jose bordalas

Valencia, 2021–2022

José Bordalás spent more than 20 years as a coach before reaching La Liga in 2016, when he led the unfashionable Alavés back into Spain's leading division after a 10-year absence. Twenty-three days after inspiring that promotion, he was then ruthlessly sacked – the opportunity he had sought for so long was being taken from him before he even had a chance to test his coaching and man-management abilities against Spain's finest.

"It was unexpected and it was disappointing but it also served to encourage me to bounce back, to keep on growing and that has been one of my virtues – never to be down for too long," Bordalás said, when revisiting his departure. "When I got the offer from Getafe they were already eight or nine games into the campaign and in the relegation places." Getafe, of the Spanish capital of Madrid, had been relegated from La Liga during the previous season but, following Bordalás' appointment, made an immediate return when securing promotion via the playoffs and increasingly made such an impression that Valencia identified their manager as the one who could provide them with the stability they have long lacked.

Tactical analysis

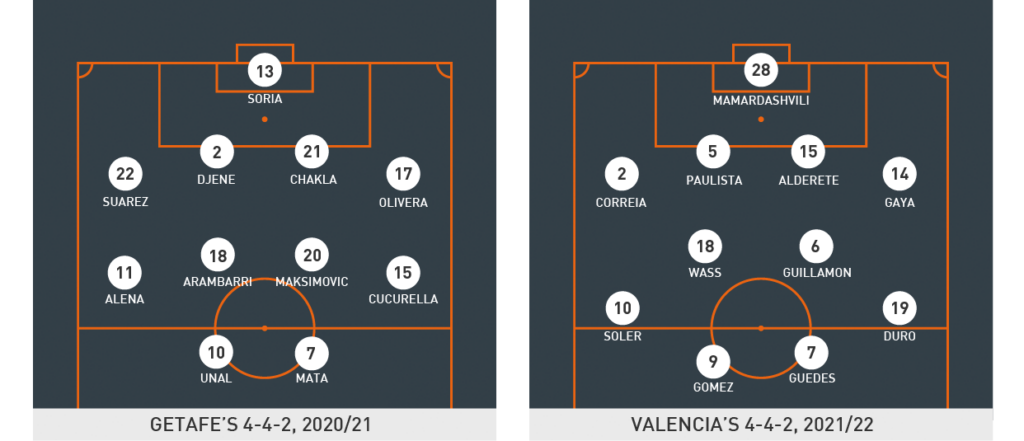

Getafe were widely recognised as being committed to the most organised of 4-4-2 formations. They favoured a direct approach that relied on them complementing their positional discipline with winning possession either from a direct ball, or by collecting the resulting second or third ball. Players were encouraged to be close to those balls as a unit, and thus in position to press and regain possession if necessary.

They were capable of producing link play to combat opponents favouring a lower block, but doing so was not their favoured form of attack. They instead looked to advance from defensive transitions with speed and intensity while prioritising the spaces in behind opposing central defenders, or between central defender and full-back, and playing towards their front two.

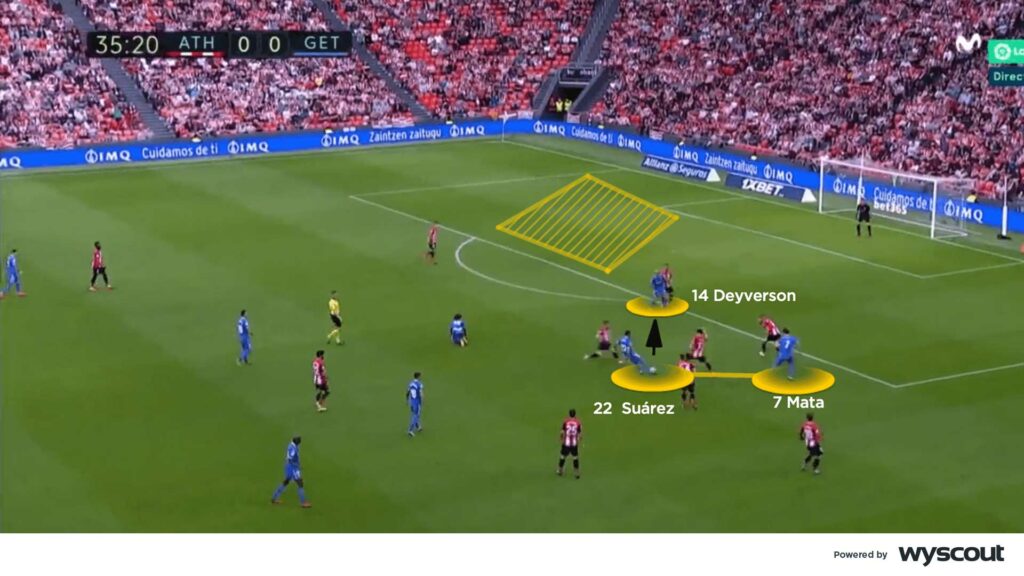

Nemanja Maksimovic and Marc Cucurella were prominent among those supporting those attacks. Cucurella, particularly, sought to play crosses into the penalty area towards the front two of Jaime Mata and Jorge Molina; Ángel and Robert Kenedy also excelled in attacking those same spaces. Deyverson similarly contributed by winning possession before controlling it and finishing, or by receiving the ball (above) and then retaining it until teammates arrived to offer support.

Getafe registered the lowest ball possession in La Liga during 2017/18 and 2018/19, and remained among the lowest in the two following seasons until Bordalás' departure. When regains were made they quickly targeted the front two that featured one striker threatening on the shoulder of the deepest positioned defender and the other being more withdrawn to link play, having also been contributing in central midfield when they were without the ball. Their strikers regularly recorded Getafe's highest number of assists because of their ability to combine without supporr from the midfielders behind them, and their movements meant regular direct forward passes were played. Only Eibar recorded more long passes than Getafe in La Liga during Bordalás' four seasons as manager.

That their front two attacked closely together to compete for aerial balls and target the second phase of play regardless meant spaces emerging around them for, most commonly, Getafe's wide midfielders to run into and support from, though when the team's overall priority was to preserve their sense of balance (above).

It was from towards the left that Mata and Molina were most consistently targeted; Alan Nyom, a natural full-back, often featured as their right-sided midfielder, and proved limited in the attacking half. From the left Cucurella regularly attacked around the outside of their opposition and then delivered crosses, or played quick and incisive forward passes, and Amath Ndiaye dribbled and attacked one-on-one, but his contributions were mostly unlike those of his teammates.

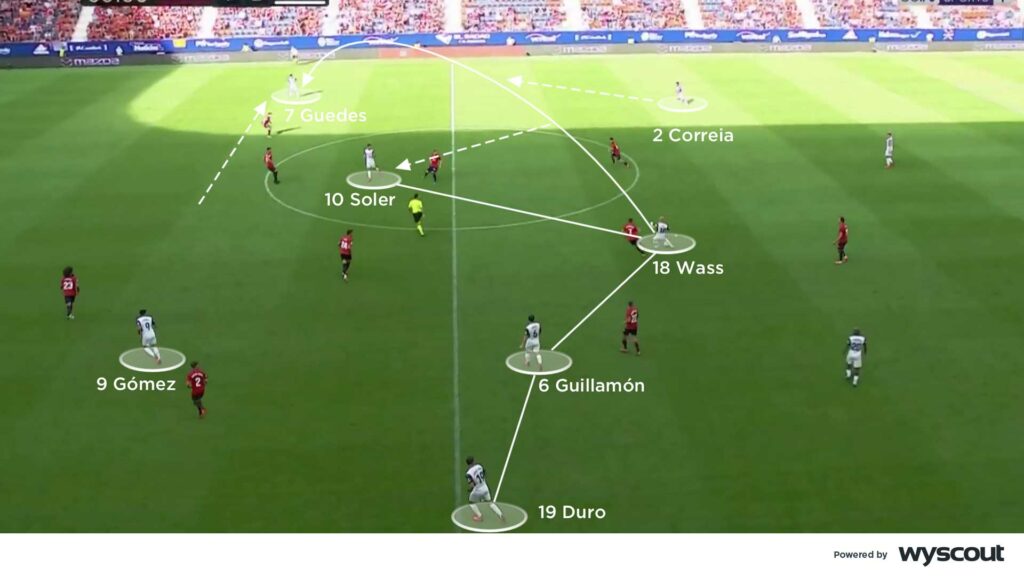

Valencia have so far also placed an increased emphasis on playing long passes and attacking crosses, and have done so from a 4-4-2 led by Maxi Gómez and Gonçalo Guedes (above), who has been converted from a left-sided forward. Among those long passes are those played into wide territory and those directly into their front two – like those played by Getafe. Given only Gómez, and not Guedes, is authoritative in the air, those sent wide have often been significant in Los Che breaking forwards from their defensive block.

Guedes' presence ensures more rotations than had been witnessed at Getafe; he regularly drifts wide from a central starting position from which he supports from behind Gómez, and when he does so one of their wide midfielders moves infield to replace him centrally and preserve their fronr two. There are also occasions that those wide players move infield to encourage overlaps from and ultimately the creation of overlaps with the full-back behind him – José Gayà and Dimitri Foulquier have, like Guedes, regularly delivered crosses into the penalty area from wide territory.

Defending and pressing

Getafe's commitment to a team approach – their organisation, conditioning and cohesion – involved a collective effort to press and then regain possession. Their entire XI commonly defended in a mid and low block, particularly during home fixtures, and therefore operated with a very high tempo that meant leaving few spaces for opponents to penetrate through their structure or to build attacks in wide positions. If an opponent succeeded in doing so, Getafe responded by again attempting to reduce the relevant spaces before prioritising regaining possession with numbers and defensive overloads.

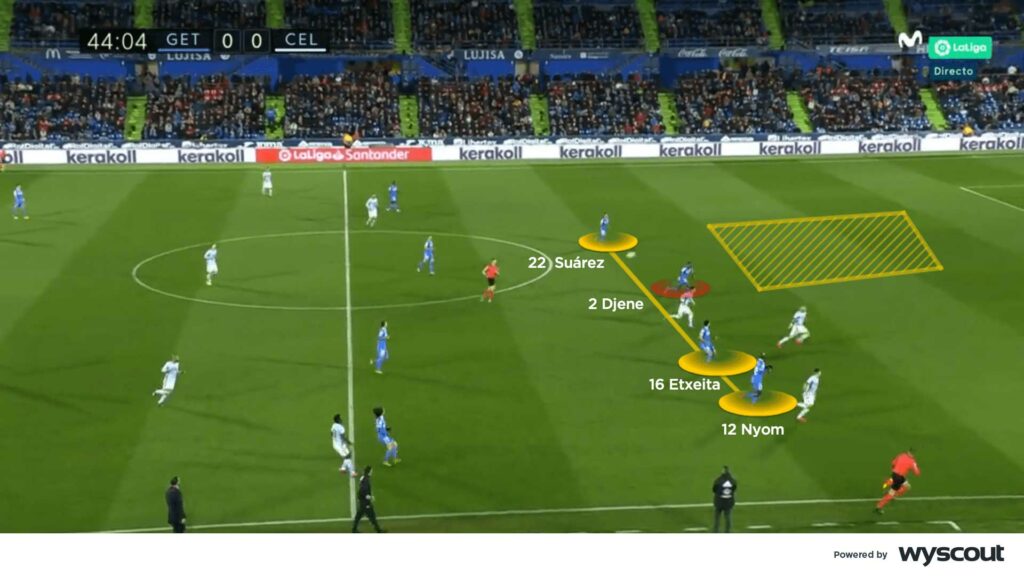

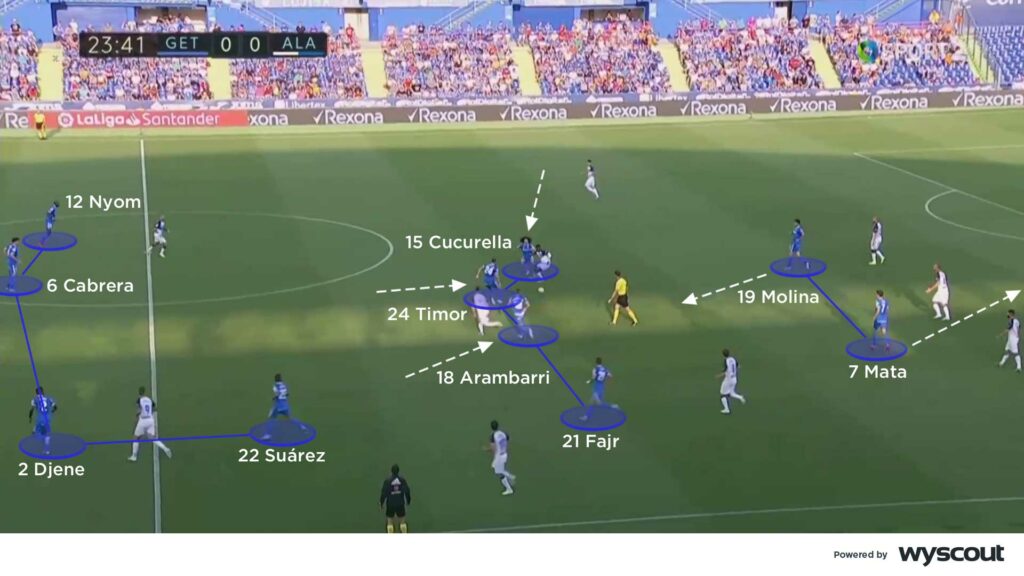

If there was a consistency to their approach in the period after Bordalás' appointment, there were also tweaks that demonstrated it was subtly evolving. Throughout 2019/20 their defensive block was positioned further up the pitch than had previously been the case, largely because of the security offered by the presence of Djene Dakoman, whose athleticism and positional awareness made him capable of correcting imbalances that may have existed in their defence (above). That ability to recover was complemented by so few mistakes being made in central midfield, where Maksimovic and Mauro Arambarri held their positions and encouraged those around them to continue pressing in the attacking half.

What was often the narrowest of midfield lines (above) worked hard, from the same out-of-possession 4-4-2, to shuffle across the pitch with a similar level of organisation and discipline seen with Atlético Madrid under Diego Simeone. One of their front two pressed from behind the ball to support in midfield and potentially allow his teammates to recover their desired balance against opposing midfield threes, and to provide an additional angle of pressure to the ball. Their wide midfielders, similarly, moved infield to support the aggressive press Bordalás demanded in central territory, and often pressed slightly ahead of the two central midfielders between them because of the latter's desire to protect the spaces between the lines and their central defensive teammates. That their front two remained brace to make forward runs, and in so doing drew opponents with them, after regains were made often enhanced Getafe's ability to secure the ball.

When they were adopting a lower defensive block their strikers worked back, most regularly to goalside of the opposing defensive midfielders, in turn freeing up their central midfield teammates to withdraw into deeper territory and their wide midfielders to tuck infield and cover spaces in the centre of the pitch. In the event of opponents attempting to progress through central territory, Getafe's defensive block retreated further, and they applied an aggressive individual press intended to make regains instead of force possession elsewhere. Should the ball travel wide, their intensity regardless slightly reduced, and was only heightened again if the ball reached their defensive third, at which point their full-back would aggressiely advance, with the support of a wide midfielder, and their central midfielders worked to cover spaces infield and potentially replace the relevant full-back in their defensive line.

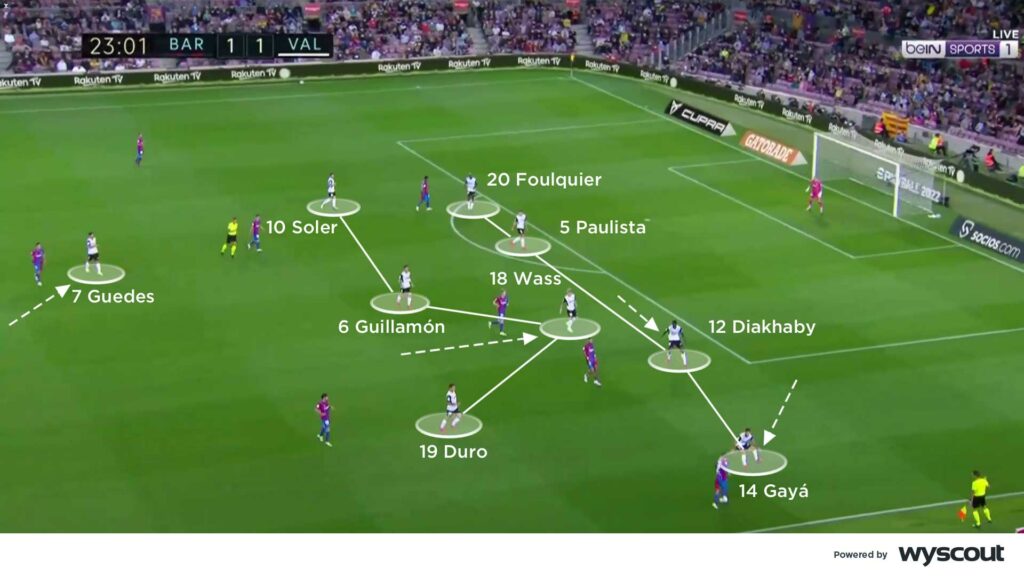

Those same mid and lower blocks, and that out-of-possession 4-4-2, have since been adopted by Valencia. Daniel Wass and Hugo Guillamón have been influential in applying the aggressive pressure Bordalás seeks in central midfield, and in protecting the central spaces – potentially via withdrawing into their defensive line – and the overall narrow defensive block that exists contributes to possession being forced wide, where Valencia's full-backs then engage.

As was also often seen at Getafe, Valencia's front two adopt staggered positions from which to defend around their opposing defensive midfielder, but unlike at Getafe there have been occasions when one player has remained advanced, even as a low block has been adopted. Gómez has, in those circumstances, represented their direct target when they are countering forwards from deep territory, and Guedes has provided support in central midfield but remained capable of moving wide and to potentially pursue spaces in behind an advanced full-back, in turn making his wider runs an alternative target when they break.