What is a 4-3-3?

The 4-3-3 is a formation that uses four defenders – made up of two centre-backs and two full-backs – behind a midfield line of three. The most common set-up in midfield is one deeper player – the single pivot – and two slightly more advanced to either side. The front line is then composed of two wide attackers who play on either side of a single centre-forward.

Where does the 4-3-3 originate from?

In response to the 1950 World Cup final defeat at home to Uruguay, Brazil started to use a back line of four in a 4-2-4 formation. They went on to use this formation at the 1958 World Cup, which they won. By 1962, Brazil had adapted once more to create a 4-3-3 structure in which Mário Zagallo dropped from the front line into midfield.

At the next World Cup, in England in 1966, the hosts and eventual winners used a more permanent defensive midfielder – Nobby Stiles – in a 4-1-2-3 formation.

Although the 4-3-3 was then used across Italy, Argentina and Uruguay for years to come, Rinus Michels’ Netherlands and Ajax sides of the 1970s were two of the most famous for inspiring the use of a 4-3-3 shape. It was these teams’ tactics that led to the concept of Total Football and encouraged the likes of Johan Cruyff to use a 4-3-3 when he became a coach, too.

What are the players' in-possession responsibilities in a 4-3-3?

The main responsibility for the wingers is isolating full-backs and attacking in one-on-one situations – either working around the outside of their opponents to cross, or cutting inside to combine. The latter approach is common for wrong-footed wingers or inside forwards, who aim to come off the flank and shoot at goal. Wingers holding a wide position can help create space infield for an attacking midfielder to run into. A winger moving infield, meanwhile, creates space on the outside for a full-back to overlap into.

The lone centre-forward moves across the pitch as the attack builds, pinning the opposition’s ball-side centre-back. The forward can drop short to link and help create overloads in central midfield, or provide direct runs beyond the opposition. These runs are often to try and get on the end of through balls, and in the process push the opposition’s defence back into deeper territory. This will, in turn, create space centrally for midfielders or wide forwards to move into.

The midfield three provide passing options for both build-up and attacking play. The two more attack-minded midfielders are often positioned in the inside channels and provide forward runs between the winger and centre-forward to get into crossing positions. If deeper, they connect the full-back and centre-back on their side to the winger and centre-forward. The defensive midfielder is the primary link between the back line and midfield, though, and the main player through which switches of play are made to access the other side of the pitch.

The back line – especially the centre-backs – focus on accessing the central midfield unit during build-up, especially if they have an overload in that area. The centre-backs will also often reposition themselves to allow the deepest midfielder to drop into the back line during build-up. The full-backs then push forward, providing the team’s width as the wrong-footed wingers move inside. Then, the attacking midfielders may remain deeper, acting as cover should the move break down.

What are the players' out-of-possession responsibilities in a 4-3-3?

Having three players in attack means a 4-3-3 is a good shape to use to press high up the pitch. The wingers can start narrow to block the central areas before pressing outwards to force the ball wide, with the centre-forward aiming to block off any switch of play. It is also possible for the wingers to start wider and press inwards, should the aim be to force play into a midfield trap. Another option is the wingers positioning themselves in line with the two outside central midfielders to form a 4-1-4-1 block.

The three central midfielders cover and protect central areas, and can quickly adapt to become two defensive midfielders and one advanced midfielder if necessary. This can occur either when a block is formed or when pressing. When set in the more traditional 4-3-3 shape – with one defensive midfielder flanked by two others – the advanced midfielders can individually press the wide areas behind the wingers, or jump to support the centre-forward.

The back four will remain compact for as long as possible when defending in a set block, protected by the midfield three. Opponents can target spaces out wide, between the full-back and winger; here, the back line can move across the pitch aggressively. The full-backs may jump forward to support a higher press, especially if the winger on the same side is committed forwards. The back line will again slide across the pitch to support the full-back.

Which are the best examples of teams using a 4-3-3?

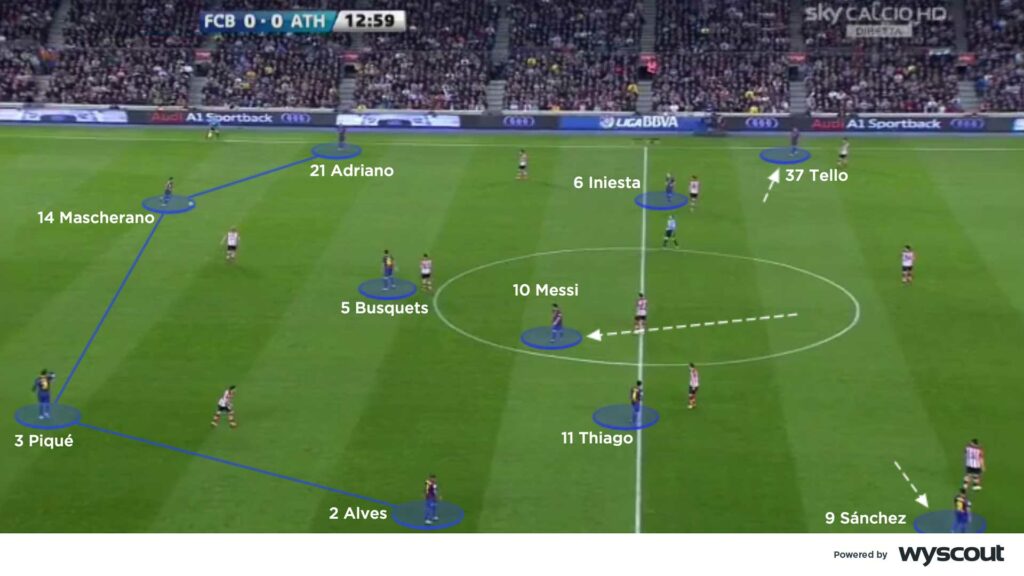

Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona

Guardiola has often used a 4-3-3 as his preferred starting shape. With Barcelona, the width was created by wingers such as Lionel Messi, Pedro, Cristian Tello or Alexis Sánchez, or converted wide forwards in Thierry Henry and David Villa (above, top). Playing with high, wide players worked to pin back the opposition’s back line. This created space in the inside channels for Xavi, Andrés Iniesta or Thiago to dominate possession, and feed play into the forwards. A dropping centre-forward – or false nine – in Samuel Eto’o, Messi or Cesc Fàbregas further overloaded areas in central midfield.

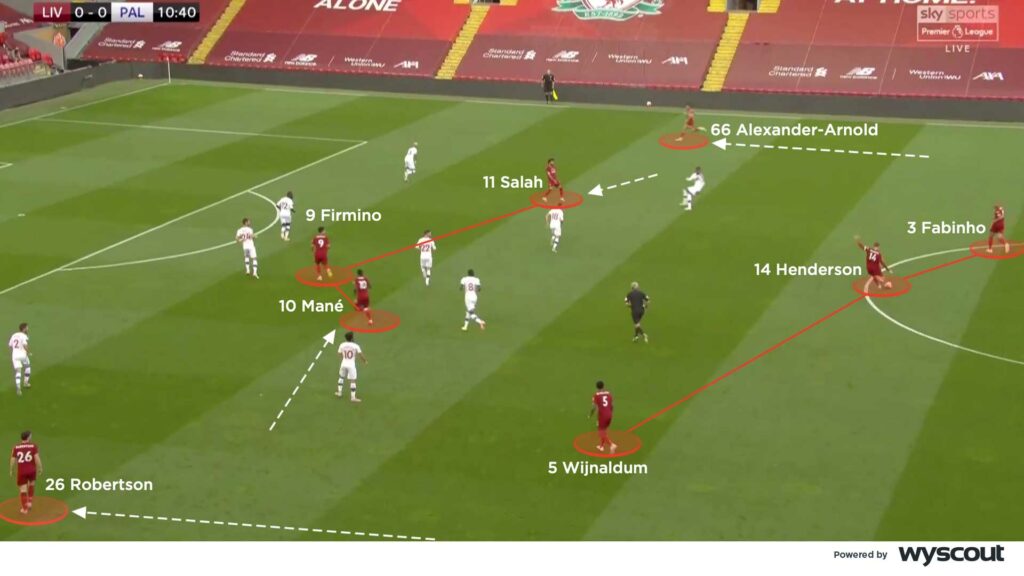

Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool

In Klopp’s 4-3-3, wrong-footed wingers Mo Salah and Sadio Mané moved inside, allowing full-backs Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andy Robertson to overlap and provide crosses, cut-backs and the majority of the team’s width (above). Jordan Henderson and Georginio Wijnaldum, playing just ahead of single pivot Fabinho, provided support underneath the ball. Centre-forward Roberto Firmino offers forward runs to threaten in behind and combine high up the pitch, but just as commonly drops in to midfield to create overloads.

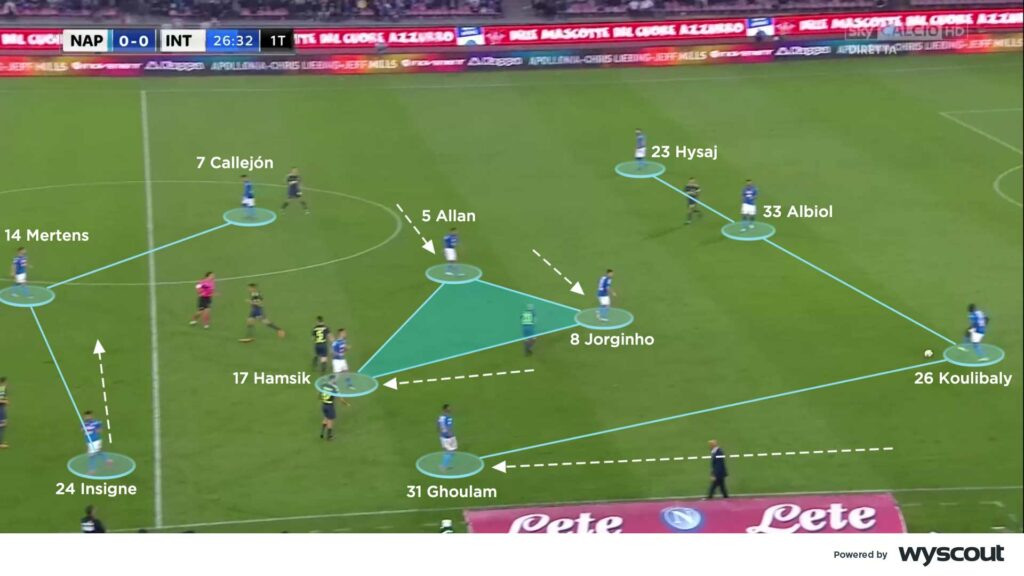

Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli

Sarri’s 4-3-3 used a blend of wingers and overlapping full-backs to provide the team’s width, often in an asymmetrical style and with different combinations on each flank. On the left, right-footed winger Lorenzo Insigne would cut inside, and left-back Faouzi Ghoulam overlapped. Marek Hamsík made forward runs through the left inside channel as part of the rotations on that side. On the right, right-footed winger José Callejón held the width, with right-back Elseid Hysaj more often keeping his position in the back line – especially when Ghoulam pushed forward (below).

What are the benefits of playing with a 4-3-3?

The 4-3-3 creates natural triangles, often giving the player in possession several passing options at any given time. This makes implementing a possession-based style of play slightly easier than some other formations.

The three-player midfield unit can create overloads in central areas, which will further help attempts to dominate possession. A dropping centre-forward or inverted full-back can add another body in midfield. This can help retain a central overload, should the opposition also set up with three central midfielders.

The formation also makes it easy for lots of players to move forward and attack. Many teams playing in a 4-3-3 will end up with a front line of five, with the centre-forward and wingers accompanied by the full-backs or attacking midfielders.

The 4-3-3 is also a good formation from which to press. A three-man forward line provides good numbers to apply pressure on the opposition defence. The midfield three then provides cover and protection in central areas. This is useful both when pressing high or converting into a more reserved block.

What are the disadvantages to playing with a 4-3-3?

The space left in the wide areas between the full-back and winger in a 4-3-3 can be exposed and targeted by the opposition. This is usually via quick counter-attacks and swift, direct switches of play.

With this formation encouraging players to push forward and join the attack, teams can leave themselves short of numbers when it comes to slowing or stopping opposing counter-attacks. Opponents can then progress further following a transition, meaning bigger and more frequent recovery runs back into shape. This increases the physical demands on the players.

A lone centre-forward can be isolated in attack if they lack support from the wide attackers or advanced midfielders, and as such can find themselves numerically underloaded against opposition centre-backs. This can also mean too little attacking presence in the penalty area if teammates fail to make supporting runs.

Want to know more about football tactics and learn how to coach from the very best? Take a look at the Coaches' Voice Academy here.