antonio conte

Tottenham, 2021–2023

The last time Antonio Conte replaced the manager who replaced José Mourinho, he led his new team to the title in his first full season in charge. Tottenham, after the reign of Nuno Espírito Santo, may have considerably lower expectations than Chelsea did when Conte was recruited in 2016, but the Italian returns to London with a proven track record of transforming underperforming clubs and their leading players. Indeed, it was Conte who in 2012 delivered Juventus’ first title since the Calciopoli scandal, and who laid the foundations for their dominance of Serie A over the following years.

After leading Italy at Euro 2016, Conte, then 47, impressively inspired Chelsea to the 2017 Premier League title, but hist most recent position at Inter Milan represented his greatest challenge, largely owing to Juventus' strength. During 2019/20, Inter challenged for the title and were runners up in the Europa League, demonstrating significant progress, but as fierce a competitor as Conte is, he demanded yet more. He achieved his goal in the following season, ending Juve's run of nine successive titles by leading Inter to their first in 11 years.

Playing style

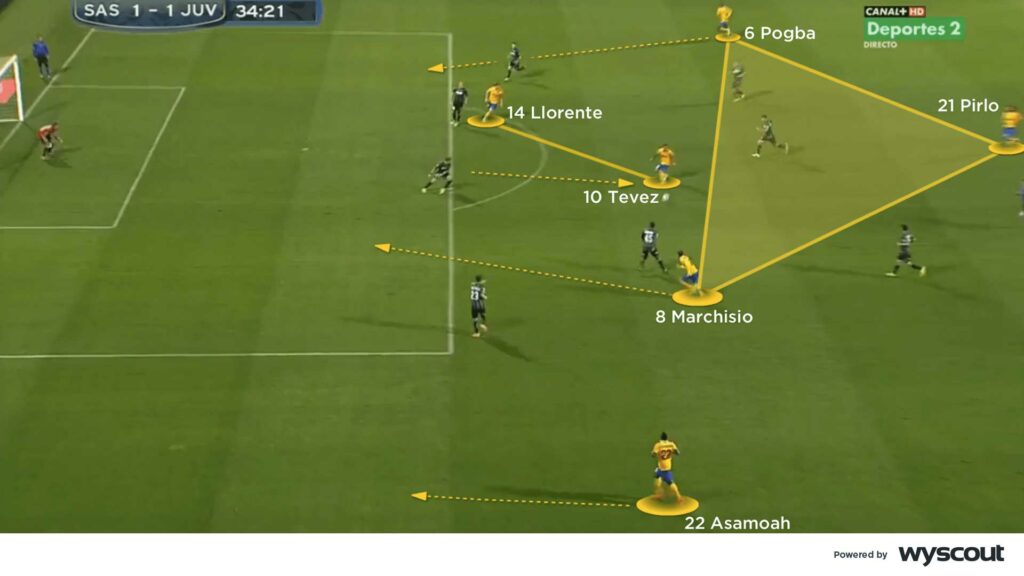

Perhaps the greatest adaptation in Conte's approach took place while he was at Juve, where his preference for a back four was replaced by the in-possession 3-1-4-2 his other teams – Chelsea excluded – have since used. Arturo Vidal, Claudio Marchisio and Paul Pogba offered direct, penetrative attacking runs from midfield (below), and Marchisio and Vidal were regular goalscorers, making forward runs ahead of Andrea Pirlo, who operated from defensive midfield.

As was the case when he managed Italy and Inter, Juve also regularly played passes around the corner that involved the deepest midfielder moving towards possession and bending a first-time pass over the opposition's defence and into the space behind their central defenders. Those passes are complemented by a front two operating on different lines – one to draw a central defender out of position, the other to run on to the pass in behind and, potentially, into a one-on-one against the other central defender.

Italy's 3-1-4-2 was significantly more direct. They lacked a ball player of Pirlo's calibre at the base of midfield and they also had less technically gifted attacking midfielders. So, Conte encouraged his wing-backs to adopt more advanced positions and create overloads with the attacking midfielders, who made forward runs into wide positions. Their front two also remained as advanced as possible for as long as possible, complementing that direct approach and discouraging the opposition's central defenders from moving to assist the underloaded full-backs.

At Chelsea, Conte instead built a successful team on a 3-2-4-1 formation that featured Diego Costa as their lone striker, supported by narrow inside forwards – two of Eden Hazard, Pedro and Willian – and two wing-backs in front of a double pivot. Individually, those defensive midfielders combined with a wider central defender, wing-back and inside forward to create a diamond that encouraged the wing-back to remain wide. César Azpilicueta’s advanced positioning as a central defender strengthened Chelsea's defensive transitions – when they otherwise would have been vulnerable – and provided another proven ball player for the curved passes Conte demands. During 2017/18, Álvaro Morata particularly relished those passes.

Regardless of that shape inspiring Chelsea to the title, his return to Serie A with Inter involved Conte reverting to his 3-1-4-2 or 3-5-2. Their wing-backs – Ashley Young was among those recruited – combined with a wide-moving attacker or forward-moving attacking midfielder, or sought to beat defenders one-on-one and then deliver from a wide position. Their defensive midfielder was instead the one playing the set pass, and in a further adaptation the wing-back clipped the ball forwards towards one of their front two – often doing so having cut infield on to his stronger foot, in Young's case.

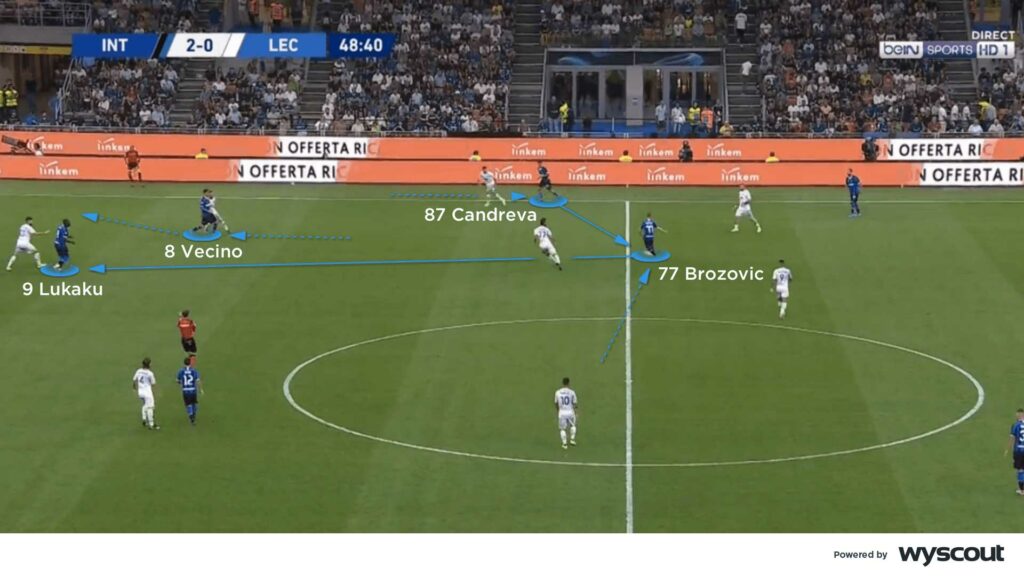

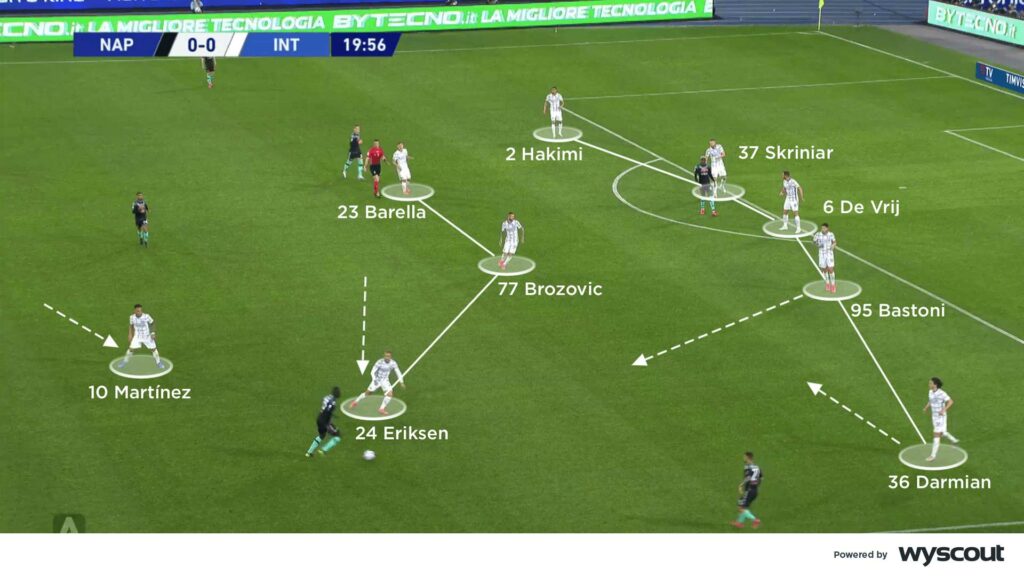

The versatility of Romelu Lukaku and Lautaro Martínez also proved a strength. Both are capable of holding the ball up or running in behind, and therefore complement each other when operating on different lines. There were also occasions when Alexis Sánchez was used in a front two to withdraw into a deeper position, and others when a double pivot was used behind a number 10 – Sánchez or Christian Eriksen – supporting their front two. Marcelo Brozovic was usually the defensive midfielder instructed to play line-breaking passes (above) in their more familiar shape, and two of Nicolò Barella, Matías Vecino, Stefano Sensi, Roberto Gagliardini and Vidal made forward runs from central midfield to combine with those in more advanced positions.

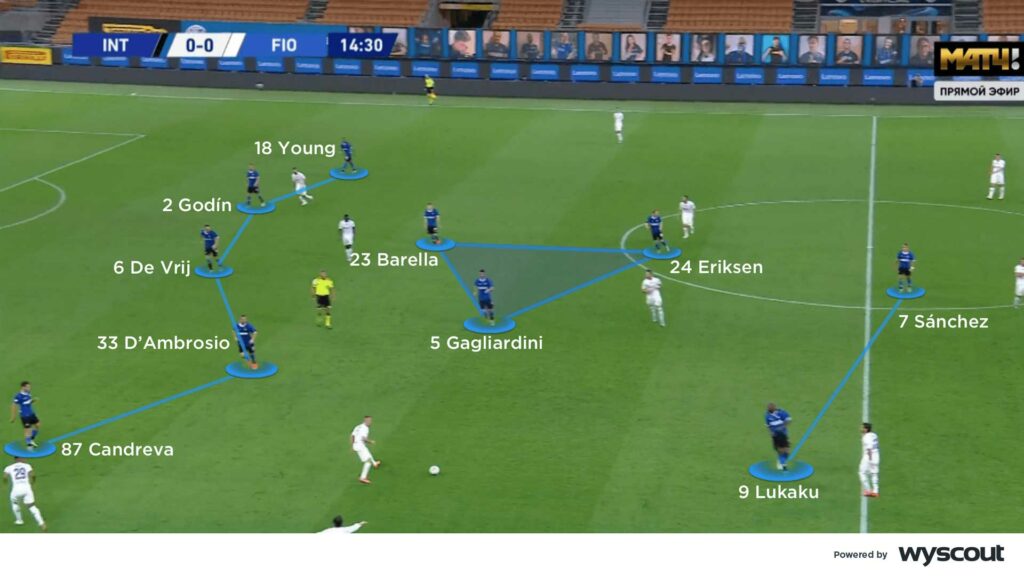

That approach evolved during 2020/21 (above). While one of their front two – most consistently Lukaku – continued to move short, retain the ball and link with those making runs, their wing-backs made penetrative runs through the centre of the pitch. Where for so long in Conte's teams those runs were mostly made by their attacking midfielders, on the occasions it was instead their wing-backs doing so, their central midfielders remained compact and in a position from which to potentially apply a counter-press. Even if they didn't immediately do so, the numbers they offered there could delay opponents until the wing-backs could make recovery runs.

By running into different positions, Inter's wing-backs could deliver crosses from new angles and therefore increase the variety they offered; they also preserved Conte's favoured front two by one making runs towards goal either striker had withdrawn into a deeper position. Their presence there meant Inter's attacking midfielders increasingly operated outside the penalty area and, should those wing-backs be more central, drifted wide.

Defending and pressing

The introduction of a back three at Juve meant that Andrea Barzagli, Leonardo Bonucci and Giorgio Chiellini consistently featured in central defence, and gave Conte's attacking midfielders the freedom to make regular forward runs. When defending they reorganised into a particularly compact and organised 5-3-2 that gave opponents minimal space to attempt to play through. Conte's Juve proved particularly difficult to penetrate. If ever they looked vulnerable, it was after their attacking midfielders and wing-backs had made those aforementioned forward runs, and opponents were positioned to quickly counter. With only a single pivot offering protection in midfield, and an occasional lack of agility in their front two that meant they struggled to counter-press, even a back three as experienced as theirs could become stretched.

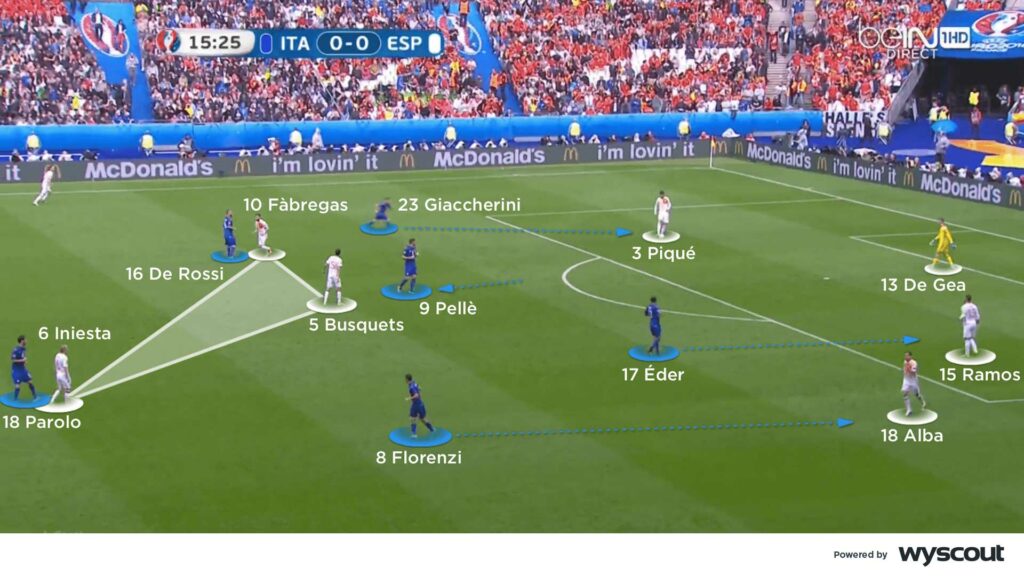

A 5-3-2 mid-block and, when necessary, a lower block, have so far proved Conte's most successful defensive approaches. His front two are used to screen attempts to build play through the centre, forcing opponents to take play wider, and in the case of Italy at Euro 2016, limiting the potential of high-quality opponents like Toni Kroos for Germany and Sergio Busquets for Spain. A further effective trait in his mid-block is the pressing traps that follow the front two forcing play wide; the three central midfielders shift across, covering the inside channel and advancing towards the opposing full-back. With Italy, Daniele De Rossi superbly prevented access into the attackers, and their wing-backs effectively limited space in the wide areas. Chelsea, and then Inter, regularly applied the same high press occasionally seen with Italy (above).

At Inter, the 5-3-2 they often defended with (above) sometimes became a 5-2-3 in which one striker worked to limit access into the opposing single pivot while the other striker and an attacking midfielder pressed the opposition's central defenders. The wing-backs advanced to engage with the full-backs opposite them – even if that risked a three-on-three in defence because Conte was confident in the aerial strength of his central defenders. If his attackers could force the opposition into direct balls, the defenders often won the ball back.

Though Chelsea's defensive shape was a 5-4-1 mid-block, they were less vulnerable at defensive transitions because they had a double pivot in front of their defence. They also pressed with greater aggression in midfield; their back five and their additional midfielder gave them the potential to press all three central lanes, which protected against opponents seeking to operate between the lines. When one of their wider central defenders advanced to a position alongside their double pivot, the inside channels were also covered when possession was lost in the attacking half.

Inter had Serie A's best defensive record in 2019/20, through defending with what was typically a 5-3-2, but until 2020/21, as with Juve, there were occasions they were exposed at the point of a defensive transition. When their wing-backs and attacking midfielders advanced, their defensive midfielder sometimes struggled to protect the centre of the pitch. Given Inter's wider central defenders could be vulnerable when defending one-on-one against a fast and capable attacker, Conte experimented with a double pivot that featured one advancing to add to attacks alongside their number 10.

When they were defending with a mid or lower block, their central midfielders worked to provide defensive support in wide areas; the closest striker screened access back infield; and their wing-backs attempted to force play wide. If they forced them to recycle possession and switch play, Conte's team adjusted to do the same on the opposite side of the pitch. Their wider central defenders pressed out from defence (above), and their attacking midfielders were free to move out wide to press, with the wing-backs having moved infield to track any forward runs, ultimately maintaining the numbers Conte demands in the centre of the pitch.

In the same way their wing-backs' movements enhanced their attacking potential, they also made Inter's defence more resilient. Their back three and defensive midfielder received greater support because their attacking midfielders' positioning meant that they were considerably less exposed, negating many of the weaknesses both Inter and Juve previously demonstrated during moments of transition.

A further potential change existed in their approach to pressing high, when only one of the two wing-backs advanced and the three central defenders drifted across to form a back four. Their midfield three moved across so that one operated similarly to the advancing wing-back. The remaining two then formed a double pivot and, for brief periods, Inter therefore pressed with a 4-4-2 (above). From this shape, they worked to keep the ball to one side of the pitch, and their front two stopped passes into the centre of the pitch before pressing their opposing central defenders and goalkeeper.