adama traore

Wolves, 2018–

Profile

Having been allowed to leave Barcelona at the age of 19 after 11 years, Adama Traoré has taken an unusual route to the top. Via spells of increasing success at Aston Villa, Middlesbrough and Wolves, Traoré – since an international with Spain – has become one the world's most dangerous wide forwards. The manager under whom he has made the greatest progress, Nuno Espírito Santo, remains among his many admirers.

“The way he took the team up, the way he created, the way he unbalanced the opponents, he can do all this and other things,” Nuno said after one particularly impressive showing while he still manager of Wolves. “But he has to improve a lot. This time he was stable in defence, covering his centre-back, winning balls in the air. We’re building a player.”

Tactical analysis

Traoré is at his best playing on the right side of a front three, where he can use his pace and dribbling ability to pose a direct threat on the opposition's goal. He is most effective with space to attack behind an opponent, so he regularly positions himself on the outside of the defending full-back and close to the touchline, leaving enough space to run at his opponent and attack in behind.

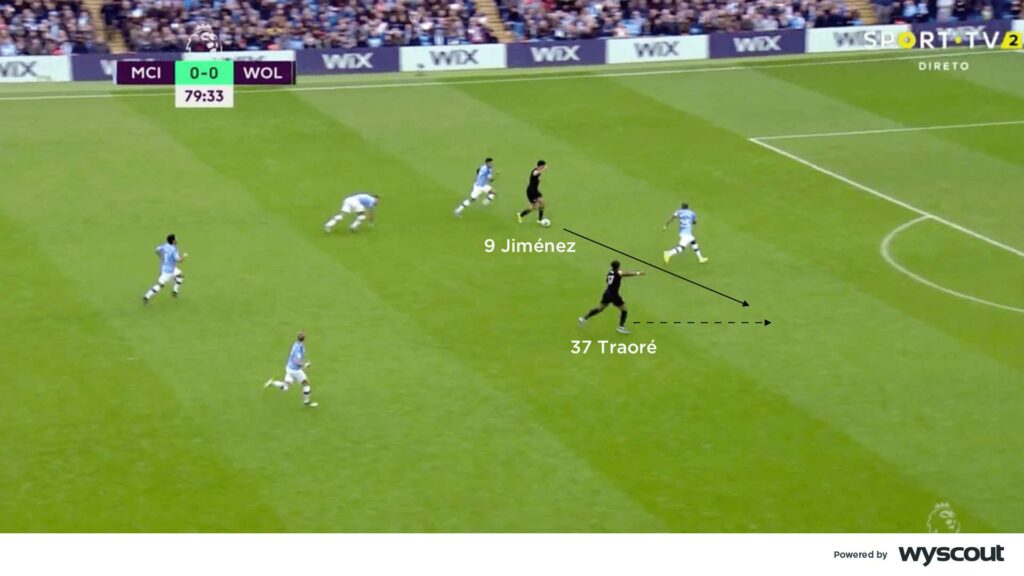

He will often look to run on to a pass in behind from a teammate (below), but if the opposition's defence withdraws into a deeper position, Traoré will instead offer an option to feet after pulling wide. He then approaches his direct opponent and slows right down – sometimes to a complete stop – before accelerating away at pace. Few defenders are able to contend with Traoré when he isolates them in that way.

When he is on the ball in a wide position, his attempts to beat an opponent are often predictable (below) – they most commonly involve him using the outside of his right foot to move the ball beyond his opponent before running on to it and attempting to cross – but that doesn't mean defenders are able to stop him easily. His preference after beating a defender usually involves chipping a cross towards the back post when he tries to set up a chance immediately after manoeuvring past the outside of him.

However, as defenders became more accustomed to his movements, he started to vary his approach by occasionally taking a touch diagonally back inside his opponent to provide a better angle from which to play the ball into the centre and intentionally pick out a specific teammate rather than delivering a hopeful cross into the area. He is also more comfortable coming off the wing than he was, and will often be found dribbling straight through the centre of the pitch to lead a counter-attack, when his teammates will make runs out to the wings to create space for him through the middle. That has even led to him occasionally playing as a second striker, and he has also improved his decision-making in central areas, leading to a number of impressive goals scored from distance.

When he receives to feet with his back to goal and with pressure behind him, he uses his body well to protect the ball, and then often takes a touch with the inside of his right foot while using his arm to maintain protection of the ball to roll past his opponent and on to his favoured right side. He has improved significantly in those situations, and is far more skilled at dribbling out of tight situations than he once was.

Role at Wolves

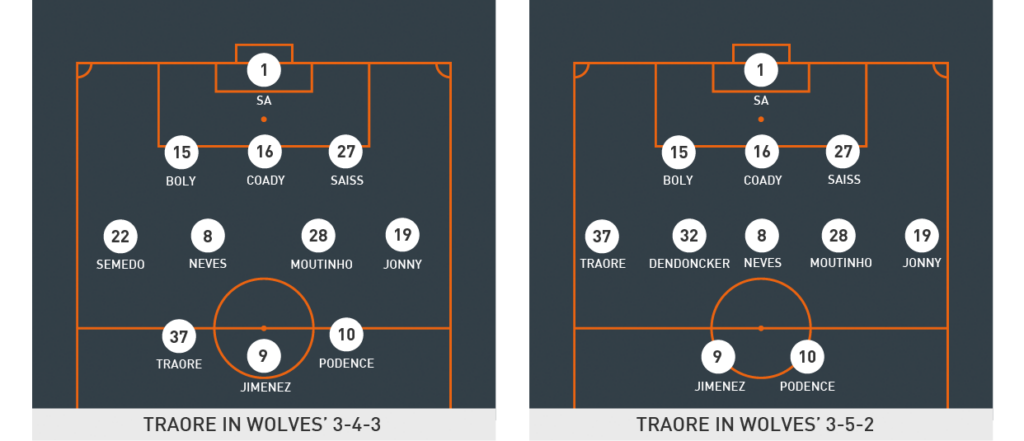

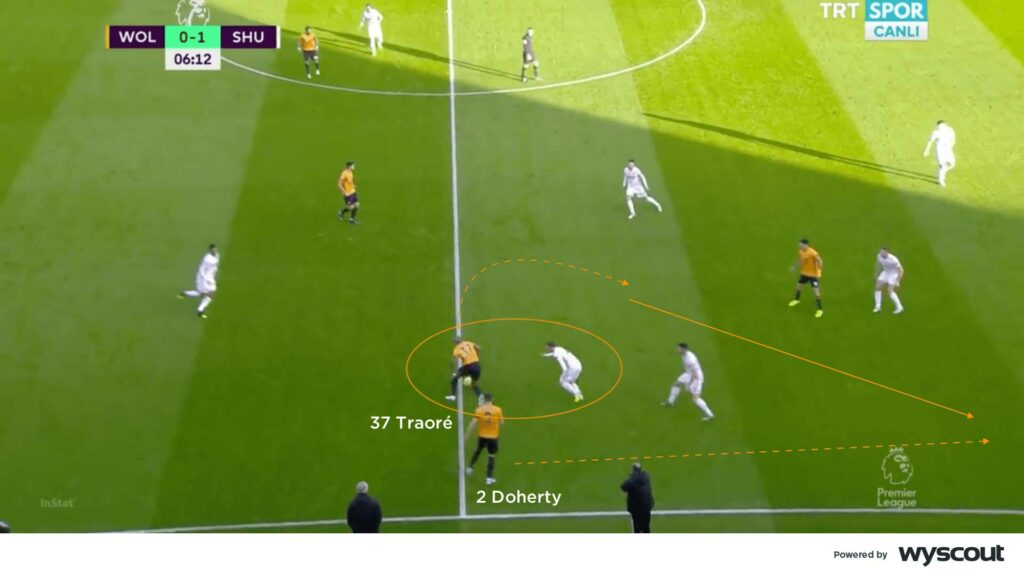

After intermittent and ineffective experiments with Traoré on the left side of their attack, he was most regularly deployed as the right-sided attacker in the 3-4-3 formation Nuno preferred. From there he once formed one of the Premier League’s most dangerous partnerships with their right wing-back Matt Doherty, with whom he had a brilliant understanding. They understood one another’s games and dovetailed with underlapping and overlapping runs to create space for the other, but Doherty’s departure to Tottenham in the summer of 2020 left Traoré one helper down.

Traoré even filled in at wing-back, which may have been a nod to Nuno wanting to have one of the best dribblers in the Premier League more involved in play. Playing him in a deeper position, however, reduces the threat he poses during transitions, because he is further from goal and opponents – who regularly take to fouling him to halt his progress – have more chance to close him down.

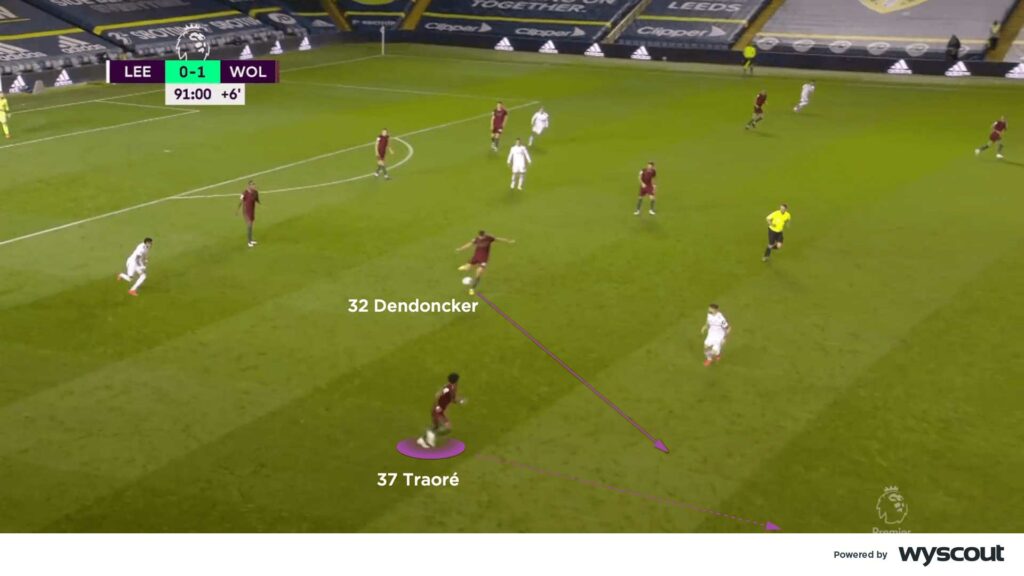

Offensive transitions are the situations in which Traoré is most threatening. When Wolves do not have the ball he adopts a position that invites his teammates with better passing ability – such as João Moutinho, Rúben Neves and Leander Dendoncker – to quickly release him into space (above). Once he gets going there is often little stopping him.

His teammates benefit from his direct running, dribbling ability and the frequency with which he wins free-kicks in dangerous areas, but they also recognise the need to make runs that create space for Traoré to attack because he can carry them up the pitch quickly (above). His final ball still needs to improve, but his ability to gain territory through sudden bursts forward (below) is so useful that his flaws can be rendered almost meaningless.

Without the ball, Wolves usually drop into a 5-2-3 mid-block, but Traoré is often too passive, which will likely contribute to his long-term future being further forwards than at wing-back. He likes to play his natural game and to work on instinct, which is hugely effective, but previous managers have found that frustrating. At Middlesbrough, Aitor Karanka routinely switched Traoré's position at half-time so that he remained near to the dugouts and could hear Karanka’s constant instructions.

Since then he has improved significantly in that regard, and is alert to the possibility of a turnover and a swift transition to attack. So vast is the threat he offers if the ball comes his way that Nuno sometimes does not ask Traoré to track back too far; he instead stays high up the pitch to pin back the opposing left-back.

Such has been his improvement at Wolves that there is no question Traoré could play at a higher level. He could even eventually follow Diogo Jota to a club in the Champions League.