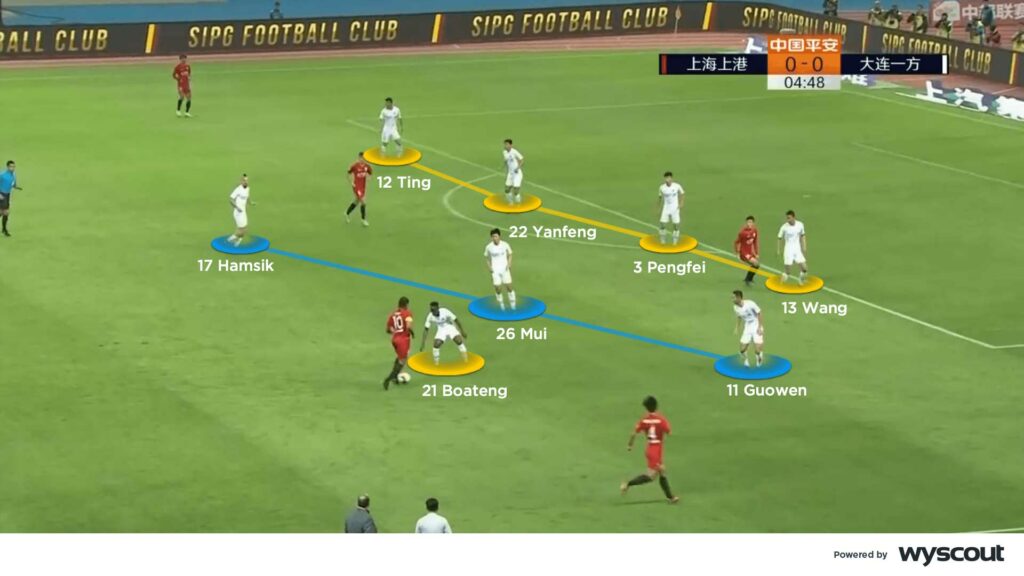

At Benítez's following team, also known as Dalian Pro, Hamsik and Rondòn were again influential, as was the Spaniard's use of both the 4-2-3-1 Napoli impressed with and the 3-4-3 later seen at Newcastle. Dalian applied a controlled, direct approach into Rondòn and Sam Larsson; Hamsik offered supporting runs from midfield, and Wang Jinxian, Lin Liangming, and Sun Bo contributed much of their width.

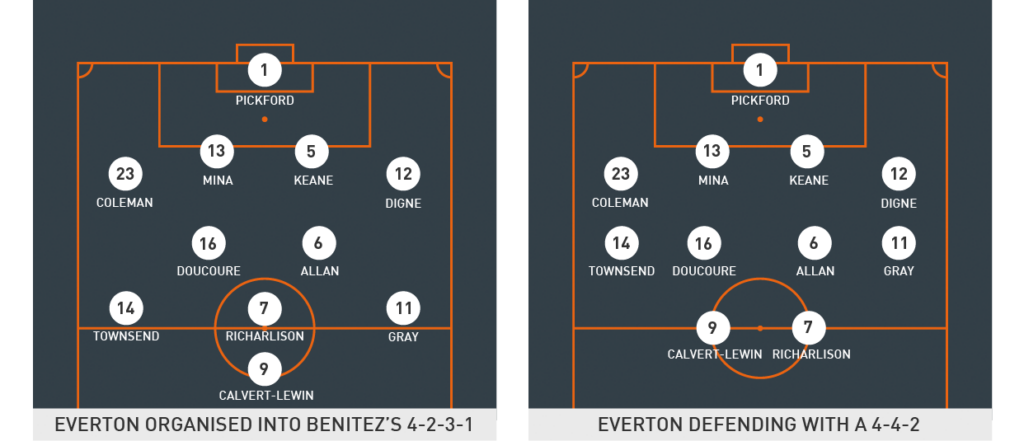

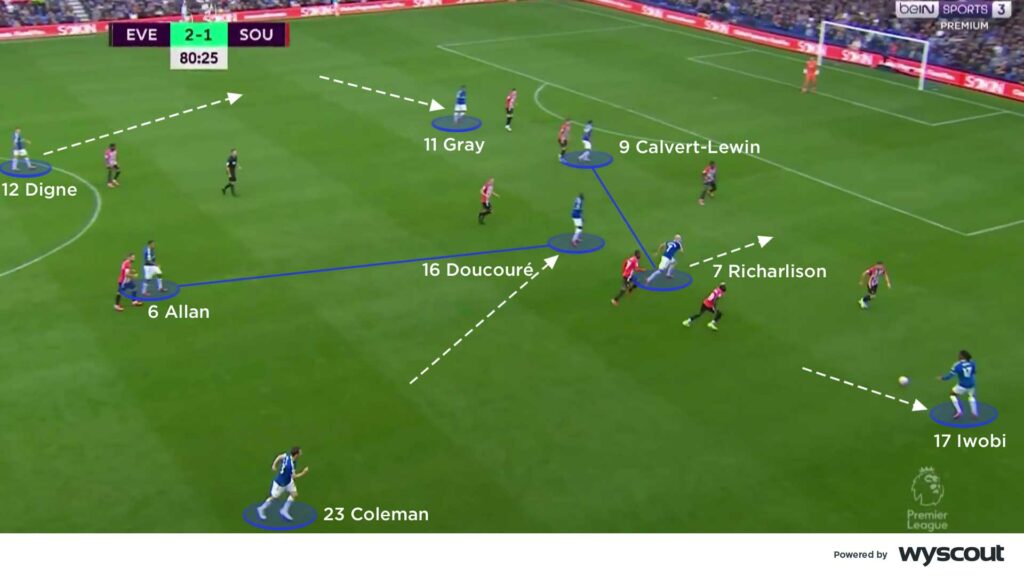

A 4-2-3-1, and less commonly a 4-4-2, were also favoured with Everton. A powerful striker in Dominic Calvert-Lewin or Rondón led their attack, and was supported by a fluid 10 in Richarlison (above), who withdrew to combine, made runs in behind, and, importantly for a manager prioritising building around defensive blocks, attacked crosses and competed against opposing defenders. Injuries to Calvert-Lewin and Richarlison, because of the presence the latter offered in the penalty area, severely undermined them. Benítez also selected Demarai Gray on the left and Andros Townsend or Anthony Gordon on the right so that they cut infield on to their stronger feet – providing increased numbers around their nine and 10 – and targeted second balls aimed towards them.

Those wide forwards' movements created space for their full-backs to overlap into – Lucas Digne provided effective deliveries from the left, complementing how quickly Gray would move infield as well as his desire to dribble, which in turn drew defenders towards him. Townsend's ability to cross with both feet contributed to him remaining wider, on the right, for longer, and therefore their right-back being more reserved. There were times Townsend sought to attack around Everton's opposition, and when he did so Richarlison advanced to between the closest full-back and central defender, leading to Abdoulaye Doucouré also advancing from the base of midfield. Townsend and Gray were both influential during moments of transition, when they often led counters; their preferred movements also led to their nine and 10 drifting to the right to encourage Gray infield when they did.

Defending and pressing

Another consistent feature of Benítez’s teams is their defensive strength (above), which also often involves an adaptable approach. Though Faouzi Ghoulam would advance from left-back, Napoli rarely committed too many numbers forward; those at the base of midfield and at right-back retained their discipline in an attempt to offer protection during moments of transition. Once in a compact block they were difficult to break down via lengthy spells of possession, making transitional, intense counters against them more threatening.

Real were more vulnerable, regardless of the presence of an additional central midfielder, because of the spaces that existed behind their front three at the point of transition – when their full-backs were too often short of cover. His departure from the Bernabéu after only seven months meant he had been presented with little chance to correct that.

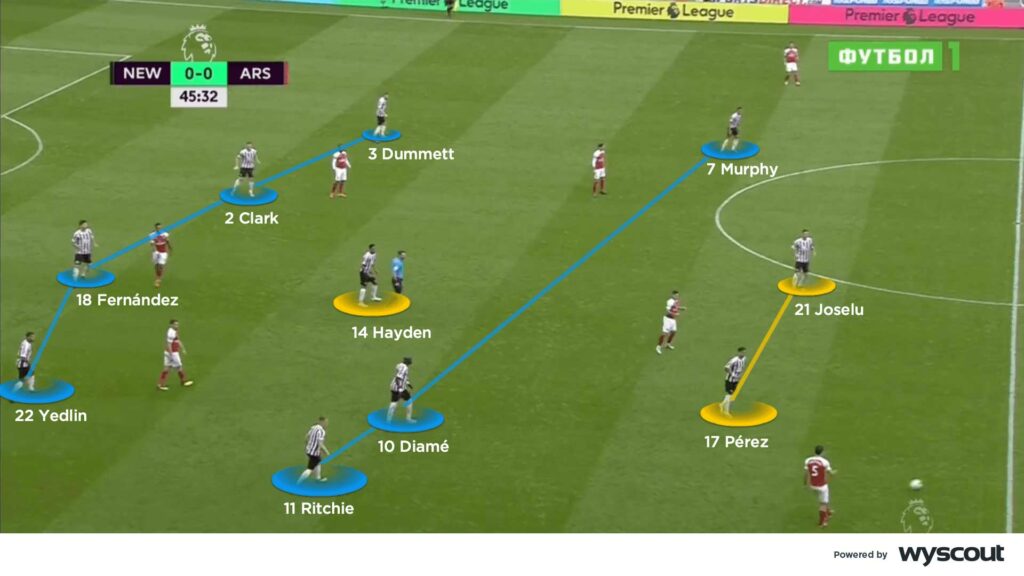

With, by comparison, so little attacking talent at Newcastle, Benítez chose to make his team's focal point its defence. He again convinced his players of the importance of a collective organisation over that otherwise potentially placed on individuals; Newcastle were regularly seen adopting medium-to-low defensive blocks, defending close to their goal, and initiating their desired press (above) from short distances.

Their 4-5-1 often became a 5-4-1 or a 3-4-3, depending on the challenge presented by their opponent, and further variety (below) existed within those systems. In their 5-4-1, one of their three central defenders adopted a more withdrawn position to operate as a sweeper and cover both full-backs or another central defender should he advance to press, ultimately preserving a back four.

Once in a mid-block, and therefore with a reduced emphasis on defending the spaces directly in front of their goal, Newcastle's players were given specific roles determined by the territory in which they were defending, and therefore how suitable it was for them to take potential risks. A decision was made, when preparing for the relevant fixture, regarding whether to prioritise regaining possession via their pressing approach, cutting out passing lines, or intercepting passes. Their approach to making regains was then determined by what offensive options were taken upon those regains.

More consistent was the moment in which the players nearest the ball, the players furthest, and those in between them detected the moment to press. Attention was paid to the potential destination of the ball and whether to target the pass, the receiving player, or to wait for the ball to be received, and spaces were often closed to enhance a teammate’s subsequent individual press. Regardless of those variables, a sense of balance, and an awareness of the wider team’s needs, was always retained.

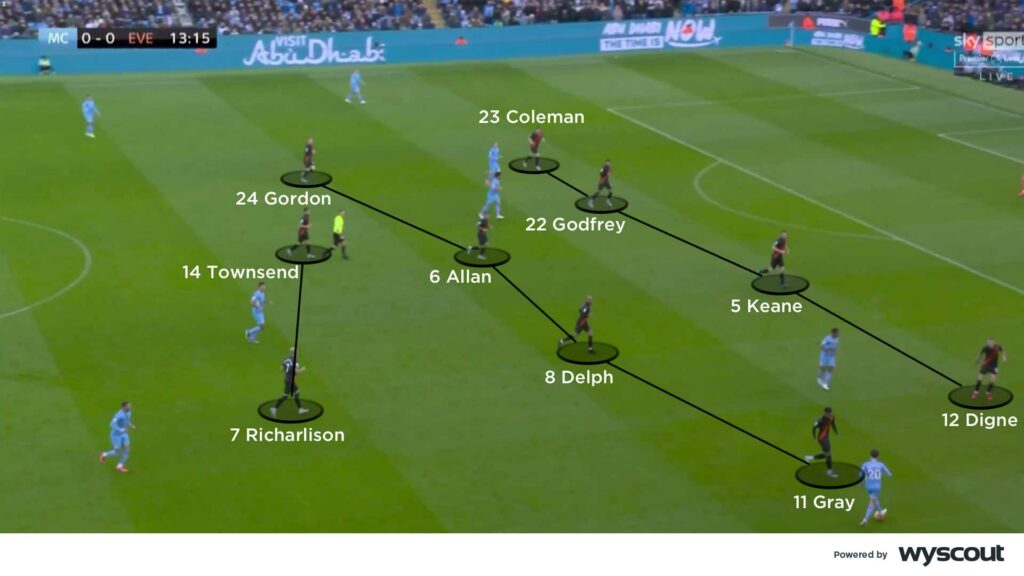

Everton regularly used mid and low blocks, and their 4-2-3-1 often became a 4-4-2 via their 10 advancing (above) to screen the defensive midfielder opposite him; they rarely pressed into the attacking half. As a consequence opponents were often forced wide, where Everton's midfield line then moved in an attempt to contain the ball. Their wide midfielders defended from narrow positions, and often did so after one of their front two had already forced possession away from central territory; if it progressed beyond them their full-backs moved wide to press the ball.

When that led to space in their defensive line, one of Doucouré or Allan withdrew to fill it and protect against attempts to attack back infield and through the inside channels, and their midfield line, in turn, was supported by their 10 retreating. It was when play was built on the same side of the pitch as their striker that that same compactness and cover didn't exist. Between them, Everton's two defensive midfielders also tracked runs made early and through the inside channels, and were complemented by their 10 resisting moving to form a front two. That that was the case meant cover was provided against forward passes and runs, but at the expense of central territory – which encouraged opponents to progress possession via a defensive midfielder – and also Everton's potential on the counter.

Their full-backs pressing wide, and their central defenders therefore moving to provide cover, also undermined their compactness in central defence, making them vulnerable against secondary runners and penetrative combinations from a third man. If Benítez's team also conceded possession in the midfield third, they were similarly vulnerable to opponents advancing beyond their double pivot, and partly because of the ineffectiveness of Everton's players to delay opposing counter attacks and secure time for their teammates to recover back into defence.