julian nagelsmann

Bayern Munich, 2021–2023

Julian Nagelsmann was only 28 years old when Hoffenheim made him the Bundesliga's youngest ever head coach. To provide further perspective, he was only 16 when in 2004 José Mourinho inspired Porto to Champions League glory, and was born in 1987, the year after Sir Alex Ferguson was appointed manager of Manchester United.

Nagelsmann has been heavily influenced by the pressing philosophy of Ralf Rangnick, who was behind RB Leipzig recruiting him from Hoffenheim in 2019. He was also once coached by Thomas Tuchel, who was overseeing Augsburg’s second team when a then-20-year-old Nagelsmann suffered the knee injury that would end his playing career. Tuchel first asked him to start scouting opponents, and later appointed him the coach of 1860 Munich's under-17s.

"Thirty per cent of coaching is tactics, 70 per cent social competence,” Nagelsmann once said of his approach. "Every player is motivated by different things and needs to be addressed accordingly. At this level, the quality of the players at your disposal will ensure that you play well within a good tactical set-up – if the psychological condition is right."

Playing style

Nagelsmann is an innovative coach recognised for his willingness to experiment with new technologies and data as he looks to improve as a manager and for ways to improve his team. While at Hoffenheim, a giant screen was erected at the training ground and used to correct player and unit positioning without requiring long breaks in training sessions. Those training sessions are known be played at a high intensity.

He set his team up in an attacking 3-5-2 system while they had possession, and a 3-4-3 or 5-3-2 when they had to defend. His three central defenders played out from the back. Kevin Vogt, in particular, was given responsibility for playing the ball forwards and progressing possession. In central midfield, Florian Grillitsch protected the central defenders, covered for the wing-backs when they advanced, and dropped into defence when needed. Two other central midfielders created a square structure with wide forwards Mark Uth and Serge Gnabry. This shape helped the team progress play up the field.

With a better squad at Leipzig, Nagelsmann's favoured approach evolved. His team's basic structure was a 5-2-3, but they demonstrated similar principles to those witnessed in Hoffenheim's 3-5-2 (above) and 3-4-3.

More rotations in the central lanes meant they had more chance of penetrating into the space behind the opposition's defence. Until Timo Werner's departure, he provided the majority of the team's runs in behind, and he was supported by another run from his strike partner. After Werner's move to Chelsea, they changed striker regularly, and often played in a 4-2-3-1.

There was also more variety when Leipzig built possession (above) compared to Hoffenheim, as well as when they were attacking. Their wing-backs – usually Angeliño on the left and Nordi Mukiele on the right – initially provided their attacking width, but Leipzig's focus on central rotations (below) meant that the wing-backs sometimes moved infield to attack alongside their most advanced attacker. When they did so, cover was provided by a central midfielder, while the other central midfielder moved into a position from which they could rotate either into a wide position or through the inside channels.

Opponents regularly responded to the numbers attacking through the centre by defending with similar numbers, in turn leaving them vulnerable to Leipzig attacking around the outside. The team's rotations were made possible by the versatility of Marcel Sabitzer, Dani Olmo, Emil Forsberg and others; players who were comfortable in a number of positions and could happily swap positions during a game – exactly the type of attackers that Nagelsmann likes.

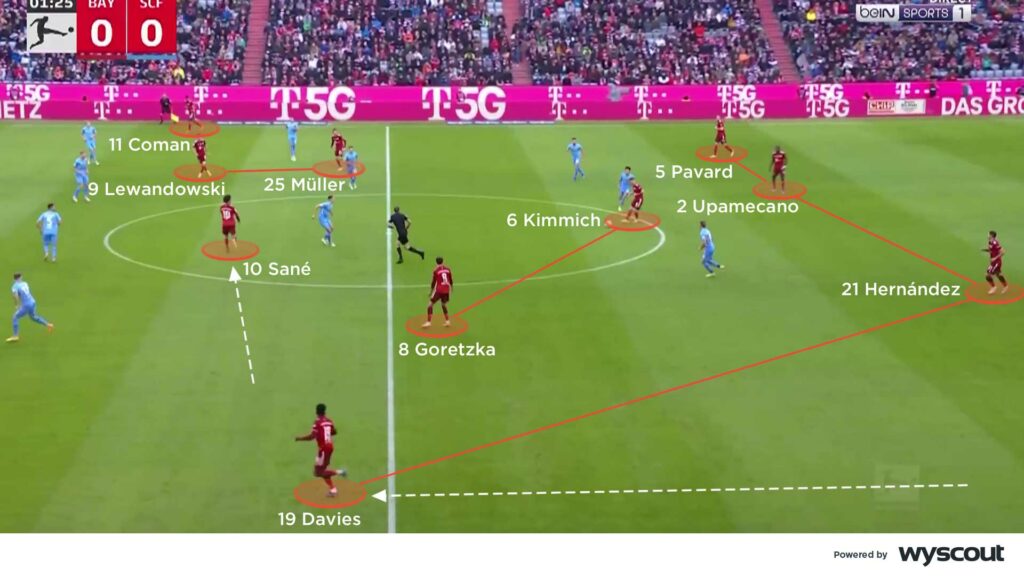

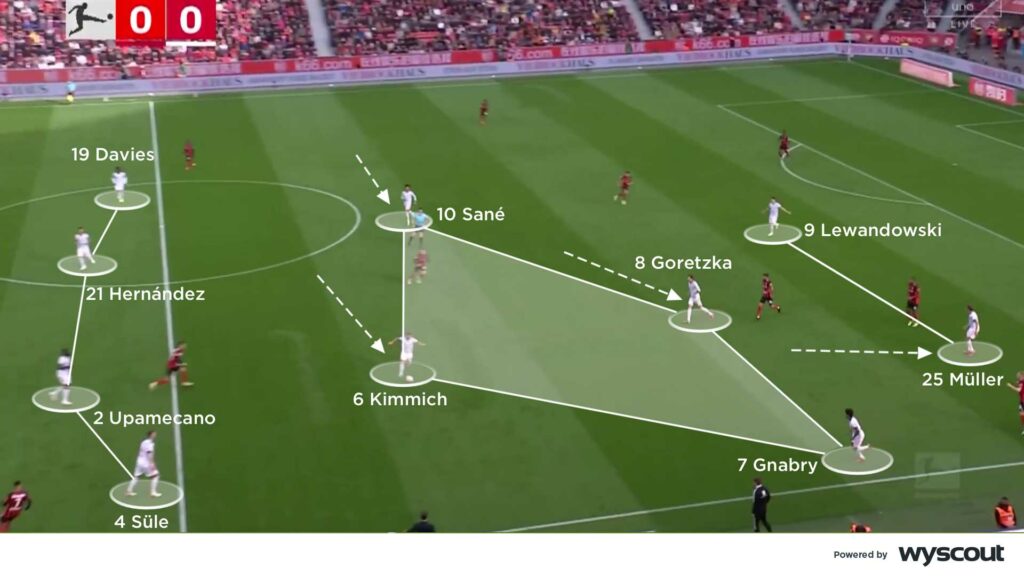

At Bayern, Nagelsmann often used a 4-2-3-1 built on the double pivot of Joshua Kimmich and Leon Goretzka. In his first season, Thomas Müller remained as the number 10 behind Robert Lewandowski, but unlike under Hansi Flick, Nagelsmann selected wide players on the same wing as their stronger foot. Leroy Sané tended to play on the left, with Gnabry or Kingsley Coman on the right. The width provided by their wide players and attack around the outside of their opposing full-backs increased the space in the middle for Lewandowski and Müller to operate in. Similarly to Nagelmann's Leipzig, Bayern's front four rotated away from the centre of the pitch, which in turn created space for Kimmich or Goretzka to advance into.

A further change involved the adventurous Alphonso Davies attacking earlier from left-back than the right-back. When he did so Sané drifted infield (below) to combine with Lewandowski and Müller and create central overloads.

After Lewandowski departed for Barcelona in the summer of 2022, Nagelsmann faced the challenge of reinventing Bayern's attack. Sadio Mané joined from Liverpool, but no direct replacement for Lewandowski was signed. Nagelsmann largely stuck with a 4-2-3-1, but with Eric Choupo-Moting playing up front and Jamal Musiala in behind him. Crossing was already less of a feature of Bayern's play under Nagelsmann, but they were used even less once Lewandowski departed. The aim was to create chances through the middle of the pitch rather than out wide.

Defending and pressing

Nagelsmann's Leipzig side were successful in pressing with a lone striker supported by two attacking central midfielders, with the three of them aiming to force play into traps out wide. If they couldn't manage that, one of Leipzig's deeper-positioned midfielders advanced to create a diamond structure with the forward and two attacking midfielders (below) that was not only difficult to play through, but could overload an opposition midfield three. After allowing an initial pass out from a goal-kick, the defence pushed up as high as possible so that the diamond had support underneath it.

If the opposition instead built out wide, the diamond of four players drifted across, and the far-side wing-back moved infield to form a double pivot with the spare defensive midfielder behind the diamond. Attacks that went up the touchline were defended against by the wing-back, the closest attacking midfielder, and potentially the nearest central defender.

Nagelsmann encouraged a high press throughout 2020/21, and he was rewarded with an increase in the number of regains in the attacking half and attacking third for Leipzig. A further consequence was that opponents were often forced to attempt long balls over their press, leading to regains in their own half, or battles for second balls in midfield.

On the occasions they didn't succeed in regaining possession in advanced areas, their priority became preventing opponents from carrying the ball through the centre of the pitch.

At Bayern, Nagelsmann's 4-2-3-1 became a 4-4-2 or 4-4-2 diamond when out of possession, with Müller or Musiala likeliest to instigate their high press by advancing to create a front two (below). When working as a two, the forwards forced the ball wide and screened passes into the opposition's defensive midfielders while moving towards the central defenders. When they required support, Goretzka moved forward to back up the press.

Both wide forwards were instructed to work back to join Goretzka and Kimmich, forming a flat midfield line when a mid-block is required, or a diamond shape when attempting to press. Whichever approach Bayern took, the wide midfielders focused on covering the inside channel before jumping out to press, allowing Goretzka and Kimmich to support the pressing efforts of their front two. On the occasions Goretzka advances, the far-side wide forward moves considerably further infield to increase their numbers in the centre of the pitch.

Nagelsmann then instructed Bayern's full-backs to push up and press, with the remaining three defenders drifting across and the far-side wide forward moving infield. Should either Kimmich or Goretzka drop back behind the pressing full-back, the far-side wide forward was needed even more in a central position. Under Nagelsmann, Bayern had many different routes by which to win the ball back, and they attacked directly towards goal quickly following a regain, with lots of players already in central positions. His Bayern side were a real force when the opposition were caught out of shape.

To learn more about football tactics and gain insights from coaches at the top of the game, visit CV Academy.