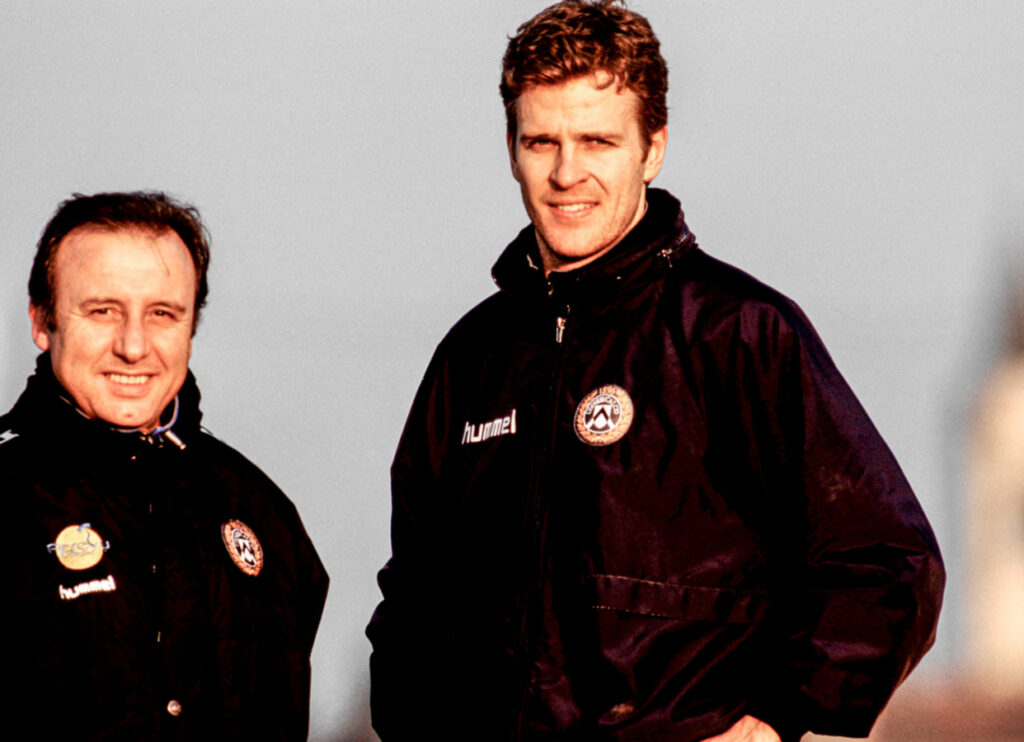

alberto zaccheroni

Udinese, 1995-1998; AC Milan, 1998-2001

I’m still the same person who grew up in Cesenatico, Italy, and started his managerial career with the Under-10 team.

My first experience was with the second team from my village, called Ad Novas. Back then I was very young and still an amateur player, but my career was cut short as I suffered from a lung disease that meant I struggled to sustain the same physical preparation as my teammates.

One afternoon, I went for a run on a pitch where two youth teams were training. One of the teams had been left on their own because their coaches had fallen out. They were waiting to start their football practice, and I was asked to look after them. I enjoyed it, and the following day this team was still without a coach, so I did it again. Shortly afterwards, I found myself managing this youth team. My ‘obsession’ as a football manager had begun.

The village’s most important team, Cesenatico, noticed how well I had managed this group of young players. They asked me to become the manager of their Under-16 team.

The Cesenatico senior team was bottom of the table in Serie C2 – Italy’s fourth division. They sacked the manager but didn’t have the money to hire a new one. So they asked me to take charge of the team.

Back then, I did not even have my coaching badges, so I needed special permission from the FIGC – the Italian Football Federation. We managed to avoid relegation; I won six games and drew four of the last 14, but the following season I went back to managing the Under-16 team.

But then, again, with only three months left to complete the season, the club sacked the manager and asked me to step in. Again, we managed to avoid relegation, but it was disappointing. I understood the club was not interested in developing young players, and were using me only to fill a gap.

"a system is like a dress – it must highlight the players' virtues and hide their flaws"

At the end of the season, I was hoping Ascoli would hire me to manage their ‘Primavera’ – Under-19 team – but it did not happen. However, I started to receive many offers from local teams, and in 1985 I accepted the offer to manage Riccione in Serie D.

In my first season in charge at Riccione, we qualified for the playoffs, but we lost in the final. In my second, we won the league. I won that division twice – the first time with Riccione in 1987 and the second time with Baracca Lugo in 1988. With Baracca Lugo, we also won Serie C2 the following season. They were fun times.

I was lucky to manage in all of Italy’s professional football divisions; I got to see players of different levels, and I had time to grow as a manager. I made mistakes, and I learnt from them.

Above all, I learnt that it is more important to play a system that can get the best out of the players rather than trying to impose my vision of football at all costs. A system is like a dress: it must highlight the players’ virtues and hide their flaws.

Being flexible is important. I have always focused on improving every single player by putting them at the core of my project and by showing them, during training, how they could improve.

For example, back in the late 1980s, not everyone in Italy was fond of zonal marking. I liked it because I thought it suited some of my players better at that time, although I knew my football directors and chairmen were not convinced at all.

"johann cruyff gave me a lift in his car – my legs were shaking with emotion"

Everyone remembers me for the good results my teams achieved. In 1991, I managed to get Venezia promoted from Serie C to Serie B after 24 years away; in 1994/95, with Cosenza, we managed to avoid relegation despite having nine points deducted. That year in Calabria was particularly hard – we didn’t even have a proper training pitch. We used the area between the running track and one of the goals.

Udinese gave me more visibility. Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Udinese had been a club used to buying players only at the end of their careers. As a result, they struggled to stay in Serie A for more than a season at a time – they were a yo-yo club.

I shook things up. I gave chances to young players, changed some players’ positions and benched some of the veterans. For example, in midfield I preferred Giuliano Giannichedda, who was 21 at the time, to Stefano Desideri, who had already played for Roma and Inter Milan.

The owners, the Pozzo family, were not happy initially. I knew I was forcing their hands but, game by game, I managed to convince them. After my first season in charge – the 1995/96 season, when we finished 11th as a newly promoted team – the whole philosophy of Udinese changed. The club started scouting and recruiting young players from all over the world.

At all the clubs I managed, I only once asked for a player to be bought – that was in 2004, when we signed Dejan Stankovic (above), who I knew well from my time managing Lazio, for Inter. Instead, I always worked to improve the players already at the club – and this is what happened in Udine.

Jonathan Bachini, Raffaele Ametrano, Marco Zanchi, Márcio Amoroso, Mohammed Gargo, Stephen Appiah… these are just some of the players I improved at Udinese. Amoroso was a Brazilian who came as a number 10, but he was playing in no more than 10 square metres and defenders were finding it too easy to mark him. I had to fight hard to convince him to play as a centre-forward, where he was much more dangerous because of his quick movements. He ended up being top scorer in both Serie A and the Bundesliga, with Borussia Dortmund.

"everybody in serie a played in a 4-4-2. Creative players like del piero or baggio were used as second strikers"

At Udinese, I also perfected the 3-4-3 system that has made me famous.

I started studying this system after I got sacked by Bologna in 1994. I was unemployed and decided to drive to Barcelona to watch some of Johan Cruyff’s training sessions.

One day, I remember, I was the only person watching the session. Cruyff (below) even gave me a lift in his car. My legs were shaking with emotion.

Cruyff’s Barcelona was also playing this 3-4-3 system – but with a diamond in midfield, and Pep Guardiola dropping as a fourth defender.

With Udinese, I decided to play a flat four across the middle of the pitch, because up front I had three great players in Amoroso, Paolo Poggi and Oliver Bierhoff. I did not want them playing 60 metres from goal or running back. That’s why I decided to deploy an extra defensive midfielder in the starting 11. Basically, we defended with only seven players.

Initially, it seemed impossible to convince the players to adopt this new system. They did not want to change. At that time, everybody in Serie A played with the 4-4-2. Creative players like Alessandro Del Piero or Roberto Baggio were used as second strikers – others, like Gianfranco Zola, did not fit into this system and had to go to play abroad.

To try to convince the players, I proposed a deal. “If, with 20 minutes to go, we are losing, we will switch to a 3-4-3 instead of just crossing the ball into the box.”

They were still not convinced, but they accepted the proposal and, in the end, we managed to get good results.

"the first thing i did at milan was call the senior players: albertini, maldini, costacurta"

My work continued on the training pitch, but the real turning point – for that team and, in part, also for my career – came in April 1997. We played in Turin, against Juventus – the then Serie A leaders.

Juventus were dominating the league, and only seven days before they had beaten AC Milan 6-1 in the San Siro. After 50 seconds the referee, Roberto Bettin, inexplicably sent off Régis Genaux, a defender. Instead of substituting one of my two strikers, I decided to switch to a back three and play with a 3-4-2.

I knew this was very risky. Had we lost by five goals or more, my career as a manager would have been really compromised. But I decided to go for it, and the players showed their pride. We won 3-0, with two goals from Amoroso and one from Bierhoff (below). It was a magnificent afternoon.

The following week, we played Parma away. They were challenging Juventus for the title.

The players were nervous before the match, as they didn’t know which system I was going to choose. When I showed them the 3-4-3 formation on the board, they looked relieved: from then on, they only wanted to play with that formation. We also won that game, 2-0, and Udinese finished the season in fifth place. The club had earned their first, historic qualification for the UEFA Cup.

The 3-4-3 is a very complex system. In Italy, many managers have tried to emulate it, but I don’t think anybody mastered it as that Udinese team did.

After qualifying for the UEFA Cup for two years in a row at Udinese, I felt it was right to go somewhere else. All the big clubs contacted me: Parma, Inter and even Real Madrid. In the end, I reached an agreement with AC Milan.

"weah wanted to play as a nine, but i decided to deploy him on the left. He wasn't keen"

Adriano Galliani, the sporting director, called me in the summer of 1998. At the beginning, I thought it was a prank call.

I knew AC Milan were managed by Fabio Capello, but the team had experienced two very difficult seasons, finishing 11th and 10th in Serie A. One week after that phone call, I went to Silvio Berlusconi’s house. We sealed an agreement in less than 30 seconds.

Milan had very good players, but they were getting old – and neither Arrigo Sacchi nor Capello had been successful. The first thing I did was to call the senior players: Demetrio Albertini, Alessandro Costacurta and Paolo Maldini (below). I told them that I could understand if they had doubts about me. I had never been a great player, and I was going to play a system, the 3-4-3, that they were not used to.

These players were open with me from the start. They said they were almost desperate after two horrible seasons, and agreed to try something different. The senior players were key to motivating the others to follow my advice. For two months we worked hard on the training pitch, so the players could learn how and where to move in the new 3-4-3 system.

That season, we felt no real pressure. We were not playing in Europe and so had more time to train. Lazio was a much stronger team, but with seven games left they thought they had already won the Serie A title. I don’t think they took us seriously, and they took their foot off the gas. When we leapfrogged them in the table, they couldn’t manage to respond.

That Milan team was full of pride. There were many great players, like Maldini and Costacurta, who wanted to show they were not at the end of their careers.

Maldini could not manage to cover the whole left flank any more. I told him not to worry and to focus only at being a great defensive left-back, which he had always been. I wanted him to push up to the halfway line; if we were losing, I asked him to attack more. That season, he contributed with a goal and a couple of assists.

"back then, ac milan wanted to win playing good football. Inter were all about the results"

On the other hand, Costacurta struggled if he had to run backwards, because he had lost a bit of pace. He was tactically astute, though, so I told him not to worry about chasing long balls and just block what was in front of him. I gave him a smaller area to cover and, in the end, he was outstanding. He could read the game so well that he looked like he was playing while smoking a cigar!

I did not have a great relationship with George Weah (below, left). We respected each other, but we simply didn’t see things the same way. He wanted to play as a number nine, but that summer Milan had signed Bierhoff. I had not asked the club to sign him – Capello had already signed him – so when I arrived and found him there it was of course a nice surprise for me.

Obviously, I could not ask Bierhoff to play on the flank, so I decided to deploy George on the left. There, he had 30 metres in front of him – and, with Andrés Guglielminpietro behind him, he didn’t have to run after defenders. He wasn’t keen on the new role, but he was very effective when cutting inside on his right foot.

At Milan I also gave opportunities to young players such as Giuseppe Cardone, Lugi Sala and Christian Abbiati, but my biggest regret there was Christian Ziege.

I tried to convince Ziege to play as a wing-back. I was sure he could have been great in that role. He had the technical ability of a number 10 – a great left foot with which he could score goals and provide assists – but he could also run up and down for 90 minutes. He never fully accepted the idea of not playing as a left-back, however, and after leaving AC Milan he didn’t have a great career.

After Milan, why Inter? Easy. I’ve always been an Inter Milan supporter. When I was young, Tarcisio Burgnich, the defender, had been my idol.

In 2003, Massimo Moratti sacked Héctor Cúper and offered me a two-year contract.

"i've always looked at what players can give on the pitch – not their history"

I started very well, but then I lost one of my key players, Francesco Coco, who was playing well as left wing-back. Coco was key in my 3-4-3, but he had to undergo surgery and was out for the rest of the season.

We had a good team though, with Christian Vieri, Adriano and Álvaro Recoba among others, and in the end we managed to qualify for the Champions League. But Moratti had already decided to sign Roberto Mancini as the new manager.

I believe the two Milan clubs were different back in those years. AC Milan were keen on winning by playing good football and had a strong tradition in this sense. Inter, on the contrary, were all about the results. They had not won the league for many years; that’s probably why they were focused just on winning as many games as possible.

I completed my own ‘Big Three’ in Serie A when I joined Juventus in 2010 (above). It was a similar situation to the one I had faced at AC Milan. The team was full of very good players, but many of them were getting old.

I did the best I could, and was about to extend my contract, but then Andrea Agnelli replaced John Elkann as chairman and brought in a new manager, Luigi Del Neri, at the end of the season. Even with Del Neri, the results did not improve – Juventus finished seventh in Serie A, as they did when I was in charge.

I have always found a way to adapt. Obviously, when I did not agree with chairmen or football directors, we ended up going in different directions.

But I have always focused on coaching the players, not the chairmen. I've never phoned a chairman to complain, but I’ve taken calls from those who wanted to suggest the line-up. I have always treated everyone with the maximum respect, and demanded the same from my players.

"i surprised everyone with my decision to go to japan – even my wife didn't believe me at first"

Perhaps the Italian media did not like the fact I didn’t give them information about my line-ups before games, but I always preferred to be honest with my players. At all of those three huge clubs, I always had a good relationship with my players – apart from some of the older ones, who wanted to play because of what they had achieved in the past. But I’ve always looked at what players can give on the pitch, not their history.

I believe that, as a coach, I’ve always got the best results when taking charge of a team at the beginning of the season: at Riccione, Baracca Lugo, Venezia, Cosenza, Udinese and Milan. At the other clubs, when I arrived mid-season, it turned out to be more difficult.

But I was always happy, because I was managing in the most important league in the world. At that time, Serie A might not have been the most beautiful league, but it was certainly the most competitive. Everyone wanted to manage in Italy. I received a few offers from abroad, but I was not interested in the money.

The salary certainly didn’t influence my decision to take the job with the Japan national team in 2010. New experiences have always fascinated me, and I was intrigued by the idea of living and working in Japan.

In fact, in Japan I earned less than I had elsewhere. I surprised everyone with my decision – even my wife, at first, did not believe me. I went there knowing nothing about Japan and their football culture, but it was an extraordinary experience.

We won the Asian Cup in 2011 (above) and we went unbeaten for a record 18 games.

"after 40 years as a coach, i am able to reflect. if i could go back and do it all again, i would"

I didn’t speak the language, but I was still able to demonstrate my ideas on the training pitch. The players were also very talented – many went on to play in Europe.

I fell in love with that group of players – we still text each other often – and I was really impressed by the respect and politeness of the Japanese people. I really felt that they loved me. They were four unforgettable years.

Of course, I have learned many things from my many experiences in football – but I always like to change and try something new. Every player is different from another, and every team is different too. That’s why being a football manager is such a fantastic job.

I am not an egotist, though. I like to share every objective and success with my colleagues and the players.

All the results my teams achieved have come through work and sacrifice, and I always believed in the qualities of my players. I believe I’ve been good at convincing many players to follow my ideas, and approach football in a less conventional way.

Now, after 40 years as a coach, and coming back home to Cesenatico, I am able to reflect. If I could go back in time, I would do everything that I did again.

I always wanted to try to win, even in the most adverse circumstances. And I always played with three up front, even away from home. I was always on the front foot.

That’s who I was as a manager.

alberto zaccheroni