Marco rose

Borussia Dortmund, 2021–2022

It was a disciple of Jürgen Klopp who was chosen to lead Borussia Dortmund into 2021/22. Marco Rose favours the intense pressing approach with which Klopp has based his own successes as a manager. After building his reputation as the promising coach of Red Bull Salzburg, Rose more recently succeeded in leading Borussia Mönchengladbach into the knockout stages of the Champions League.

In Thomas Tuchel, who succeeded Klopp at Dortmund, Julian Nagelsmann and Rose, German football has provided three of the coaches expected to largely shape European football in the coming years. Rose, aged 44 when his latest career move was confirmed in February 2021, also featured under Klopp at Mainz during his 15-year playing career. "He shaped all of us," he has said of his former boss. "We picked up a few things in terms of football, but above all it was the way he was with people [that was influential]. Maybe there are a few parallels with Jürgen."

Playing style

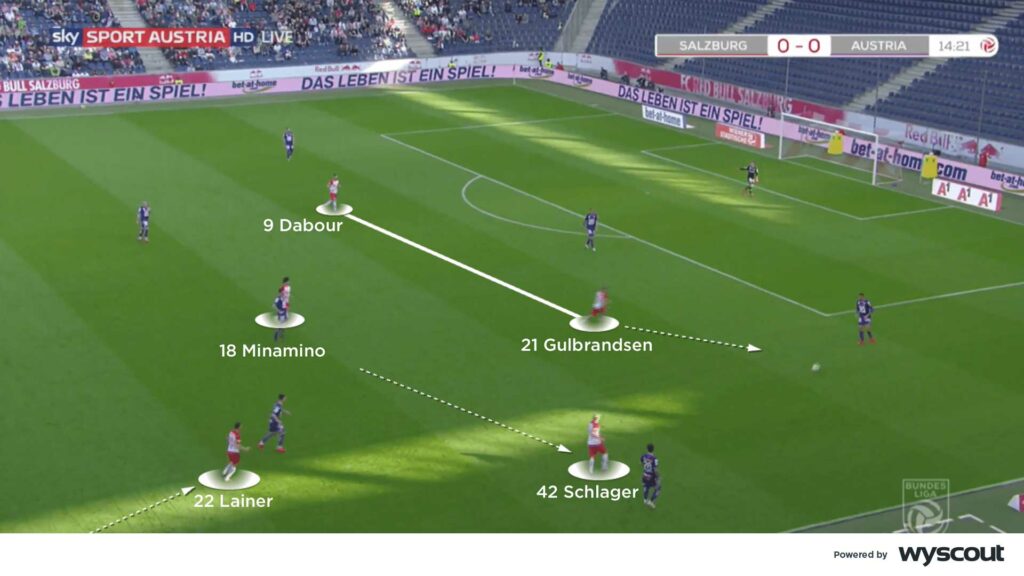

At Salzburg Rose mostly favoured a four-diamond-two formation (below), but there were periods when a flatter 4-4-2 was also used. Even on the rare occasions he wanted a back three, he continued to select two strikers. Their diamond midfield was particularly flexible – Xaver Schlager, Takumi Minamino, Amadou Haidara and Hannes Wolf all often occupied different roles – contributing to Rose's ability to make subtle adjustments to his midfield's approach.

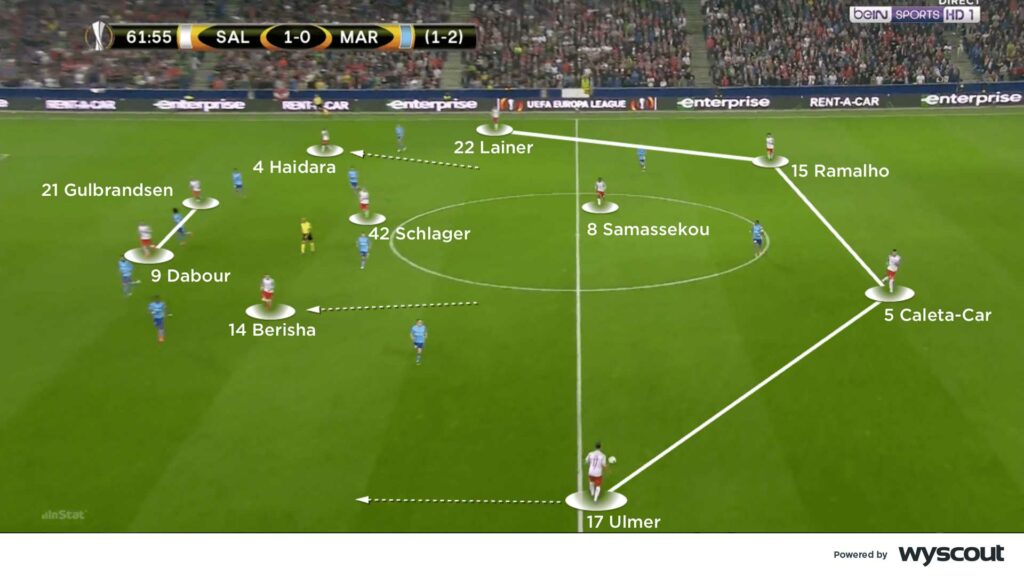

During both seasons under his management, Salzburg averaged the most passes per match in the Austrian Bundesliga, and played attacking football that meant them regularly attempting to break lines with vertical, penetrative passes. It was those who played in defence or at the base of midfield who provided the highest number of passes, often from alongside or in front of their expanding back four. Andreas Ulmer and Stefan Lainer provided the width outside of their diamond, from full-back, and then attempted to play cut-backs into the many teammates occupying the central areas of the pitch.

After progressing through midfield, Salzburg ruthlessly broke forwards – to the extent that during both 2017/18 and 2018/19 they also registered the competition's highest number of attacks into the penalty area. Both of their number eights adopted high positions through the relevant inside channel, in turn occupying their opponents' full-backs at the same time their front two had pinned back their opposing central defenders – increasing the space in which their number 10 could receive between the lines. Via him doing so, and the variety of runs offered by their numbers eights and second striker and their ability to combine, goalscoring chances were regularly created.

If opponents instead concentrated on restricting access into Salzburg's 10, their deepest-lying midfielder would instead have increased space with which to dictate their attempts to build play, and to the extent that, if necessary, their central defenders had the freedom to join him there. Their sense of balance was superb; they were as capable of building patiently as they were of executing quick combinations between the lines and into those making runs in behind – often in the same game.

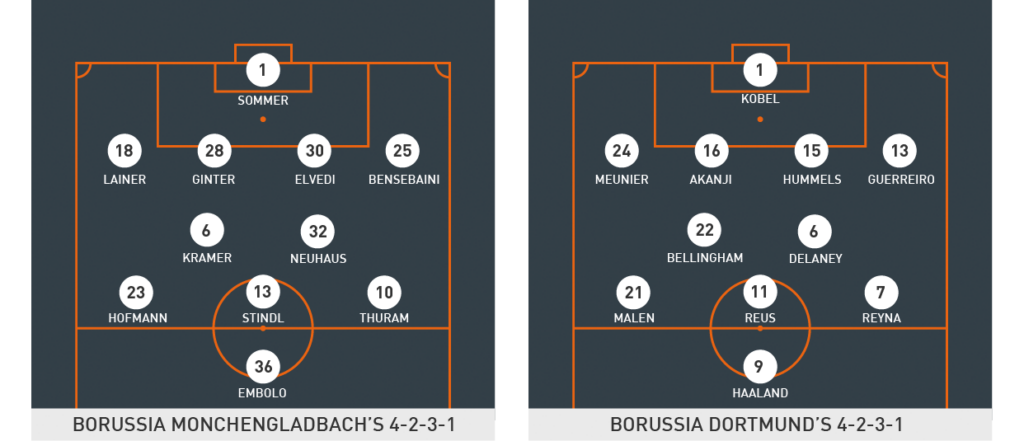

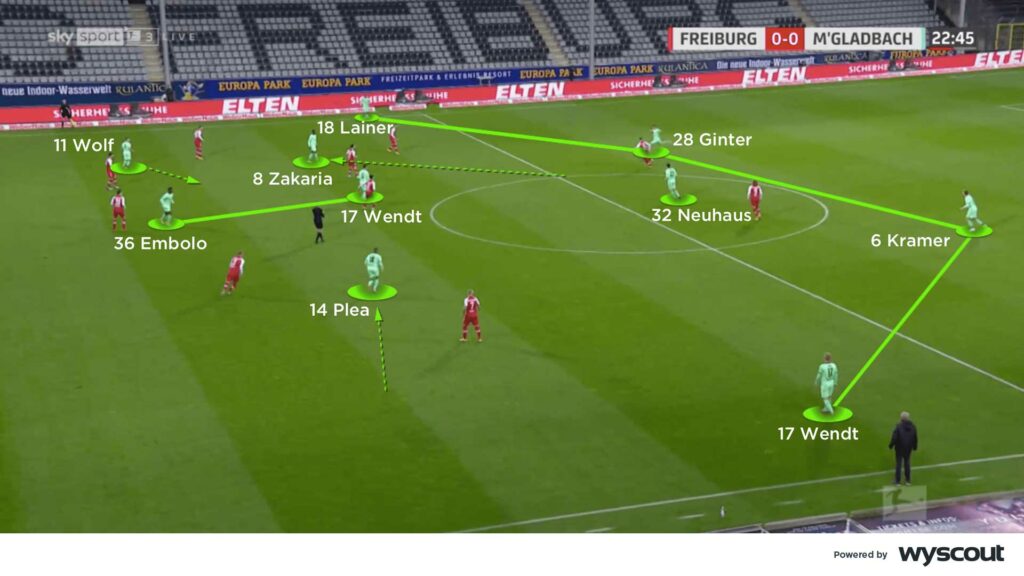

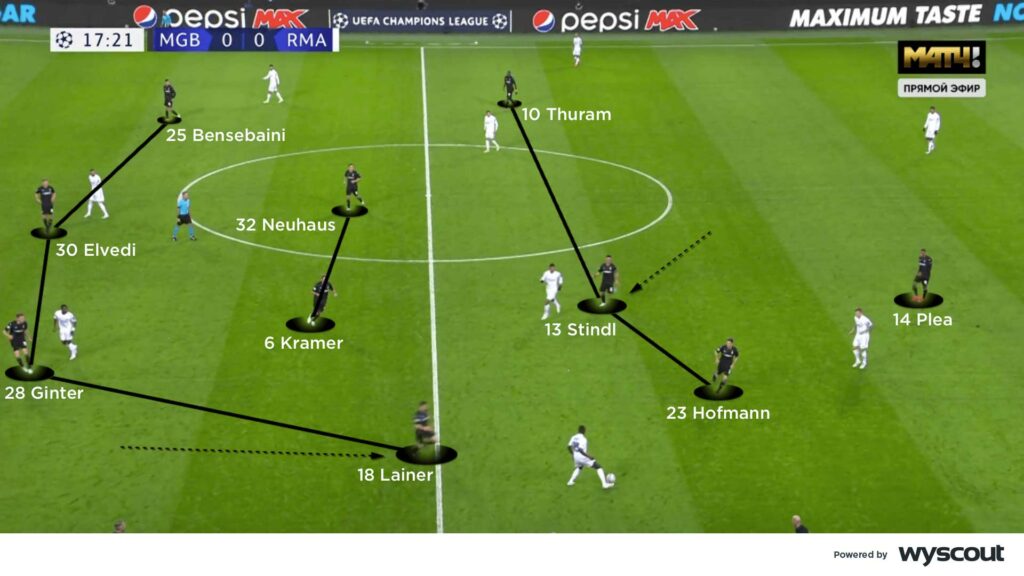

A similar four-diamond-two was initially used with Mönchengladbach, but even if their style of play mostly remained consistent towards the end of his time there, Rose's preferred shape later became a 4-2-3-1. Those in central defence and in their double pivot in midfield play the majority of their passes, their wide attackers advance through the inside channels, and their full-backs provide their width. Marcus Thuram, Jonas Hofmann, and Patrick Herrmann, as their wide forwards, largely mirrored Salzburg's number eights, and Mönchengladbach's nine and 10 – Breel Embolo or Alassane Pléa from in front of Lars Stindl – operated similarly to Salzburg's front two. Though their double pivot reduced their numbers in the final third, they built with increased security.

A further contrast involved their wide forwards attacking infield or around their opposing full-back – Salzburg's eights started and remained in narrow positions – and, as a unit, Mönchengladbach offering more creativity from deeper positions because of their somewhat reduced grasp of attacking territory and possession.

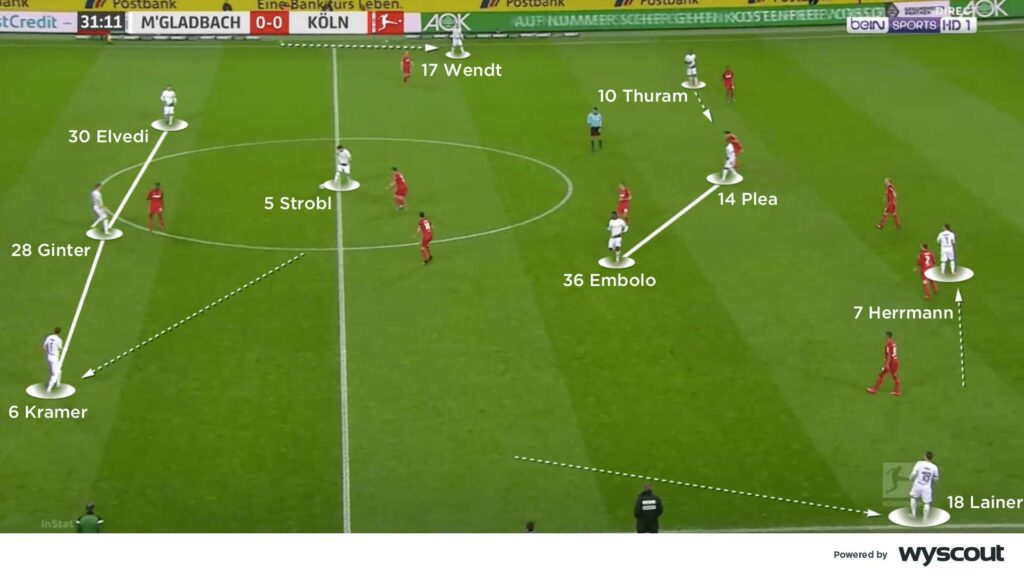

Their many similarities were led by the same desire to play vertical passes and to break lines. That they recorded more offsides than any other Bundesliga team during 2019/20 demonstrated the extent to which they, too, offered forward runs. Behind those forward runs, the additional defensive midfielder meant one of Christoph Kramer, Florian Neuhaus or Denis Zakaria offering the flexibility to withdraw from the base of midfield into central defence (above) to encourage their full-backs to advance further forwards, and in turn their wide forwards moving further infield and creating another attacking four.

Those same defensive midfielders were also capable of moving wide to support and combine with the relevant full-back and wide forward, and to offer an additional forward runner through the inside channels – one that mirrored Salzburg's eights – to also draw an opponent's press, creating increased space between the lines and ahead of the ball. Even when one of them moved, the other remained in position to provide the link between defence and midfield (below). For all of the variations that existed, the same ideas underpinned both teams.

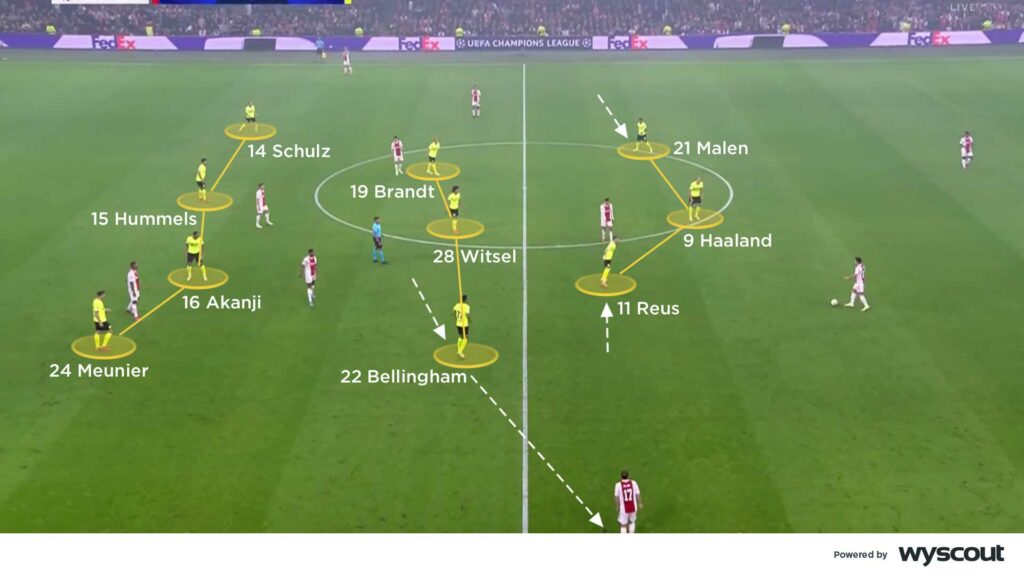

Dortmund have so far mostly used a four-diamond-two, 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1. In each system their attacking width has mostly been provided by their full-backs, and one defensive midfielder has consistently remained at the base of midfield to protect those behind him. From either their four-diamond-two or 4-3-3, their deepest positioned midfielder holds his position; from their 4-2-3-1, similarly to at Mönchengladbach, one of their double pivot advances to alongside the three in front of him and inside of their attacking full-backs; Emre Can or Axel Witsel are typically given defensive responsibility, and Jude Bellingham or Mahmoud Dahoud encouraged to attack. It is when their full-backs advance that, as with Salzburg and Mönchengladbach, there are increased rotations and movements in central territory (below); from their 4-2-3-1 those movements are complemented by their number 10 moving to alongside Erling Haaland to form a front two that occupies both opposing central defenders.

Further rotations involve their number 10 withdrawing from between the lines to instead encourage a wide player to move infield and closer to Haaland – an approach that can prove particularly effective when a second striker, perhaps Donyell Malen, is selected as a wide forward, and that creates space for their attacking midfielders to attack into. More creative wide players – perhaps Marco Reus or Julian Brandt – often move into withdrawn attacking roles in both Dortmund's 4-3-3 and 4-2-3-1, and are complemented by attacking central midfielders moving to support from behind or alongside their central attacker. Rose's new team have also proven capable of countering and transitioning into attacks at speed – particularly when direct passes are played into the imposing Haaland.

Defending and pressing

Salzburg were – alongside LASK – also in the top two for the number of regains made in the attacking half across the 2017/18 and 2018/19 Austrian Bundesliga seasons. Their intense, high press – typical of a team in the Red Bull network – was perfected via their four-diamond-two in which their number 10 screened or marked his opposing defensive midfielder and the front two ahead of him pressed their opposing defenders (below) free of the responsibility of blocking the central lane. Those leading their press may have had an increased workload, but regains were regularly achieved, and were often complemented by their number 10 advancing to alongside them to apply their press as a three.

Behind them, Rose's number eights both protected the inside channels and defended against direct balls over the first line of their press. The positions they adopted wide of their opposing central midfielders encouraged them to also press wide, often to complement their attacking teammates' success in pressing play into those areas. Those number eights were supported by their full-backs advancing; as they did, their defensive midfielder therefore withdrew into defence.

Beyond their organised higher press, there also existed an effective counter-press that contributed to the regains they consistently made. The numbers they retained in central areas led to them reacting with speed when possession was conceded; their midfield diamond and two strikers moved to towards the ball and pressured the ball carrier. Even if the ball wasn't recovered, counters were often prevented for long enough for their full-backs to recover their defensive positions.

Similar pressing principles were used by Mönchengladbach, but their 4-2-3-1 (below) meant that the first line of their press had one fewer player who instead featured in front of their defence. There were occasions when their number 10 advanced to form a front two, and when their wide forwards covered the inside channels, but unless one of their defensive midfielders moved to press his opposing number they offered a reduced presence in the attacking half.

A further approach involved their 10 remaining withdrawn and their press being applied from what continued to resemble their starting shape, to encourage the ball in one direction and force it to one side of the pitch; their striker restricted access between the opposing central defenders, and the 10 behind him prioritised the defensive midfielder. There also existed an increased focus on individuals that involved marking more tightly over covering passing lanes and spaces.

Mönchengladbach's full-backs, as with Salzburg's, advanced to support a wider press behind the wide forwards covering the inside channels, and they used the touchline to do so. Their overall counter-press also led to them making an increased number of interceptions during Rose's time as their manager; their front four offered similar potential to that he oversaw at Salzburg, and when their double pivot was preserved they retained sufficient cover to also delay counters and guard against transitions.

Dortmund typically have an increased grasp of possession, and complement their time on the ball with both a mid-block and a high press intended to contain opponents in their defensive half. They also mostly favour an out-of-possession 4-2-3-1 in which their striker attempts to screen forward progress from between their opposing central defenders, their 10 withdraws to support in midfield, their wide midfielders tuck infield to alongiside their double pivot, and their full-backs apply an aggressive press. If they are instead defending with a 4-3-3, their narrower attacking line (above) works to cover central territory and, through the closer support provided around Haaland, poses an increased counter-attacking threat.

When defending from a mid-block, their wide forwards provide effective cover of the inside channels, encouraging their central midfielders to adopt wider positions from where they can press and trap the ball towards the touchline. It is when the inside channels aren't appropriately covered by their attacking line that Dortmund's midfield three are forced to adopt a narrower shape that potentially gives their opponents easier access to the final third and to those between the lines – not least if their wide players had already committed to pressing forwards. The different characteristics offered by their attacking players presents the potential for Dortmund to defend with a 4-4-2, via one wide forward retreating into a flatter midfield and the other moving to form a front two, or even with a four-diamond-two intended to crowd the centre of the pitch.