jose mourinho

Roma, 2021–

Confirmation of José Mourinho's return to Serie A as the successor to Paulo Fonseca represented a return to the football culture in which he experienced his greatest season in football in 2009/10. Then the manager of Inter Milan, who he so memorably inspired to the treble of Serie A, Italian Cup and Champions League, it was his new team Roma – led by Claudio Ranieri, his predecessor at Chelsea – they beat in the final of the Italian Cup and to the Scudetto by two points.

Back in Italy following three successive positions in the Premier League, at Chelsea, Manchester United and Tottenham, Mourinho is also repeating a move he made the first time he left England – that following his departure from Chelsea in 2007. With Juventus, Inter and cross-city rivals Lazio also rebuilding after changes of manager, in perhaps the most tactical football culture of all, his expertise will again be given a significant test.

Playing style

At Tottenham, Mourinho inherited an attack that, beyond Son Heung-min, offered the influential Harry Kane too little support, and in which Christian Eriksen and Dele Alli contributed minimal defensive cover. That Spurs’ full-backs – then defensively vulnerable – were therefore regularly exposed meant that they too rarely posed an attacking threat during moments of transition, too often leaving Kane frustrated.

Kane’s effectiveness was such that he warranted being the focal point of an attack, as, under Mourinho, other powerful strikers – Didier Drogba, Diego Costa and Romelu Lukaku prominent among them – had been. It was strengthening their ability to attack during transitions that represented the most influential change the Portuguese oversaw.

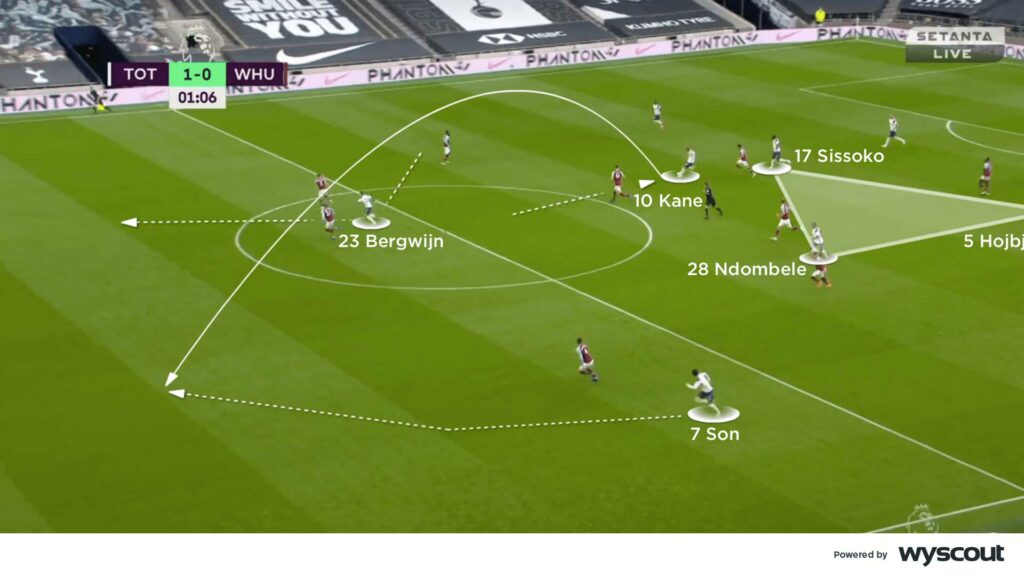

Kane long provided intelligent and effective link-up play, often via midfielders in Eriksen, Alli, Son, Érik Lamela, Giovani Lo Celso and more moving infield. Under Mourinho he gradually dropped into a deeper, central position, and also sought to provide an option in a wider position, with the intention of continuing to contribute to those combinations. From those deeper areas he was increasingly encouraged to use his superb range of forward passing (above).

His movements also encouraged the wide attackers outside of him to run further forwards, and often to become their most advanced players during attacks, where previously it would have been Kane who remained advanced and Spurs' wide attackers who progressed possession (below). Those movements were also complemented, at a late stage, by them moving infield, having until then offered improved defensive cover in front of the full-backs behind them. Son consistently relished both Kane's ability to play the ball and to retain and secure it until then, often making Spurs' transitional attacks lopsided, but at a time when Gareth Bale promised to gradually offer a similar threat from the opposite wing.

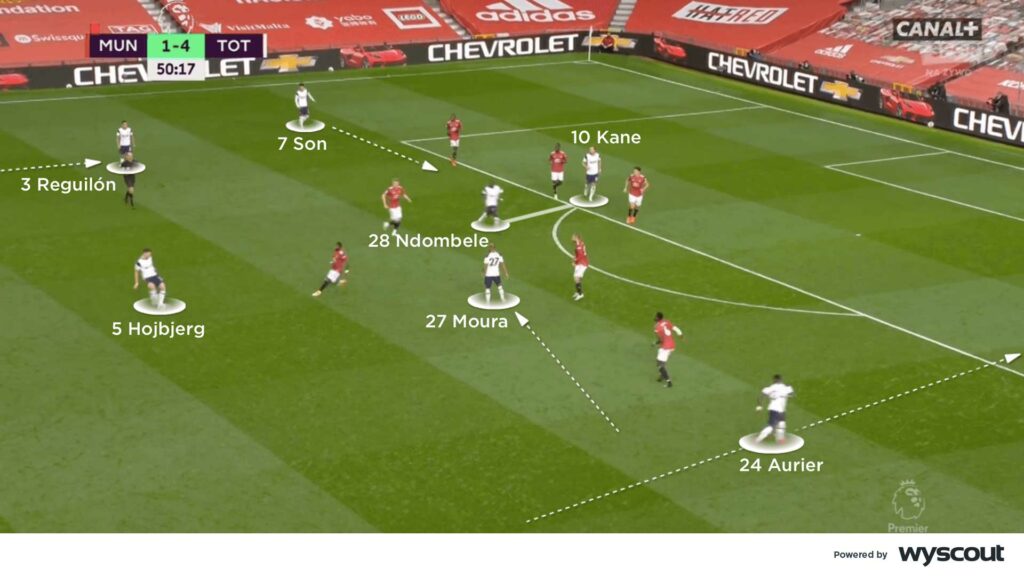

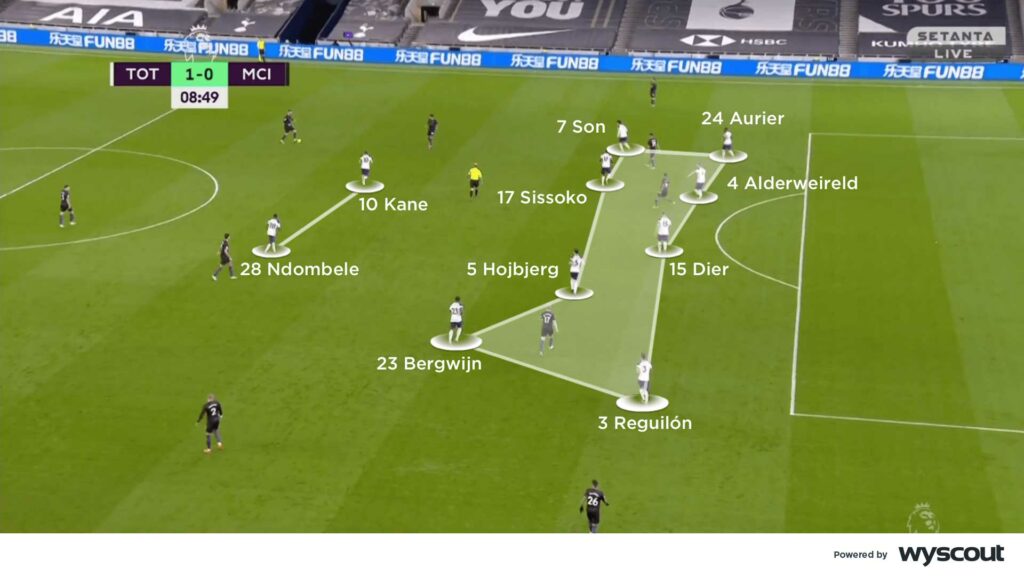

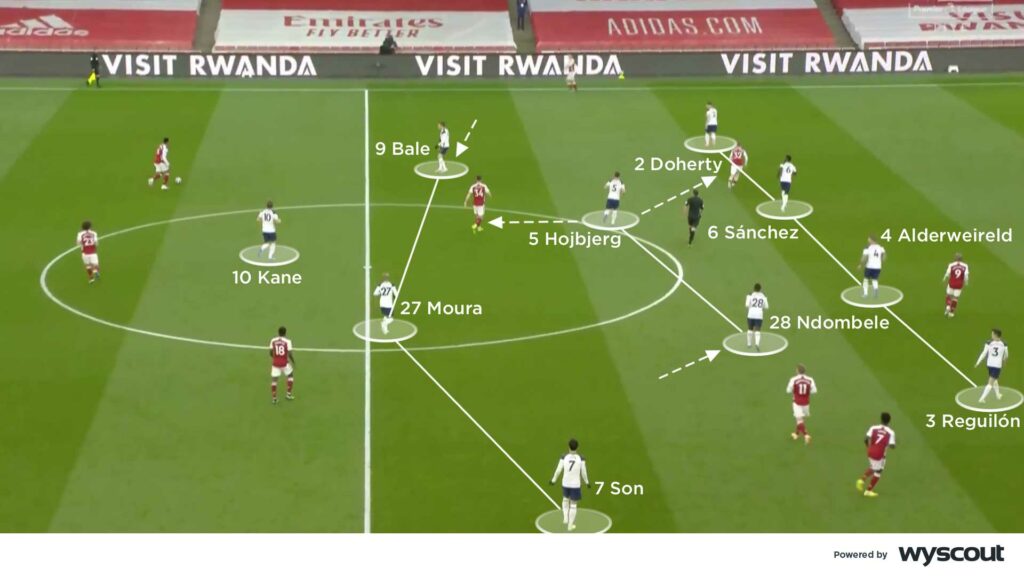

Even with Kane's increasing use as a creator of goalscoring chances, when they were not attacking during transitions, he pursued positions from which to provide the finishing touch. The double pivot that existed at the base of their midfield encouraged Matt Doherty, Serge Aurier and Sergio Reguilón – all fine crossers of the ball – to attack with width from full-back (below) during sustained periods of possession, and largely because of the consistent defensive cover Moussa Sissoko, Pierre-Emile Hojbjerg, Harry Winks and Tanguy Ndombele provided from that double pivot. Ndombele and Sissoko also featured as a third, more attacking, central midfielder, and contributed to a central midfield three that strengthened Spurs' grasp of possession.

Ndombele, from between the lines, replaced the creativity previously provided by Eriksen, whether selected as a number 10 or a more reserved attacking midfielder, and to the extent that Spurs could seamlessly reorganise from their favoured 4-2-3-1 into a 4-3-3, and occasionally even a 4-3-1-2 when Ndombele advanced to alongside Kane. His disguise, and ability to break lines, combined with the movements offered infield by Son, Bale, Lamela, Steven Bergwijn and Lucas Moura, also drew defenders from Kane. His partnership with Kane often resembled that the striker once had with Alli. When it was formed there was less of a reliance on Kane to be their most creative player, therefore giving him the freedom to pursue positions from which to score, and increasing the threat they were posing inside the penalty area.

From within their 4-2-3-1 or 4-3-3, Hojbjerg withdrew into deeper territory to support their two central defenders and encourage their full-backs to advance. If he moved from a double pivot instead of remaining there and seeking to cover from behind their overlapping full-backs, his midfield partner provided protiection at the base of midfield and was supported by their 10. When doing so from their 4-3-3, both attacking central midfielders adapted their positions to support through the inside channels, cover inside of the relevant full-back, and withdrew to closer to their defensive line.

In both structures their width was provided by their full-backs, and their wide forwards moved infield (below) – the right-sided of the two often doing so the extent he operated as a creative link from midfield to attack, and adapted his position depending on whether they were organised into a 4-3-3 or a 4-2-3-1 in which a 10 was already in place. From the left, Son moved infield with the intention of making penetrative runs and those in behind and off-the-ball in an attempt to operate from closer to Kane. Their potency as a combination increasingly meant them being targeted as often as possible, whether via lengthier periods of possession or counters. Together they broke a 25-year record for the most goal combinations in a Premier League season.

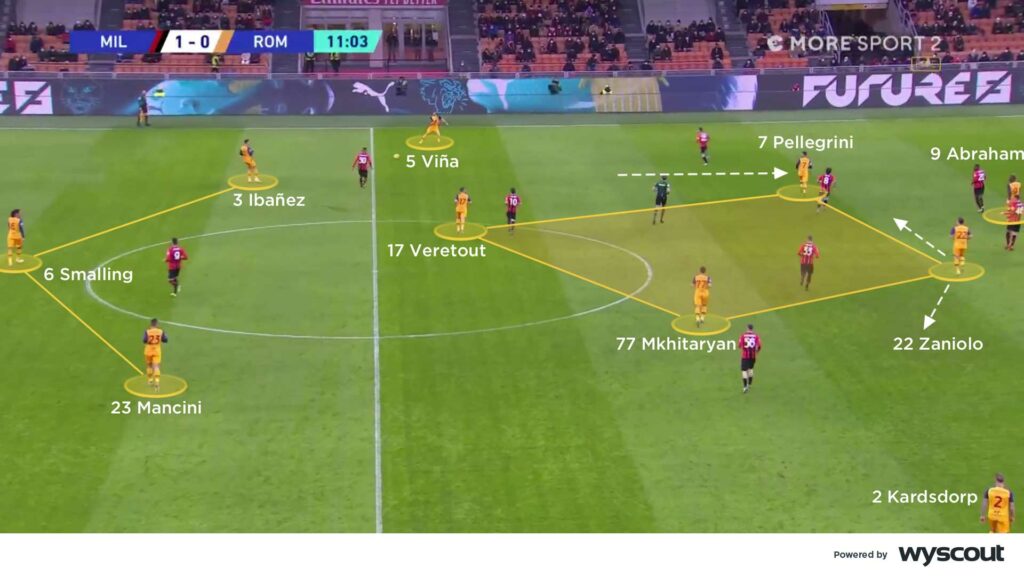

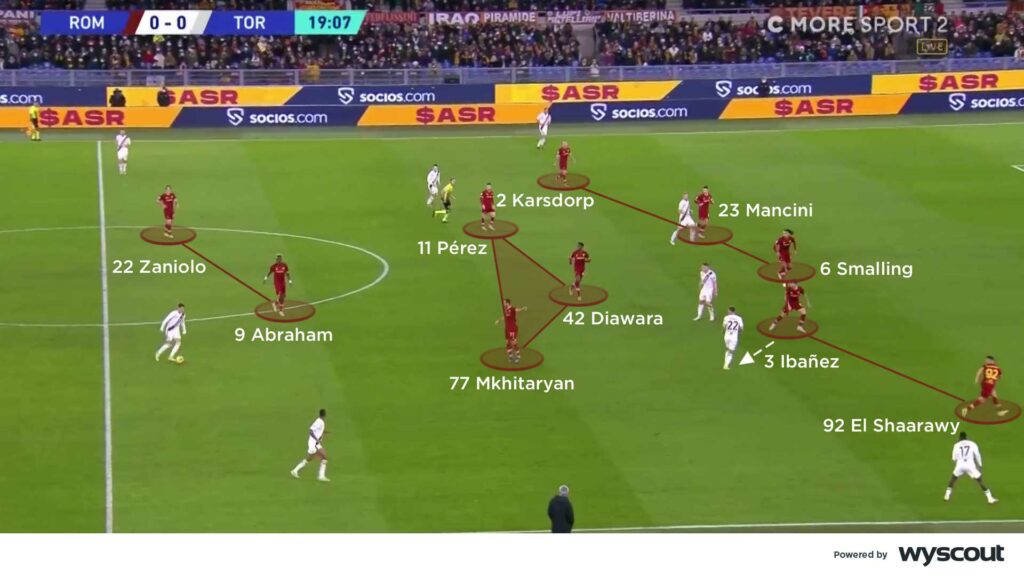

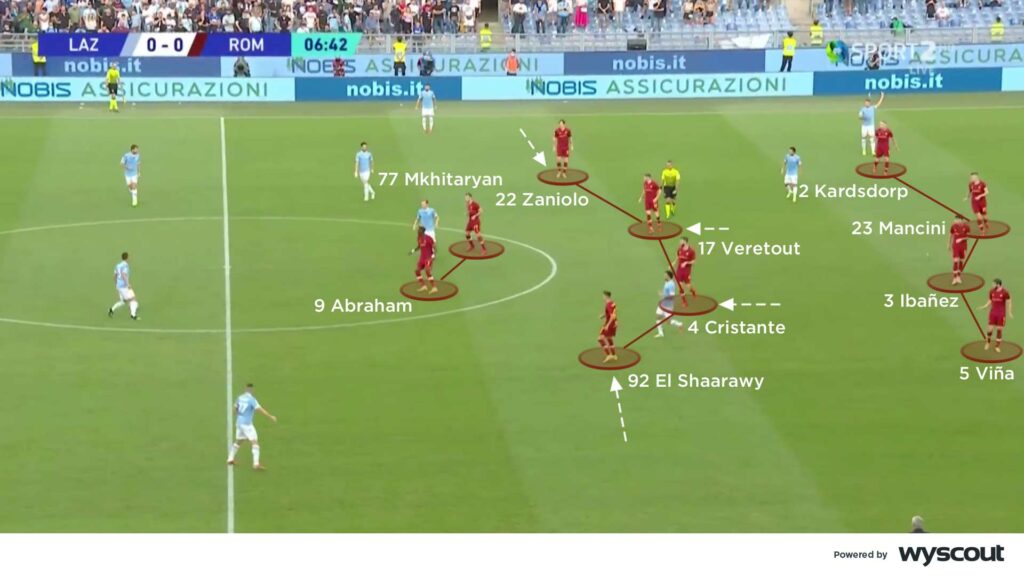

A 4-2-3-1 led by the powerful Tammy Abraham, most commonly supported by Lorenzo Pellegrini, Nicolò Zaniolo and Henrikh Mkhitaryan, has also often since been Roma's favoured system. The double pivot behind them typically adopt wider positions, but ones that regardless invite their full-backs to advance; from the right, Rick Karsdorp provides a regular source of crosses, but their senior left-back Matías Viña favours providing support but fewer crosses, in the knowledge that Jordan Veretout is likely to advance through the left inside channel from the base of midfield and that their left-sided wide forward will move into a central position.

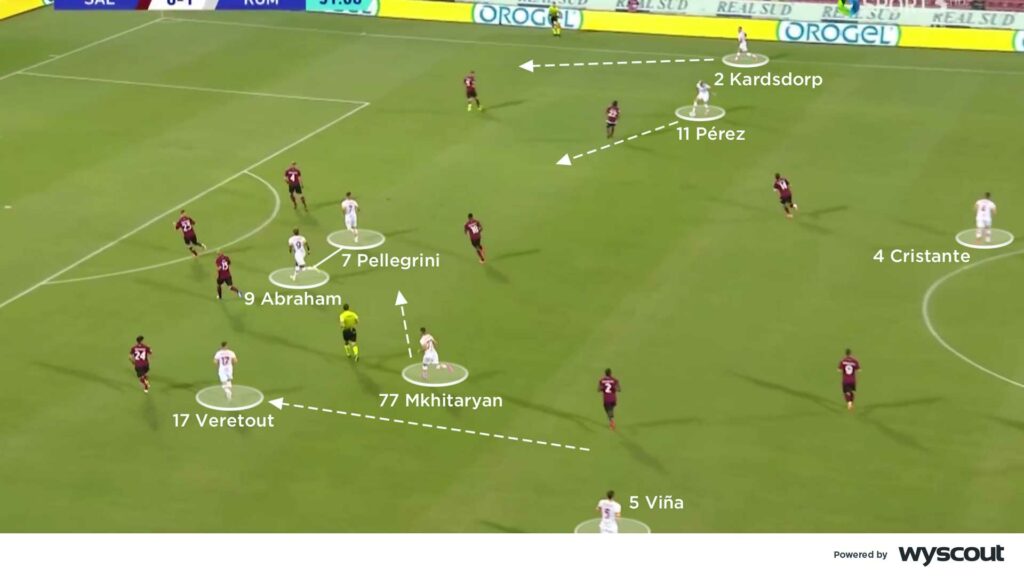

There have also been occasions when Mourinho has favoured a 3-5-2 in which their wing-backs have provided Roma's attacking width – and also the use of a solitary defensive midfielder. Their attacking midfielders advance – particularly when Abraham's strike partner withdraws into deeper territory – and offer fluid rorations that even contribute to the formation of a temporary double pivot, and to a central midfield box (below) led by a 10 seeking to support Abraham.

The willingness of Zaniolo, typically Abraham's strike partner, to move from Roma's attacking line encourages Abraham to remain advanced, occupy opposing central defenders, and then either link into those moving forwards, roll his opponent, or make runs in behind that potentially create space between the lines. When those with more attacking instincts are selected as their attacking central midfielders, there exists an increased presence around their starting striker (below).

Those starting at wing-back also contribute to their attacks, and benefit when rotations in midfield draw their opponents into narrower shapes. Karsdorp, particularly, repeatedly attempts to move into the final third and to deliver crosses to those making forward runs through central territory.

Pressing and defending

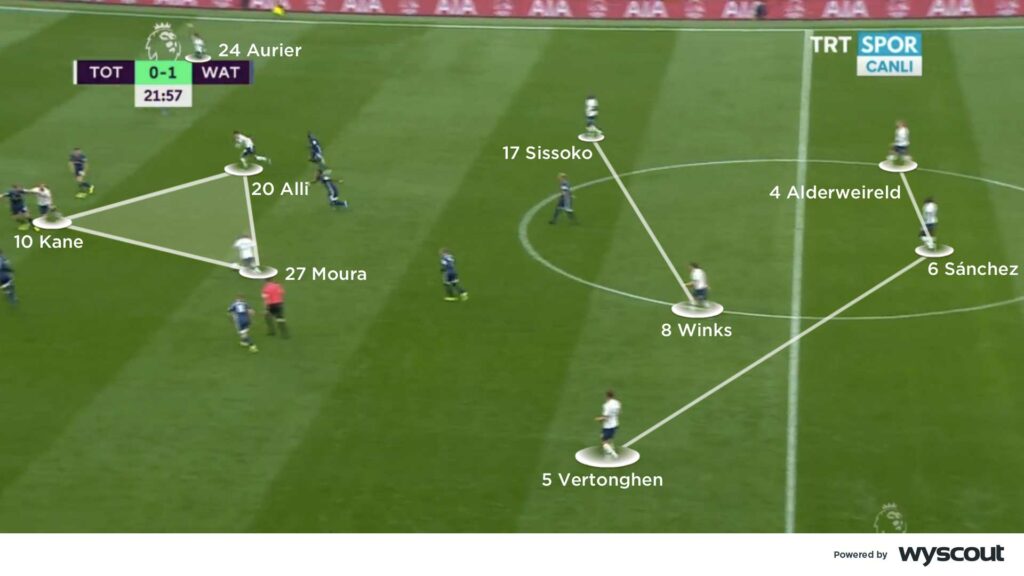

From the start of 2020/21 at Spurs, Mourinho consistently favoured the 4-2-3-1 (above) – built on a double pivot – that brought him such success at Inter, and elsewhere thereafter. The arrival of Hojbjerg from Southampton was particularly key to them doing so. His team were organised to defend with either a lower or mid-block, and largely resisted committing to a high line. The line of pressure between the first and final thirds – their first line of pressure was often progressed beyond – was essential to that; their full-backs advanced to alongside their double pivot, where as a four, their strength when duelling for possession and in the tackle prevented numerous attacks, and ensured that the second and third lines of their structure remained compact.

Not only were their previously vulnerable full-backs offered increased protection through the relationships that were developed in wide areas and that contributed to a press, from small units, being applied, they were conceding fewer goals. The intensity provided by those forming their double pivot, to move and cover the inside channels, proved similarly effective against an opposing double pivot or should an attacker withdraw into midfield to receive. It was also complemented by cover from the wide midfielders and full-backs alongside them, behind the front two of Kane and Ndombele (below) seeking to screen central access and to pressure defenders tempted to move into midfield.

The signings of Doherty and Reguilón were, like Hojbjerg, also influential. Both were more effective than their predecessors at applying Mourinho's favoured, reserved pressing strategy and lower block, and of reacting and contributing when Spurs attacked on the counter. That there were also occasions when he instructed his double pivot to occupy deeper territory to protect the inside channels or even to withdraw into defence – to encourage their wide players to remain more advanced – increased their tactical flexibility. The deep-lying 4-4-2 that that meant they could adopt was particularly suitable when required to defend with a compact lower block for lengthy periods, and previously brought the manager success.

A further consistent theme of Mourinho’s management has long been his ability to adapt the nature of his coaching, and the strategy he pursues, to the players at his disposal. It is perhaps only at United that he did not do so to the same, impressive extent he has previously demonstrated in different leagues and competitions. The aggression of Mourinho’s Porto after losses of possession contributed to so much of their success; their ability to counter-press to negate opposing transitional attacks and then to enhance their own contributed to them dominating domestically and in Europe. In his first spell at Chelsea, ball-winning central midfielders were used to encourage the attacking threat posed by athletic wide players in Damien Duff, Arjen Robben and Joe Cole, and the powerful strikers who were supported by late runners from deeper territory.

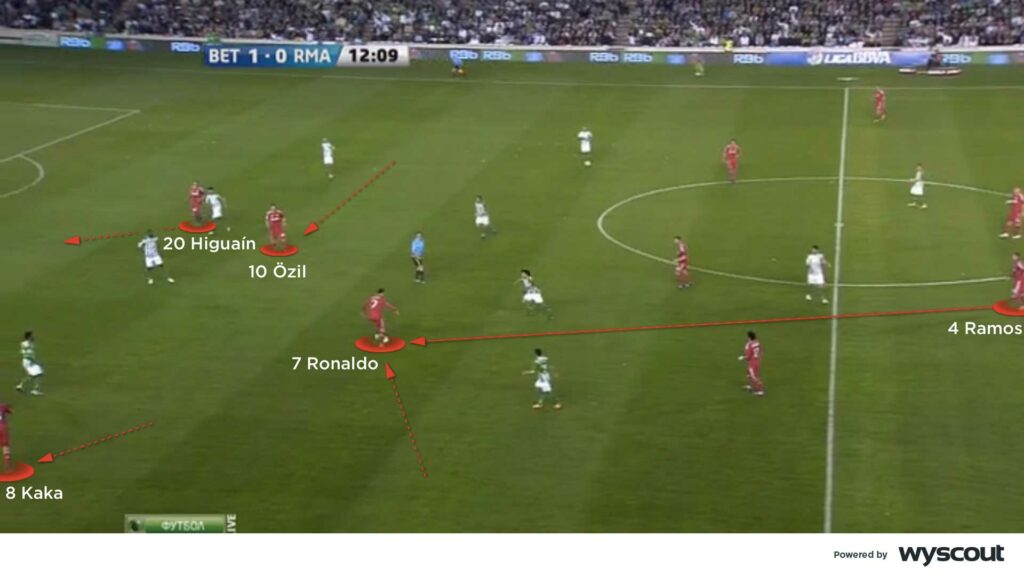

In his two seasons at Inter, Mourinho’s team was built on an extremely organised low block that absorbed pressure for lengthy periods, to mentally and strategically wear opponents down. A fine, experienced defence was coupled with a similarly experienced attack (above); Inter lacked the energy and youth of Porto, and the speed and ferocity of Chelsea, and were therefore incapable of remaining as far forward for as long as those teams once did. Upon leaving Inter for Real Madrid, and inheriting a youthful attack (below), he then developed a transitional team, having just left one at its best when counter-attacking from deeper positions. A peak Cristiano Ronaldo was most consistently supported by Ángel Di María, and one of Gonzalo Higuaín and Karim Benzema.

During his time at Spurs there existed elements from many of his previous clubs. The deep defensive organisation shown against other leading Premier League teams evoked his time with Inter, who were content to remain compact in the deepest of blocks and to convert the few chances they created. Spurs' management of defensive transitions – and aggressive, wider pressure and their desire to protect the weaknesses that would otherwise exist there – mirrored Porto. Similarly, their counter-attacking potential, wider support, and potency when launching into an attack around a focal point was akin to that seen in Madrid.

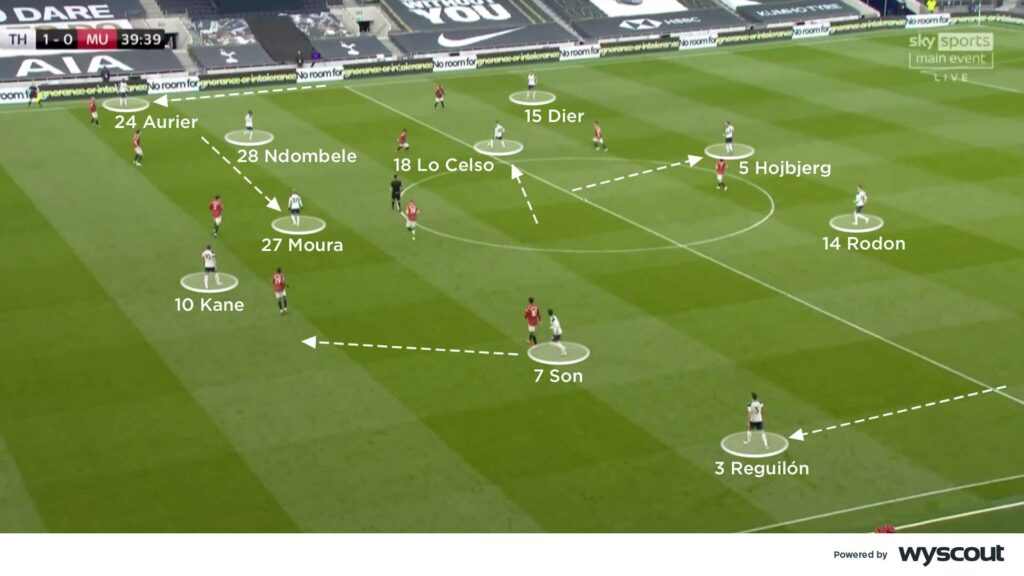

Their continued use of mid and low blocks was complemented by withdrawn midfielders and a particularly deep double pivot that sought to protect the spaces around their full-backs. A 4-2-3-1 (below) was their most common shape when they defended with a mid-block – even when they attacked with a 4-3-3 – and featured wide forwards who moved into narrow positions to cover the inside channels and attempt to force opponents wide where, if they were progressed beyond, their double pivot moved to press.

While supporting the relevant full-backs as they sought to apply pressure and block crosses, the right-sided forward withdrew to contribute in the centre, and the left-sided forward, typically Son, continued to seek to provide a transitional threat, and therefore resisted retreating too far. The striker and 10 covering the central lane also sometimes contributed to the pressure being applied when opponents sought to play through the centre of the pitch, and the 10 travelled further to provide cover if a defensive midfielder was drawn forwards to press; it was when Son was that 10 that he also then moved into positions closer to Kane in an attempt to start counters after regains.

Throughout 2021/22, Roma have been similarly committed to an out-of-possession 4-2-3-1 and mid and low blocks, but one in which their 10 is often deeper than was Spurs' – when not advancing to support Abraham – and in which their double pivot plays from further forwards and their wide forwards track back into the defensive half to support their full-backs.

There again exists a desire to force opponents wide, but the positioning of their wide forwards and defensive midfielders means that they often do so with a four-strong, narrow midfield line, and therefore even occasionally defend with a 4-4-1-1 or 4-4-2, not least when moving into a lower block. It is only when their 10 moves back into central midfield that their midfield line offers similar width to that seen at Spurs. That slightly more space exists between the lines means Roma's wide forwards tuck further infield, increasing the space outside out of their defensive block, and therefore requiring those wide forwards to cover greater distances to support the full-backs behind them.

When three central defenders are selected Roma defend with a back five, a narrow midfield three, and a front two that, like their midfielders, work to block access to the central lanes (above). Their wing-backs advance to press the ball; if their front two can learn to more effectively force play to one side of the pitch they will offer greater defensive security. Their central midfielders regularly succeed in preventing possession being played back infield, but when they do so, there are times their front two allow opponents to switch play in defence and instead tempt Roma across the pitch.

The absence of a double pivot places an increased emphasis on their wider central defenders to press into midfield. Should opponents progress centrally, or one of Roma's midfielders be tempted forwards, those same wider central defenders are particularly assertive in advancing and pressing; there, similarly, are times one temporarily helps to form a double pivot in front of a back four.

That they offer a presence in wide territory in the defensive third also means Roma's attacking central midfielders pressing into the wide areas, in turn leading to their wider central defenders contributing in midfield and preserving Mourinho's desired midfield three and, ultimately, compactness.

His occasional – and untypical – use of a back five means that Roma's defensive line can regularly sacrifice a player to contribute to their press in midfield, and complements the efforts of the front two to force opponents wide, where the relevant central midfielder and wing-back can combine to regain possession.