Paul Dickov

Oldham Athletic, 2010-13

As Oldham manager, normally, my press duties just involved a chat with Latics TV and talking to a bloke from the local radio station.

But the final week of January 2013 was very, very different.

It was FA Cup fourth-round week, and Brendan Rodgers’ Liverpool were coming to Boundary Park.

At the time, Oldham were knocking around in the bottom half of League One. Liverpool had Steven Gerrard, Luis Suárez, Philippe Coutinho, Daniel Sturridge, Raheem Sterling, Jordan Henderson, Joe Allen. They were a frightening side.

There was no getting away from the media in that week. All the big outlets were coming in to find out about us, do features, speak to me. They were everywhere.

It was an exciting week, but I tried to keep training as relaxed as possible. We basically just played five-a-side all week. Not once did I mention Liverpool to the players.

I didn’t want the players to be overwhelmed by all the media. Some players can handle that pressure, but plenty can’t, so I just wanted the week to be as fun as possible.

Usually, before a game, I would run through the opposition’s players at a team meeting; talk about how we were going to play.

“I told my forwards I wanted them to batter the Liverpool centre-backs”

On this occasion, I didn’t even do that.

The only thing I did was, as the players left the training ground on Saturday ahead of the game on Sunday, to tell Robbie Simpson, Matt Smith and Jose Baxter – our main three attacking players – that they were all playing.

I often didn’t play all three. When we wanted to be a bit more conservative, I would only play two. For this game, I told them we were going to go for it.

Matt was massive, a really big striker, and Robbie and Jose were good physical specimens, too. But they were all good players as well – better than they were given credit for, for sure.

They could hold their own against a good team. I told them I wanted them to batter the Liverpool centre-backs.

Robbie and Matt played up front, and I played Jose as a number 10 behind them. I told the team we were setting out to win the game. I just asked Jose to make sure he got back in when we lost the ball to make two banks of four.

Before the game, I told the players that, every year in the FA Cup, there are one or two players who make a name for themselves against a big club. Players who do something special and make a career out of it afterwards. I gave them examples, like DJ Campbell, who had impressed for Yeading in a televised cup tie against Newcastle and went on to succeed at a higher level.

“A few of them did what I said they could do. Matt Smith got a career out of that game”

That was the last thing I said to them before they went out. I told them to make sure they didn’t leave anything out there. This was their chance.

Brendan didn’t play a weak team. Gerrard didn’t start, but Suárez, Sterling, Sturridge, Henderson, Allen and Martin Skrtel all did.

But the desire my players showed was unbelievable. Just how up for the game they got is something that still makes me proud today.

And the performance was something else.

We went ahead early on through Matt Smith, but then got pegged back by Suárez.

But we dug in and produced an amazing performance to score either side of half-time and go 3-1 up. Liverpool brought Gerrard, Stewart Downing and Jonjo Shelvey off the bench. They pulled one back and there were a few scary moments, but we clung on to win.

It was an incredible achievement. To a man, my players were unbelievable. On sheer desire alone, they definitely deserved it.

A few of them, including Matt Smith (above), did what I said they could that day, and made a name for themselves. He got a career out of that game. He went on to sign for Leeds and play in the Championship for years.

“The young players knew that everyone had a chance”

My players going on to bigger things was a consistent theme of my managerial career.

Giving youngsters a chance has always been important to me, and the success I had in that regard fills me with joy.

When I came to Oldham, Dean Furman couldn’t get a game. He became a key man for me, and he went on to become captain of the South Africa national side.

I gave a young James Tarkowski his debut, too, and obviously he’s gone on to do very well.

At Doncaster, I gave Sam Johnstone his debut after taking him on loan from Manchester United.

Sometimes, given the budget I was working with, I had to turn to youngsters, so there was a bit of luck involved.

But I was also very keen on promoting young players. At both Oldham and Doncaster, I would always ask the youth team manager which player had trained best that week. Not necessarily the best player; I wanted the one who had trained best. I’d take them up to the first-team squad that week, and let them experience a professional training environment.

That meant the young players knew that everyone had a chance. I had no problem with throwing a youngster into the first team if they were good enough. The others could then see someone succeeding and knew that, if they put the effort in, they would get a chance as well. So, I was always aware of the best players coming through.

“In the 93rd minute, the whole stadium fell silent. I still get a shiver thinking about it now”

At Doncaster, there were times when I needed the youth team players – badly.

I took over there in 2013, and faced some huge challenges right from the start. There was a takeover that dragged on into the start of the season; it meant I couldn’t sign players, because we didn’t know what budget we were working to. Then there were also players already in the squad who I didn’t really want but couldn’t sell.

Doncaster had just been promoted to the Championship, and I came in to try and keep them there. If the takeover had gone through, I’m sure we would have managed it. But, with the lowest budget in the whole division and those restrictions I mentioned, it was too tall an order.

We came so, so close to doing it, though. I still feel sick now when I think about how we got relegated.

On the final day of the season, we were playing away to Leicester – one of my old clubs, who had already been crowned champions – needing to match Birmingham’s result to stay up.

There was a party atmosphere at the King Power Stadium. The Leicester fans were celebrating promotion and they were also singing my name. “Dicko’s staying up” was being sung in the stands. They wanted us to survive.

We went 1-0 down in the 75th minute, but Birmingham were losing 2-0 at Bolton so we were looking good. Both sets of fans were singing my name.

But Birmingham pulled one back. And, in the 93rd minute, the whole stadium fell silent. I still get a shiver thinking about it now. It was horrible.

My assistant came out to tell me Birmingham had scored, but I already knew. I could tell. A few seconds later, the final whistle went. We’d been relegated on goal difference.

“I found out quickly that being one of the best youngsters in Scotland meant nothing at Arsenal”

There were certainly things I could have managed better, but to take that relegation battle down to the final day – to the final minute, even – was an achievement in itself. There were teams like QPR, with budgets of £80m, for us to compete with. We shouldn’t have stood a chance, so for us to come so close was amazing.

That experience showed me how fickle football is. I’d been approached by four good Championship clubs over the course of that season; people who had been impressed with how my little Donny side were acquitting themselves against the bigger boys. They were impressed with the football we were playing.

Then, after that goal for Birmingham sent us down, I heard nothing. Staying up would have been the biggest achievement of my career. Goal difference was all that prevented it, but the offers dried up.

Football can be a tough place to succeed. I learned that very early on in my playing days.

Moving down to London from Livingston aged 16 was a bit of a culture shock for me. I’d just scored in a World Youth Cup final in front of 50,000 people. I thought I was a pretty big deal.

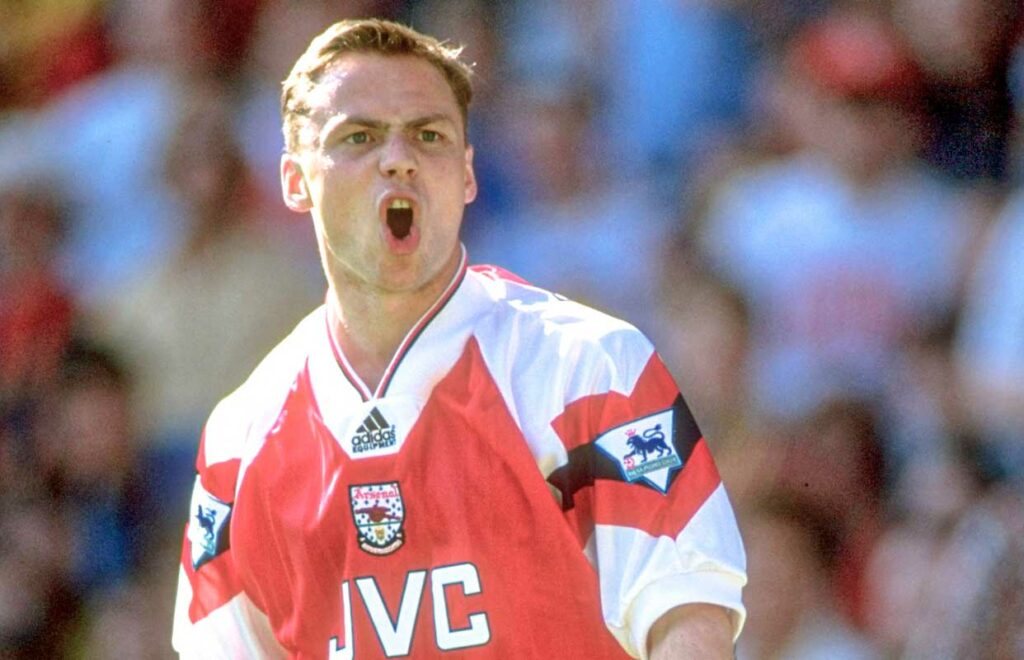

Then I got the move to Arsenal (below), and I really struggled. I found out very quickly that being one of the best youngsters in Scotland meant nothing down there. I was so far behind the others and just couldn’t catch up. Then, one day, my frustration got the better of me.

We played an Under-18s game against Chelsea, and I was on the bench. I wasn’t happy about it, and I was missing home more and more. I came off the bench, and two minutes later I was chasing a ball in the channel when I did something stupid.

I had a five-yard head-start on the defender, and he just breezed straight past me. I didn’t know what to do, so I just booted him. It was just a silly, angry reaction.

Pat Rice was in charge of the team, and he took me straight off again.

“They told me in no uncertain terms that my behaviour was unacceptable”

“We’ll talk on Monday morning,” he said as I walked past him.

That was Saturday, so that night and Sunday night I barely slept. I was sure they were going to send me back home.

My dad had been adamant that I go to Arsenal in the first place, when I hadn’t really wanted to leave Scotland. All that weekend, I was just thinking: “I can’t let my dad down.”

I went into the meeting on Monday, and Pat Rice, George Graham, Theo Foley and Stewart Houston were all there. This was obviously a big deal!

They told me in no uncertain terms that my behaviour was unacceptable. I was ready to be told I was going home.

Instead, George simply asked me: “Do you realise why you’re here?”

I had no idea how to answer; I couldn’t think of anything to say. George answered for me.

“You’re here because you’re different. Stop trying to be someone else. We signed you for being you, so work hard on being you and doing the things you’re good at. If you try to be someone else, it won’t work. If you try to be Paul Dickov, you’ll have a very good career.”

Everything changed after that. I got my head down and worked my way into the first-team squad.

“George Graham had a soft spot for me. He'd come to London at a similar age and I think he wanted me to succeed”

I got to play with some sensational players at Arsenal. I was learning all the time from the other strikers. Ian Wright, Kevin Campbell, Alan Smith, Paul Merson and Dennis Bergkamp. It was great company to be in.

I used to just watch Ian in training. He celebrated each goal like he’d won the cup. His dedication was something else, too. He’d stay behind, just blasting balls into the goal on his own. He taught me that nobody is good enough to think they cannot improve, and that’s why he put the extra work in.

I was also training against Tony Adams, Steve Bould, Martin Keown, Lee Dixon, Nigel Winterburn and David Seaman. It was fantastic.

I was one of the least talented members of the squad, but I worked harder than anyone else. I had to prove myself, and that’s why I succeeded.

Without that conversation with George (below), and the footballing education I got at Arsenal from him, the other coaches and the players, I wouldn’t have become the player – or the coach – that I did.

George had a soft spot for me. He’d come to London at a similar age when he joined Chelsea, and I think he wanted me to succeed – so that might have played a part in him giving me another chance. He, Pat and George Armstrong pushed me really hard.

The expectation was just that we gave 100 per cent in every session. As long as you did that, George would look after you. The players at Arsenal took care of each other, too.

There was more stability at Arsenal than I experienced elsewhere, particularly compared to my next club.

In my first six months at Manchester City, after I joined in 1996, I had five different managers. It was a shambles.

“I could run and run, and defenders struggled with that”

I signed with Alan Ball on a Friday. He’d been sacked by the Sunday.

Asa Hartford, Steve Coppell and Phil Neal followed, and quickly left. Then Frank Clark took over for a couple of years, but the club was in a downward spiral. It wasn’t until Joe Royle arrived in 1998 that things settled down.

The problem was that each manager had been allowed to bring in a few players, so the squad was absolutely massive; full of unwanted players. There were more than 50 players there, and loads of them were unhappy. They’d been brought in by a manager who had left straight after.

Joe managed things brilliantly, though. He chose to help the players he didn’t want by trying to find them moves that would suit them. That helped balance the books and lifted morale, too. He was a master of man-management and led us to back-to-back promotions. He got the club back on track.

I loved playing with Shaun Goater at City. Our partnership worked really well. We used to joke that I would do all his running and he’d just stick it in the net – but it worked. We had a lot of success together.

I was fortunate to be naturally very fit. I could run and run and run, and defenders struggled with that. I would chase anything.

That natural fitness allowed me to extend my career into my late 30s. When I first got the job as Oldham manager in 2010, it was actually as player-manager.

For a while at the end of my career – in spells at Leeds, Leicester and Derby in particular – I had roles as a senior pro in the dressing room. I was more than a player to the manager.

“as a manager, you have to be a psychologist, a financial advisor, a friend and more”

But it was completely different when I got the Oldham job. I found combining the roles of player and manager pretty difficult at first, to be honest.

Looking back, and talking to some of my players from the time, I probably should have played myself a bit more than I did. My assistant, Gerry Taggart, wanted me to play every week, just because of the influence I’d have had on other players around me.

But I couldn’t train all the time because of my other responsibilities, and I didn’t feel it was fair to the players to just pick myself.

I would put myself on the bench, but very rarely brought myself on. I was so engrossed in the game that I’d forget I was an option. My head was all over the place.

When you’re thrown in at the deep end, you very quickly learn that, as a manager, you have to be a psychologist, a financial advisor, a friend and more. It’s tough, and too much to do as well as being a player.

I wanted to try and help my players on and off the pitch, and I loved doing it. Once I got the chance to be a manager, my mind was on that, and ending my playing career became easier.

I enjoyed learning from my teammates as a player, and I’ve always loved helping out younger players once I was the more experienced player. So that side of being a manager came naturally to me. I was also used to working hard, and that came being a manager, too. Right away, I was ready to put in the hard yards.

PAUL DICKOV