What is the 3-2-4-1 formation?

The 3-2-4-1 formation features three players in the back line, operating underneath two deeper central midfielders. This pair forms the base of the midfield unit, which is usually a box shape. Further ahead in the central areas are two attacking midfielders, who try to position themselves between lines, completing the midfield box. One player operates in each wide area, working either side of a single centre-forward.

The 3-2-4-1 formation can operate as a fixed structure, with three centre-backs forming the back line, and two wing-backs working around the midfield four and central striker (below). However, a growing trend in the modern game involves teams attacking with a 3-2-4-1 but defending with a back four. This requires at least one of the back line to move into a new position when attacking, with the remainder of the back line swinging around to form a three.

How did the 3-2-4-1 originate?

The 3-2-4-1 formation is essentially the modern version of the W-M formation, which Herbert Chapman’s Arsenal popularised with their success in the 1930s. The W-M added another defender to counteract increasing attacking numbers at that time – a result of a change in the offside law. Later, teams playing back-five systems used a 3-2-4-1 when attacking. That meant wing-backs advancing forward and working around a central midfield box when attacking, but reverting to a 5-4-1 or 5-2-3 shape when defending (below).

In the 2020s the 3-2-4-1 emerged again, with coaches who want their team to defend with a back four but attack using a back three. This can mean one defender advances from the back line, such as a full-back inverting into midfield. Or it can be two players – usually full-backs - advancing from the back line at the same time. In that case, a single player – usually the deepest central midfielder – moves the opposite way, dropping in between or alongside the remaining centre-backs.

The rest of the midfield and forward unit then readjust to form a box of four in midfield, operating between a front three and the back line. Both Pep Guardiola and Marcelo Bielsa are modern examples of coaches who have used these methods to convert a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1 into a 3-2-4-1 attacking shape.

What are the in-possession responsibilities in a 3-2-4-1?

The 3-2-4-1 places significant attacking numbers directly up against the opposing back line. The single centre-forward can operate between two centre-backs, which allows two attacking midfielders to make forward runs and combine in the inside channels, providing crosses and shots.

The wingers stretch the opposing back line across the pitch. They attack from the wide areas, providing crosses, attacking combinations and sometimes shots after cutting back inside.

With the front three often pinning the opposing back line, the two attacking midfielders also have licence to drop, to rotate and connect with deeper players (below). This can help overload the opposition’s central-midfield unit, allowing for lots of short passes and attacking combinations to help progress up the pitch.

The double pivot supports underneath the attack. Along with the two attacking midfielders, the pivots can assist with dominating the ball in the central spaces. They are the link between the back three and the rest of the attacking unit, collecting passes under pressure to then progress play with a range of passing.

The back three support the goalkeeper with deeper build-up when a team’s style is short passes through the thirds. The widest of the three often have space to drive into, so they will frequently carry the ball forward. The middle centre-back often drops deeper to help pass the ball across the pitch, or away from pressure. If a team builds more directly, the back three have the opportunity to deliver longer passes or switches of play, often direct to the wingers or centre-forward.

What are the out-of-possession responsibilities in a 3-2-4-1?

As the 3-2-4-1 is more of an attacking shape, it converts into various defensive structures, with either a high-pressing strategy or more cautious mid and low blocks. The centre-forward can lead the press by locking play one way, as the rest of the team shuffles across to force the ball down one side of the pitch (below). Alternatively, the centre-forward can play a more reserved screening role, to block central passing lanes and cover or intercept passes through the middle.

The wide players support a high press by jumping alongside the centre-forward. The winger opposite to the ball will often narrow, giving further compactness in the centre to limit attempted switches of play.

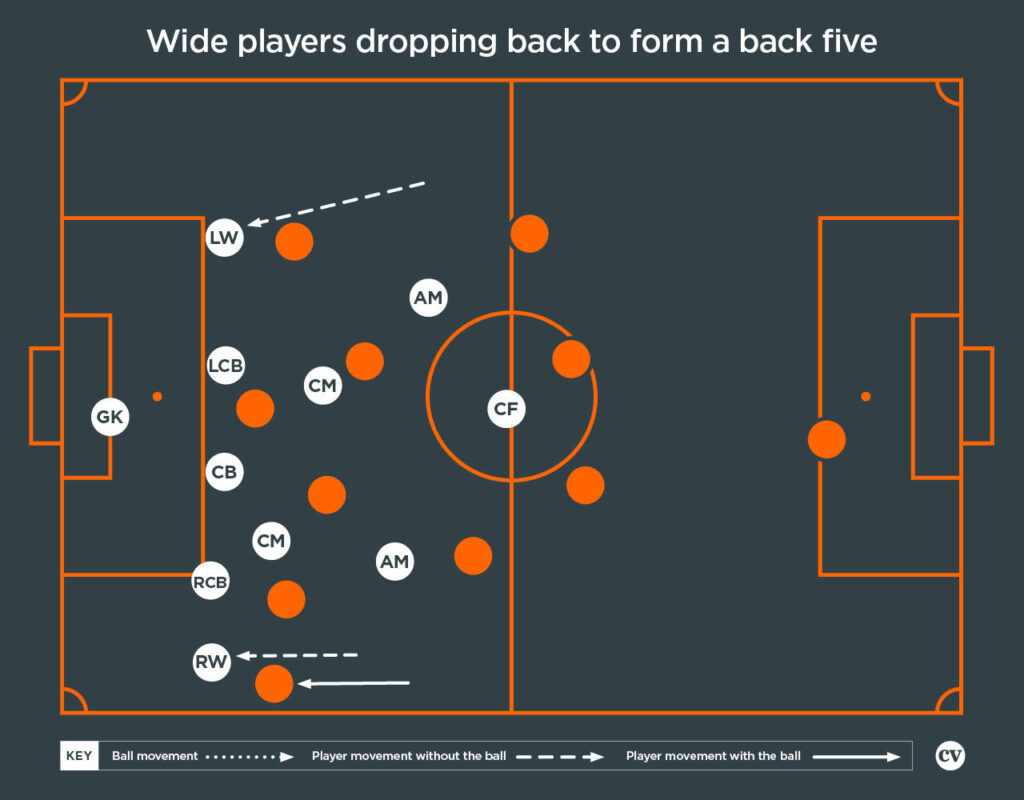

The wide players may also recover back into a deeper defensive position, especially if an opposition full-back has advanced in attack. This can help form a four-player back line. Should both wide players recover back, they help to form a back five, often in a deeper block (below). The wide players then focus on blocking crosses and stopping passes into the penalty area.

A winger who inverted when attacking can move back out wide to defend, leaving two or three players in the midfield unit to defend the central spaces. This is often player-oriented defending, as well as covering and screening.

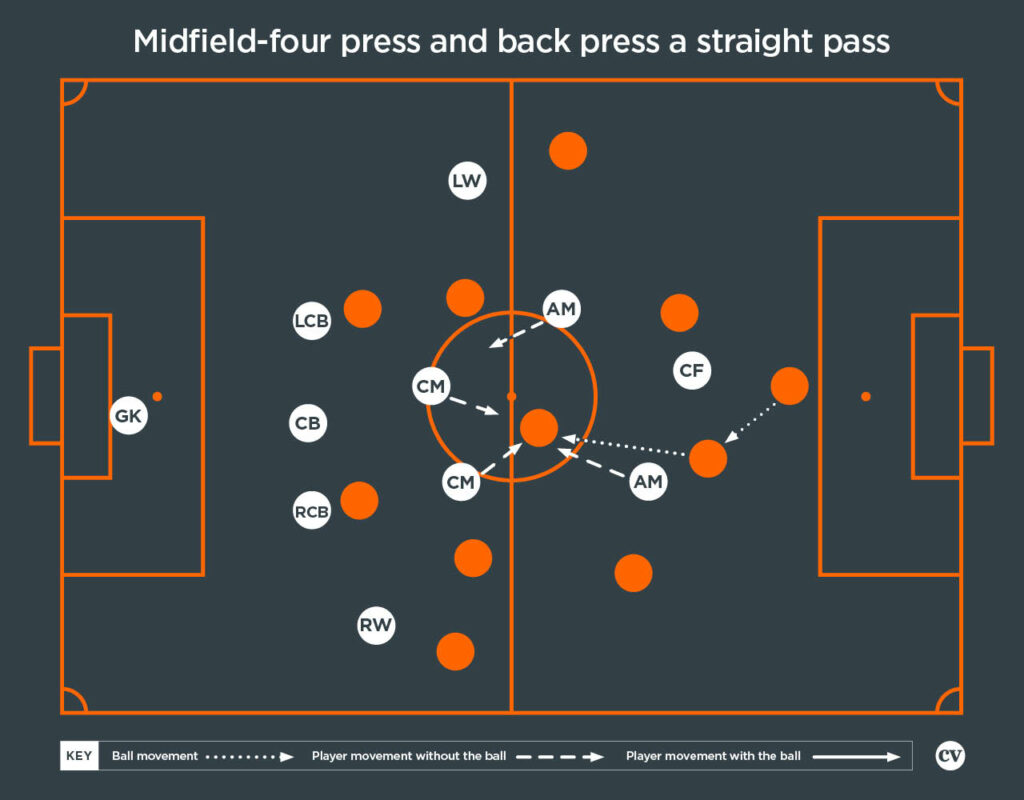

Should the midfield unit of four remain, then the attacking midfielders can release to support high pressing in place of the wide players. The two deeper midfielders support the press as the second line, often moving wider to help lock the play one way. Alternatively, they aggressively jump on to straight passes into midfield, with the attacking midfielders back-pressing and sandwiching the opposing midfielder trying to receive (below).

As with all defences, the back three should remain as compact as possible for as long as possible, encouraging or forcing play away from goal. The three centre-backs often have cover and protection ahead, thanks to the double pivot. The wide areas, however, are often vacant – especially during transition – meaning that the widest players in the back line may have to defend towards the touchline for longer.

When supporting a high press, the back three may also need to be player-oriented with their marking against a front three. That places increased emphasis on their individual duelling and 1v1 defending. When teammates recover back into the defensive unit, to form either a back four or five, the focus is on protecting the centre, forcing play away from goal and limiting goalscoring opportunities.

Examples of teams using a 3-2-4-1

Unai Emery’s Aston Villa

Under Unai Emery, Villa have typically defended in a 4-4-2 or 4-4-1-1, but switched to a back three in possession. He has encouraged one of his full-backs – usually Lucas Digne – to advance and create the width on the left. The likes of Jacob Ramsey, John McGinn, Nicolò Zaniolo and Morgan Rogers have moved inside from a wide-left starting position, as the number 10 readjusts into the right inside channel. The double pivot remains fixed, completing the box shape ahead of the back three, which moves across to the left (below).

Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal

Mikel Arteta has often utilised a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1, but converted it to a 3-2-4-1 by moving a full-back into a pivot role, as opposed to them pushing high and wide. Oleksandr Zinchenko has often performed that role (below) – although Myles Lewis-Skelly stepped into his boots in the 2024/25 season – with Arsenal’s remaining back line swinging around. One of the midfielders then bumps forward to become a second number 10 alongside Martin Ødegaard, who readjusts accordingly.

Enzo Maresca’s Chelsea

Enzo Maresca has a history of encouraging a full-back to advance from the back line, whether to a high and wide position, or to form a double pivot. He has also placed the likes of Malo Gusto and Marc Cucurella into one of the attacking midfield roles, working alongside Cole Palmer as the latter readjusts into the right inside channel (below). In this case, the double pivot remains fixed as the back line swings around. The front three remains intact, with the wingers holding the width (below).

Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City

Pep Guardiola has used many varieties and rotations to form a 3-2-4-1. Unlike most coaches, he has often converted to a back three by pushing a centre-back into the double pivot, alongside Rodri. Guardiola has used this option when his back line has been made up of players with more of a centre-back profile, or he has had a full-back who is also comfortable at centre-back. The likes of Kyle Walker, Nathan Aké and Manuel Akanji have all defended in full-back roles, before narrowing to form a back three as a centre-back moves into midfield. John Stones (below), Fernandinho and Akanji have all advanced to play alongside Rodri during the build phase. City have then bumped one of their midfielders higher as a second number 10, underneath the single centre-forward.

What are the benefits of playing with a 3-2-4-1?

The 3-2-4-1 places eight out of the 10 outfielders through the middle of the pitch. As such, it is one of the few structures that has four players permanently in central midfield. This helps to overload and control the midfield, bossing possession. From here, build-up from the back and regular attacks can occur via this central unit.

When a team in a 3-2-4-1 loses possession, counter-pressing can immediately stop counter-attacks and work to regain possession quickly, courtesy of the four players in central midfield. This supports quick counters when the opposition has just begun to open up. The presence of four central players in midfield also helps with winning first and second balls, and dealing with direct play.

A team can form a 3-2-4-1 from different formations, with players moving into new attacking roles. It also has enough flexibility for players to easily work themselves into different positions to attack. That means coaches can use it to get the best out of the specific players they have available, rather than the formation being rigid, with attacking options that don’t suit the players.

This shape also lends itself to quickly forming aggressive high pressing, due to the numbers in attack. The front three, supported by the two attacking midfielders, can put almost instant pressure on the opposition back line and deeper midfielders. It is also a shape that can quickly form a compact block, especially with three centre-backs and a double pivot protecting the middle from counter-attacks. With wide players recovering quickly, a team in a 3-2-4-1 can form a significantly compact block, often before the opposition have been able to create an attack.

What are the disadvantages of playing with a 3-2-4-1?

Coaches have often used a 4-2-4 to nullify a team attacking in a 3-2-4-1. The full-backs in a 4-2-4 defend the wingers in the 3-2-4-1, with both attacking midfielders also tightly marked, by the opposing double pivot. The 4-2-4’s centre-backs overload the centre-forward, while their two wide players are often able to cut off wide access between the 3-2-4-1’s centre-back and wingers. The two forwards in the 4-2-4 can then protect and cover access into the double pivot of the 3-2-4-1, helping lock the ball down one side.

The wider of the three centre-backs in the 3-2-4-1 have to be extremely versatile and comfortable enough on the ball to outplay opponents. Furthermore, the distance between the wide centre-backs and their winger can often be stretched. A wide centre-back’s option will often be long, straight passes into the winger, who can be locked along the touchline and forced back. This can result in a fairly simple pressing trap where the 3-2-4-1 locks itself on one side. Additionally, in the absence of full-backs or wing-backs, if the wide centre-backs aren’t comfortable or athletic enough to defend in the wide areas, the back line can become stretched, isolated and exploited.

The wide players can be isolated in a 3-2-4-1. This places a big emphasis on their 1v1 play, especially ball-carrying, dribbling and duelling. The single centre-forward, meanwhile, is usually up against two centre-backs. Unless they receive regular service, they can also become isolated. And they can face a tough physical battle, as they must receive, hold, link and attack against two opponents.