mikel arteta

Arsenal, 2019–

Profile

Arsenal turned to their former captain Mikel Arteta when they needed a new manager to revive their season in December 2019. Following the departure of Unai Emery, Arteta was handed the reins at one of the world's leading clubs in his first managerial position, and a new project began.

Arteta was backed to shape the squad as he saw fit, and he quickly set about moving on some of the older players who had served Arsène Wenger, the club’s most successful manager, well towards the end of his 22-year tenure. The new manager’s work brought about almost instant reward, when Arsenal won the 2019/20 FA Cup, beating Manchester City in the semi final and Chelsea in the final. It nevertheless still took a while before his imprint on the team’s style became clear.

Arteta may still be learning his trade as a head coach, but he is able to draw on plenty of experience with two of the best managers of the modern era. Having spent five years playing Wenger at Arsenal, Arteta than enjoyed three years as a coach under Pep Guardiola at City.

“I had a lot of joy working [with Guardiola] and success,” Arteta said. “We spent a lot of time together and he is a friend. I have to apply my own things. He was part of my development as a person to go through a lot of things I experienced next to him. It was a privilege and of course a lot of the things I took on board, that I felt from my time at Barcelona, we shared together and a lot of things I learned from his management. I always talk with him. He is a really good friend of mine.”

Playing style

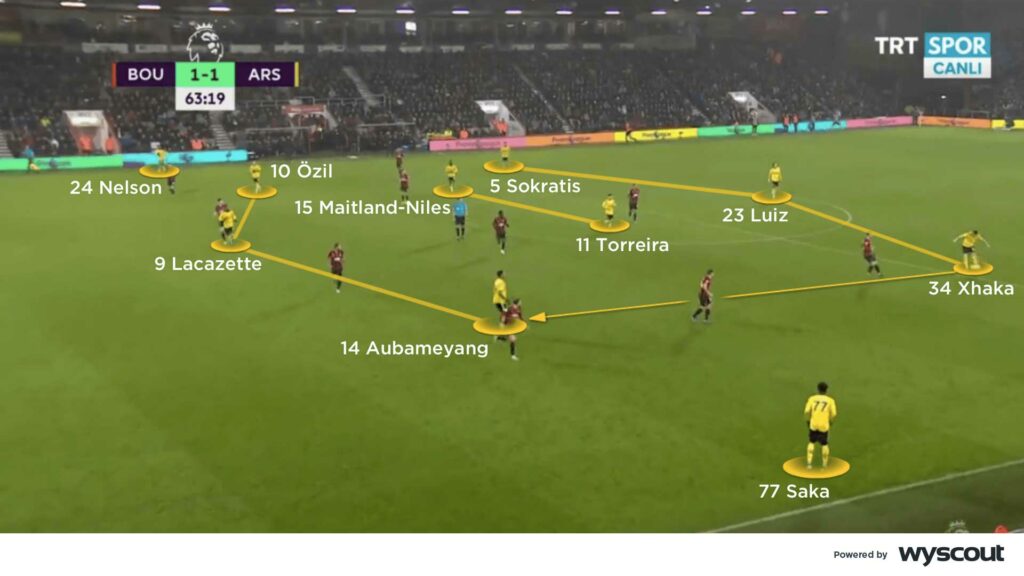

Arteta has experimented with several different systems during his short time in management. The first was a 4-2-3-1 which converted to a back three through Granit Xhaka withdrawing into central defence and Arsenal’s full-backs advancing during the early stages of their build phase (below). In front of them, the left-sided wide forward – Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang in the early days of Arteta’s reign – attacked infield and linked with the centre-forward and number 10 – usually Alexandre Lacazette and Mesut Özil. On the right, Nicolas Pépé – and later Bukayo Saka – remained wide for longer, and then looked to dribble inside on to his left foot. This ensured an asymmetrical shape that was more difficult for the opposition to deal with.

There were also occasions when the wide forwards both stayed wide and the striker moved to become a second number 10 in front of a single pivot. When the full-backs pushed up, the wide forwards then attacked towards goal into the space the centre-forward had vacated. Arteta’s early Arsenal side blended a direct approach with some longer spells of possession, and constantly looked to get their wide players into the spaces behind the opposition's defence.

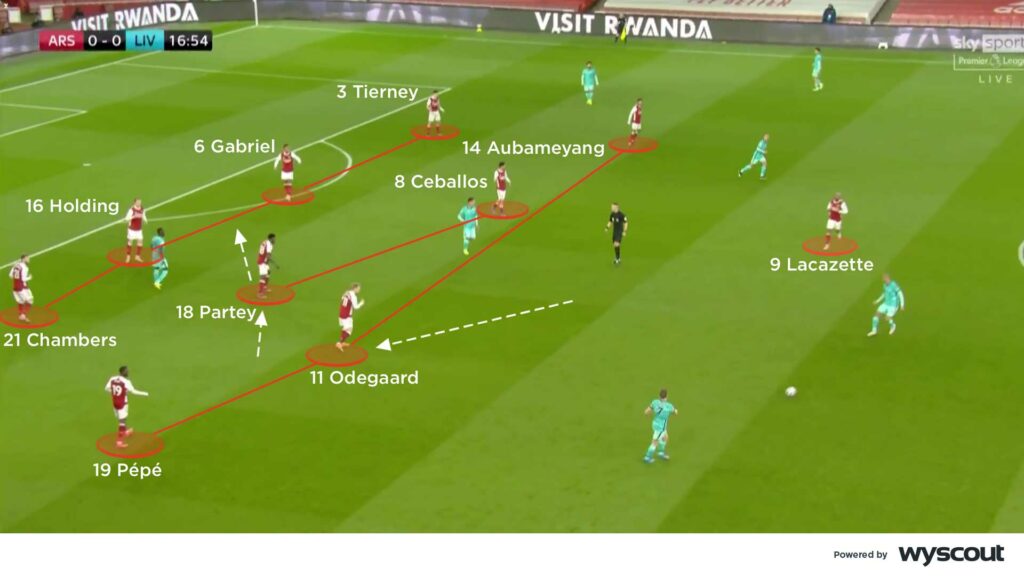

Arteta also started with a back three on occasion – usually when he wanted his team to sit back in a deeper block. Their left-sided wing-back – Kieran Tierney, Ainsley Maitland-Niles or Saka – advanced, and on the right Héctor Bellerín remained withdrawn, which meant his team could switch to a back four during a game. On the left side of attack, Aubameyang moved infield to join the centre-forward in attack, leaving a bigger gap on the flank for the wing-back to attack into. This meant Arsenal often attacked with two strikers in central positions.

Whatever the formation, Tierney was free to attack in the knowledge that Xhaka would move across from central midfield to cover for him. If Tierney was selected on the left side of a back three, the left wing-back would move infield to take up the position that Xhaka had vacated in central midfield. While making Arsenal’s players more difficult to track, these rotations also meant Arteta's team were more effective at switching play, with width on both flanks and a midfielder constantly underneath the ball.

There were also times that the 3-4-3 Arteta used was more rigid. Both wing-backs attacked at the same time, their wide forwards moved infield, and the double pivot was preserved. This coincided with Özil departing, though, and without the midfield rotations or their primary creative midfielder, they struggled to create space and to release their attacking players in the final third. Arsenal’s possession share increased in this time, but they became somewhat toothless in attack.

For the majority of his Arsenal tenure, though, Arteta has favoured a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1, with a lot of emphasis on into getting into dangerous wide positions to put crosses into the box. Before Martin Ødegaard’s arrival, in particular, this was a response to his team’s lack of creativity in central midfield. Another experiment in their 4-2-3-1 involved Lacazette playing as a number 10 behind Aubameyang. However, the Frenchman struggled to link play in more crowded areas, and Aubameyang became less effective without the opportunity to make diagonal runs off the flank into the space in behind.

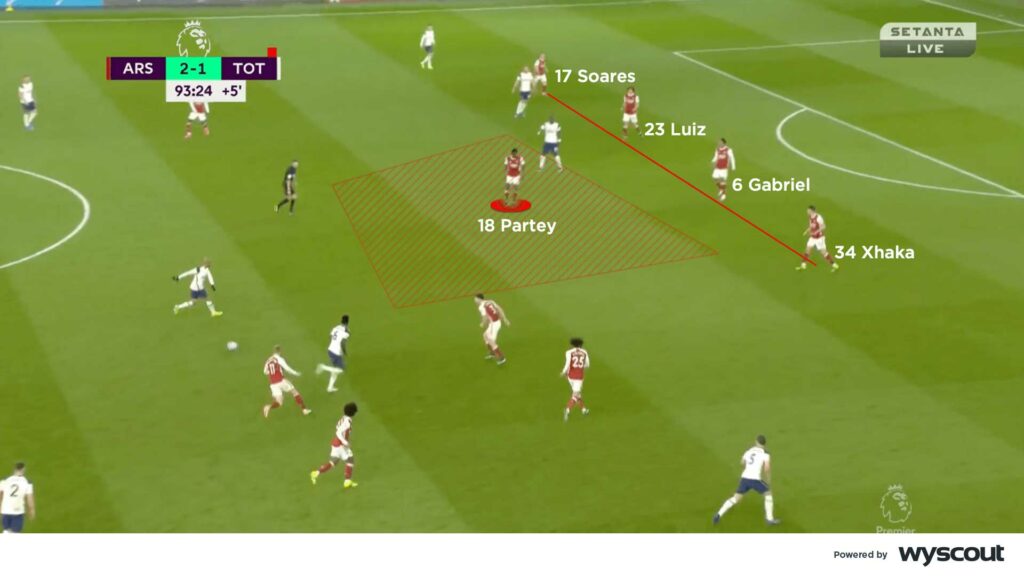

Arsenal improved over the course of 2020/21, with Thomas Partey in a double pivot alongside Xhaka. Gabriel Martinelli made a willing runner off the wing, while Emile Smith Rowe emerged in midfield and helped drive the team forwards, and Odegaard provided some calm, assured, progressive passing in central midfield.

Arsenal's build-up play became more fluid, with third-man combinations a prominent part of their play to release players out wide. This means the wide players are in a position to cross or cut the ball back under little pressure, and can therefore take the time to pick out a teammate, rather than aim a cross into an area for a big centre-forward to attack.

Tierney and Takehiro Tomiyasu then became Arteta's preferred full-backs, and their attacking runs complemented the fact that the wide forwards – the right-footed Martinelli on the left and left-footed Saka on the right – wanted to attack infield. Whenever Smith Rowe played as the number 10, he provided dribbles through the centre of the pitch, which helped free up Arsenal’s wingers by drawing opponents towards the ball. Smith Rowe proved adept at then finding the narrowed wingers in the inside channels.

However, if Ødegaard was used as the 10, the Norwegian provided better passing ability and less in the way of driving runs with the ball. He played early forward passes, while also dropping deeper than Smith Rowe to combine with the double pivot. Martinelli and Saka then had more space between the lines, and often took up number-10 positions to support the centre-forward.

Gabriel Jesus, who joined in 2022, added another element to Arsenal’s attacking play, as he is happy to drop in and rotate with Ødegaard as the 10, or drift wider and rotate with a winger. Jesus combines the link-up play of Lacazette with the clinical finishing, penalty-area presence and movements in behind of Aubameyang.

Full-backs in Ben White and Oleksandr Zinchenko like to get on the ball and come into narrow positions to try and connect directly into Jesus. This allows Saka and Martinelli to hold their width and often attack around the opposing back line. This has also allowed one of the double pivot to push forward, acting as a temporary number 8, with Ødegaard pushing up. Arteta is slowly working towards playing with the same 2-3-5 attacking shape which he helped coach at Manchester City alongside Pep Guardiola (below).

Defensive phase

Early in Arteta’s Arsenal reign, they showed impressive defensive resilience when playing with a back five (below). They were noticeably more aggressive in their defending, and the low block they played against opponents who dominated possession brought about some noteworthy success, not least in their FA Cup win in 2019/20.

A low block was used in an out-of-possession 5-4-1, 5-3-2 or 5-2-3 depending on the opponent. They used a 5-4-1 to allow the opposition to build until deep into the Arsenal half, and a 5-2-3 or 5-3-2 to maintain a greater counter-attacking threat at transitions. Both systems increased the demands on the central midfielders, which would have been a big part of the reason Arteta made it a priority to sign Partey.

Arteta would prefer his team to dominate possession, though, and that tactic was only ever going to be a temporary measure. The following season, there was a significant increase in the amount of high pressing Arsenal did, and they played far more frequently with a back four.

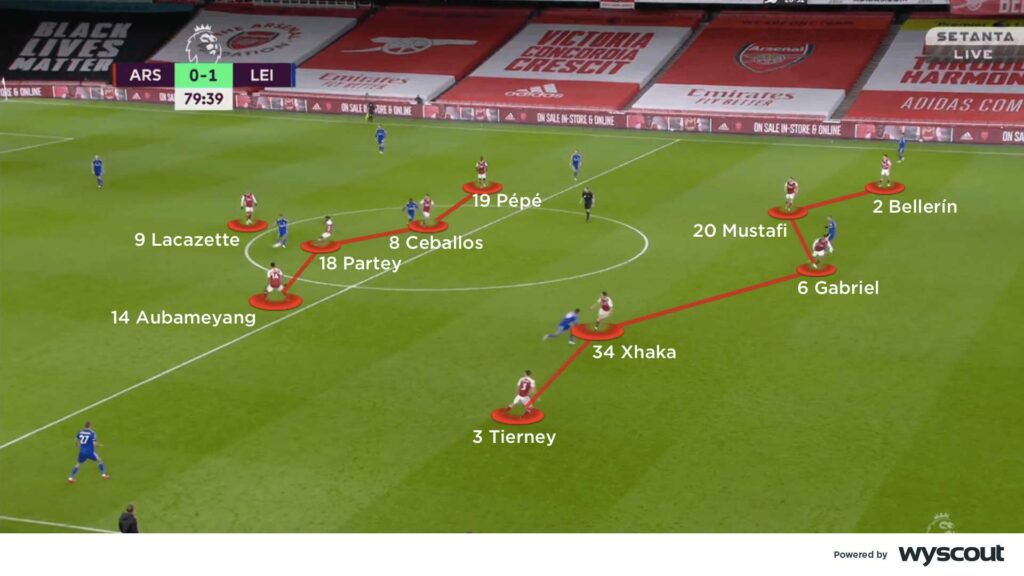

When they used mid-block and a back four, too much space began to appear between the lines and their defence was too often exposed. The forwards were needed high up the pitch to press and the full-backs pushed up to support the press. When they lost the ball, there was too often too little protection for the central defenders and they were left exposed.

Arteta was again forced to compromise, and the team’s front-foot defensive approach was sacrificed. The double pivot were asked to remain in place to protect the back four, and the number 10 and wide forwards dropped back into shape quickly when possession was lost (above). There were even occasions when one of the double pivot dropped back into the defensive line to form a temporary back five, with the 10 then replacing them in the pivot.

More recently, Arsenal have defended in a 4-4-2 defensive block in which their 10 joins the striker to ensure an increased presence in front line. This helps them force possession wide earlier and reduces the chances of the opposition penetrating through their structure. A compact shape is required, with the far-side players coming infield to keep the pitch small, in the process conceding the far side of the pitch. Arsenal have had to improve in how well they retain their defensive shape in order to play this way.

The recruitment of White, Tomiyasu and Jesus has not only given Arteta a younger team, it has also allowed him to gradually return his Arsenal side to a more aggressive pressing unit, with the 4-4-2 ready to jump high when appropriate.

Arteta’s 4-4-2 block continued to force the ball wide in 2021/22 and into 2022/23, with the winger and full-back pairing very aggressive in trying to win the ball back once the ball passes the midfield line. At that stage, Arsenal’s full-backs aggressively jump out to engage the ball carrier. The aim here is to prevent the opponent from progressing further, before the winger presses the ball carrier from the other side, and the ball-side double pivot slides across. The three of them try to lock play near the touchline before an attempt to regain possession is made (below).

It’s also common to see the centre-forward push across to help lock the ball on one side, while Saka, Martinelli and Smith Rowe provide impressive pressing intensity. They are now backed up by Jesus – one of the best pressing forwards in world football – and his ability to recover back into midfield has only helped the team further.

Under Arteta, Arsenal are still a work in progress, but they are an improving side with plenty of potential and a clear aim as to where they are going. As his young team takes on his ideas further, Arteta’s Arsenal could yet get even better from here.

To learn more about football tactics and gain insights from coaches at the top of the game, visit CV Academy.