Mark Warburton

Queens Park Rangers, 2019–2022

4.42am. Every single working day.

That’s what time my alarm would go off.

This was long before I was a manager. I spent 20 years as a trader in the City first.

4.42. It sounds so boring, but that time is imprinted on my brain. I’d be out of the door by 4.55 and on the 5.12 train to Liverpool Street. By ten to six I’d be at my desk, first coffee of the day in hand.

I’d work flat-out all day and wouldn’t get home until 7.30pm. Then there were calls from New York, Hong Kong, Tokyo long into the night.

Then 4.42 came around again. And up you get.

The difference from my job now was that I had the weekends to recharge, to spend some time with my family.

I also had some time to broaden my horizons, and to get experience of coaching.

I started getting in even earlier so I could leave early and attend training sessions at Watford to expand my knowledge. That meant getting a cab in, because it was so early that the trains hadn’t started for the day.

But I was still getting home at 10pm after being at Watford. And my alarm would still go off at 4.42. Again.

It was a super-competitive environment at the bank. It was male-dominated back then. Lots of guys wanting to do well and making a lot of money.

"That was the moment when I knew I it was time for me to make a change"

I was working in the foreign exchange currency-trading markets. Our desk of 10 guys would turn over 20 to 25 billion dollars a day. That was a normal day. On other days, we’d do more.

So, there really was significant responsibility on the shoulders of these young guys.

I loved that responsibility and pressure, but it started to become too much work for me with my coaching on the side.

One day, after I’d got in early, I was desperate to leave at 4.30pm to get to Baker Street and get on a train to Watford.

A huge deal came in. The kind of trade that people celebrate; the kind that only happens a few times a year. A really big earner.

But I was concentrating on the piece of paper in front of me. I was designing a passing drill for the Under-13s at Watford.

That was the moment when I knew I it was time for me to make a change. I knew, from that moment, that what I was doing wasn’t for me.

It wasn’t an easy transition at all, though. I don’t want to paint this rosy picture of jumping from one career to another. It wasn’t just ‘do your badges and everything is good’. Far from it.

It was a very, very tough ride, and I had to make lots of sacrifices. My family gave me a lot of support, and I was very fortunate to get the opportunities I did at the Watford Academy.

"While I was working my way up at Watford, I was forging an idea of the coach I wanted to be"

But I knew I couldn’t go straight from the City to a full-time coaching role without improving my education. I wanted to see how the best kids in Europe were trained: what the coaches did; how they dealt with growth spurts; when they moved kids up an age group; nutrition; when the psychologist came in. There was so much to learn.

I was used to cold-calling banks to get business. And here I was, using those skills to cold-call clubs.

I was getting rejection after rejection, when I eventually got through to a guy called Diogo Matos at Sporting Lisbon.

“If you can play golf, and you can get on a plane, you can be my golf partner tomorrow morning,” he said.

I got on the next flight to Lisbon, and spent a few days talking to Diogo whenever he could spare me the time.

I will forever be grateful for the access he gave me to such a brilliant institution. He also gave me contacts at Ajax, Barcelona and Borussia Dortmund.

I count Diogo as a very dear friend now. I have friends, too, at those clubs I worked with long after those first meetings. Each of those clubs played in the NextGen Series, which I later set up for Europe’s best youth teams to compete against one another.

I knew how coaches could shape young players from my own experience as a player. I hadn’t played to a high level at all – I was a bang-average non-league player – but I did play youth football at Leicester. While I was there, I was coached by Jock Wallace.

"The City demanded more of you than any other industry, so I was used to working hard. I took that into football"

He was old-school. It was a different time. He was hugely successful – a legend up at Ibrox. But his way of doing things just wasn’t for me. He was a former marine and ran his players into the ground.

That allowed me to work out very early on that that wouldn’t be how I’d do things.

I knew I would want to create a positive environment, like we did in the dealing room at the bank. People respond to that kind of thing. I wanted my players to enjoy my coaching.

So, while I was working my way up at Watford, I was building my knowledge and forging an idea of the kind of coach I wanted to be. I was taking bits from all of the different coaches I’d met all over Europe.

I don’t want to sound too old-fashioned, but it was all underpinned by hard work. The City demanded more of you than any other industry, so I was used to working hard. I took that into football.

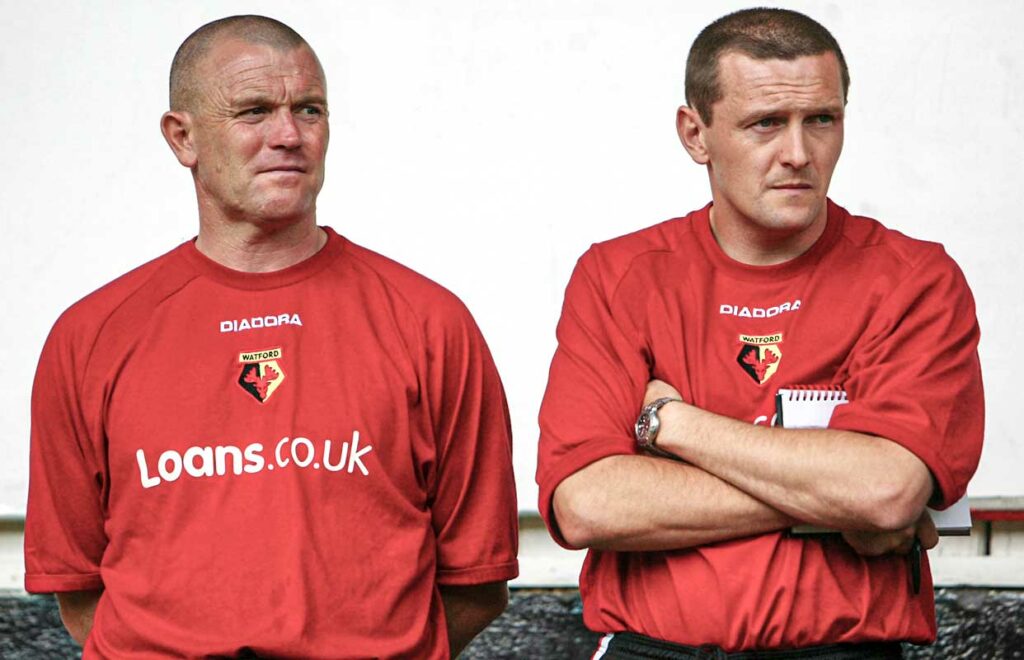

I’d make sure to be first in every morning. That allowed me to meet Aidy Boothroyd (above). We’d have a coffee together, and often go for a run first thing. All of a sudden, you are talking to the first-team manager regularly.

He asked me to present to the players and staff about working in the City. He was intrigued about that side of things.

It gave me a hook with the players. I hadn’t been a professional player, so I needed something like that to gain the respect of the players. Otherwise, that could have been my Achilles heel.

I knew I had to be aware of my weaknesses.

"I was angry and frustrated, but in hindsight it was the perfect job for me"

It all spiralled for me at Watford. I went from the Under-13s up the age groups, and eventually became academy director. Then, after I’d left Watford, another opportunity quickly came along.

I’d got to know Matthew Benham a few years earlier. We had collaborated on the NextGen Series, and he’d since bought Brentford.

One night in February 2011, I got a call at 1am. Matthew had just sacked the manager, and he was asking me to come in and help Nicky Forster – the caretaker player-manager – with coaching the first team.

I got straight on to Google and spent the rest of the night looking up the players in the Brentford squad, trying to learn their names. I knew nothing about them!

It was my first exposure to first-team football, but I made sure to apply the same principles as I did to youth football. The players had to enjoy themselves.

From day one, they were receptive to me and Nicky. The team was 19th in League One when we came in, and we finished 11th.

Nicky was the face of it, but he hadn’t taken a single session. He was still playing. I had four months of first-team coaching, so that built my confidence massively.

At the end of the season, there was no doubt I wanted that job full-time. It wasn’t clear who would be in charge for the following campaign. I put my name in the hat.

But Matthew told me he wanted me to become sporting director. Uwe Rösler would be the manager.

I was angry and frustrated. I couldn’t believe it.

"we were brave on the ball, and teams underestimated us – we did more than just survive"

But, in hindsight, it was the perfect job for me.

I was able to see how a football club worked: the different structures and departments, and how they all interacted with each other. I also dealt with agents, from which I learned a lot.

It was a brilliant all-round education that really set me up for the rest of my career.

I built good relationships with the players we signed. The likes of Adam Forshaw, Stuart Dallas and Jake Bidwell.

That meant that, when Uwe left for Wigan in December 2013, the players knew me. Matthew offered me the job this time, and we hit the ground running.

I was very aware of my biggest weakness, though: my lack of playing career. So, I brought in David Weir (above) – a legend at Rangers and Everton – as my assistant. I needed someone who filled that gap for me.

We made a great team. The club was fourth when we took over, but we lost only four of our remaining 27 games and went up in the automatic promotion spots. We ended a 21-year wait for Brentford to get back into the second tier.

As we prepared for life in the Championship, I received the same piece of advice from lots of people.

“Just survive,” they said. “Do what you need to survive in that league.”

So, we put in a really aggressive bonus scheme. We used the loan market well, and we went for it.

"The players rallied around me. They were magnificent"

We were brave on the ball, and teams underestimated us. In the end, we did more than just survive.

We had a really tight-knit group. Everyone was very close. We used the joint fewest players in the Football League that season: just 24 players in an entire 46-game campaign.

We’d done some brilliant business in my time there. We had Andre Gray, James Tarkowski, Adam Forshaw, Stuart Dallas, Jota. Players who were on their way to the top.

Matthew wanted to start using analytics to make signings, and he wanted to do it in the January transfer window. I didn’t doubt the quality of the players he wanted, but I was worried about how lots of mid-season signings would affect the feeling in the group.

He was the owner, and he was totally within his right to take the club in the direction he wanted. But I didn’t agree with how he thought it should be done.

One Sunday in February, I was having a coffee with David Weir, and we saw an article headlined: “Rayo Vallecano coach turns down Brentford job.” It was the first either of us had heard of it.

I went in for a chat with Matthew, and he was very honest with me. He told me the complete truth and I thanked him for that. He asked me to stay on for the time being, but just until the end of the season.

The players rallied around me. They were magnificent. After an Andre Gray goal away to Watford in early February, they all ran and jumped on me (above). I didn’t know they were going to do that, so it was a special feeling. More importantly, it showed the unity in the squad. It was a tight group, and we stuck together.

We ended up finishing fifth in Brentford’s first season back in the second tier, which was an incredible achievement.

We played Middlesbrough in the playoffs, but it wasn’t to be. I think the realisation of the situation – how close they were to the Premier League – really struck the players.

"When I walked in the door at Rangers, I could instantly tell I was somewhere special"

We had a lot of young guys in our squad, who had played with a freedom and a fearlessness throughout the season. They weren’t scared of anything.

But suddenly, here we were, three games from the Premier League, and you could almost sense a tangible lack of belief from the players. It wasn’t the normal Brentford side I knew.

That was when I knew we weren’t going to do it, but the players deserve so much credit for the way they approached that season. On one of the smallest budgets in the league, we came so close to promotion.

My work, meanwhile, got noticed elsewhere. After I left Brentford, I was fortunate to get some fantastic offers. I had big clubs in England approach me, but my son had other ideas when I got an offer from slightly further afield.

Rangers came in with an offer. David Weir insisted I had to speak to them but, to be honest, I was giving a lot of consideration to the offers from England.

Then my son showed me an eight-minute YouTube video of the build-up to an Old Firm game at Ibrox. I knew after watching it that I couldn’t turn Rangers down.

It was such a privilege to even be offered the position. When I walked in the doors, I could instantly tell I was somewhere special.

I quickly saw what football meant to the people up there. You’d get 50,000 people at home games – even in the Scottish Championship, as we were then – and a fantastic away following.

It’s important for a manager to understand a club you’re walking into. I mean more than just the playing style the club wants, but also what it means to the fans, and the relationship the club has with them.

"To be on the touchline at Parkhead and Ibrox in Old Firm derbies was such a privilege"

These fans had watched Paul Gascoigne, Brian Laudrup, Ally McCoist. New fans weren’t put off by the club’s time in the lower leagues. It was in their blood.

You realise very quickly how big an institution you’re at, and how much responsibility you have to half of Glasgow.

If you went in at half-time drawing 0-0, the fans will boo. “They expect you to beat Barcelona,” David once told me.

But then you come out after the break and the noise is incredible. Straight away, they’re right behind you again.

I found it frustrating that people said you could never understand what it meant to manage Rangers as an outsider. I absolutely knew what it meant. It was impossible not to feel the passion.

We had a fantastic time there. We won a league-and-cup double in my first season, and got promoted at the first attempt. There was also a win over Celtic, who were untouchable at the time, in a Scottish Cup semi final, despite us being in the division below.

To be on the touchline at Parkhead and Ibrox in Old Firm derbies was such a big privilege.

My frustration about my time at Rangers was that, in my second season, when Celtic had their best ever season, I lost my job with Rangers second in the table. Celtic set a European record of 106 points under Brendan Rodgers. They went the entire season unbeaten.

"We were playing well, but we kept missing out by the finest of margins. I honestly believe I was one game from being sacked"

But the gap at the top was 20 points, and the owners decided that was too much. It really was a bitter pill to swallow, but I had to move on.

After a short stint at Nottingham Forest, I got back in to work at QPR in May 2019.

I was told early on that the budgets were being cut. We lost 13 players in my first week in the job. Five of them were first-team players who were just too expensive to keep on – including Jake Bidwell, who I’d had at Brentford and would have loved to have kept.

We had a complete rebuild. Just like in the City, and just like at Brentford, I set about creating an environment that the players enjoyed.

Over my first two seasons, there was massive overhaul in the squad. There wasn’t enough continuity and we struggled for consistency.

Midway through my second season, we found ourselves in the bottom half of the table, not all that far above the relegation zone. We were playing well, but we kept missing out by the finest of margins. I honestly believe I was one game from being sacked.

We played bottom-of-the-table Wycombe, and won 1-0. Without that result, I think the trigger might have been pulled. I would have understood the decision.

"I feel proud to have got to where I am without having had a playing career"

But I knew we were playing good football, and things clicked shortly after. We had a magnificent second half of the season, won nine of our last 14 games and only finished three places outside the playoff positions. You could sense we were building something really good.

We took that momentum into 2021/22, too. We had a winning mindset now. I was fortunate to be given that most valuable of commodities: time. And we were rewarded.

Only Manchester City, in the top four divisions, ended up winning more points than us in 2021.

I just want this squad to be able to realise its potential. Given the progress we made in seasons one and two, we have to be aiming for improvement once again, and that means the playoffs. No football fan in their right mind is happy to be standing still.

I want to manage in the Premier League. I’m ambitious. My career – both in trading and in football – has shown that.

You gain confidence from building a CV in any industry. Just like in the City, where you build confidence from working at bigger banks, in football you build confidence with the success you have in big jobs.

I feel proud to have got to where I am without having had a playing career. It would be a massive achievement if I could manage in the Premier League.

Given there was once a time when I was sat in a bank wondering if I could ever get a job in an academy, I’ve come a very long way.

Mark Warburton