thomas tuchel

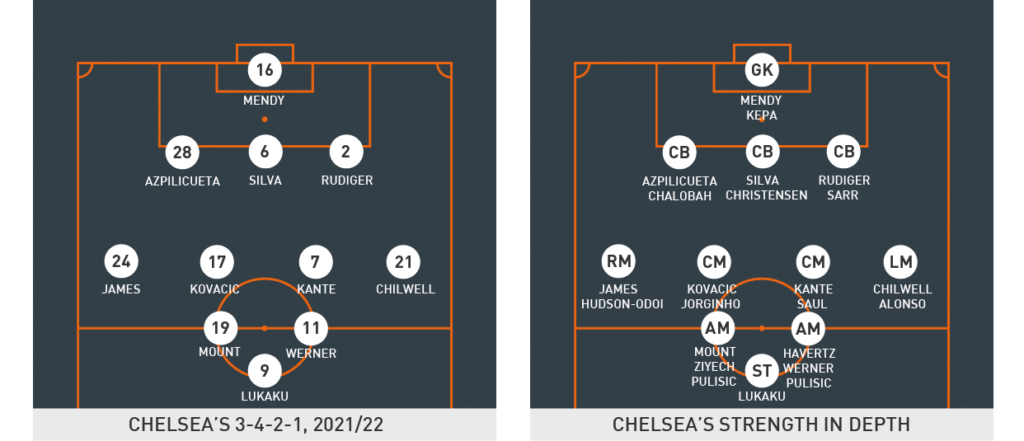

Chelsea, 2021–2022

Pursuing a manager capable of transforming the expensively assembled squad led in 2018 by Neymar, Kylian Mbappé and Ángel Di María into contenders for the Champions League, Paris Saint-Germain turned to the respected Thomas Tuchel. Admired for his influence when succeeding Jürgen Klopp at Mainz and then Borussia Dortmund, and for reshaping what was so distinctive a team, the then-44-year-old inspired an improvement that for the first time took PSG to the final of the Champions League.

Like Julian Nagelsmann, Tuchel was identified by none other than the influential Ralf Rangnick as a coach of promise and quickly became one of Europe’s leading managers. "He’s a fantastic coach, you can really see his influence," Klopp said of his compatriot. "I know many people who have worked with him and respect him immensely. You cannot aim for the Champions League only by spending money, it does not work. It takes a good organisation, all the other clubs are not blind, we also do our job well so we need the right tools at the right time. Thomas obviously has them."

Chelsea, perhaps in a similar position to PSG following their recruitment of Timo Werner, Kai Havertz, Hakim Ziyech and more, took advantage of his departure from the French capital in December 2020 to appoint him as the successor to the popular Frank Lampard. Like José Mourinho, Antonio Conte and Carlo Ancelotti before Lampard, the German will also unquestionably be tasked with delivering the Premier League.

Playing style

In his two previous high-profile positions, at Dortmund in 2015 and then PSG, Tuchel was appointed to succeed two respected and successful managers in Klopp and then Unai Emery, and his task was therefore to evolve the strong teams he was inheriting. He retained Klopp’s 4-3-3, which also often became a 4-2-3-1, but where Dortmund had been a transitional side, under Tuchel they placed an increased emphasis on possession. With the lengthier build-up play that involved, their players had more time to rotate into different areas of the pitch and to maintain fluidity in their attacks.

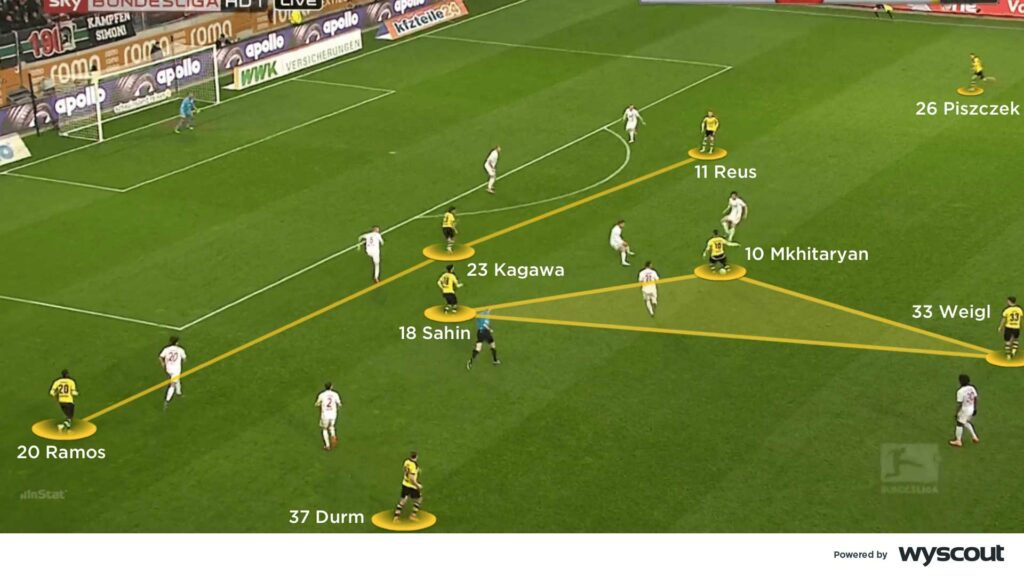

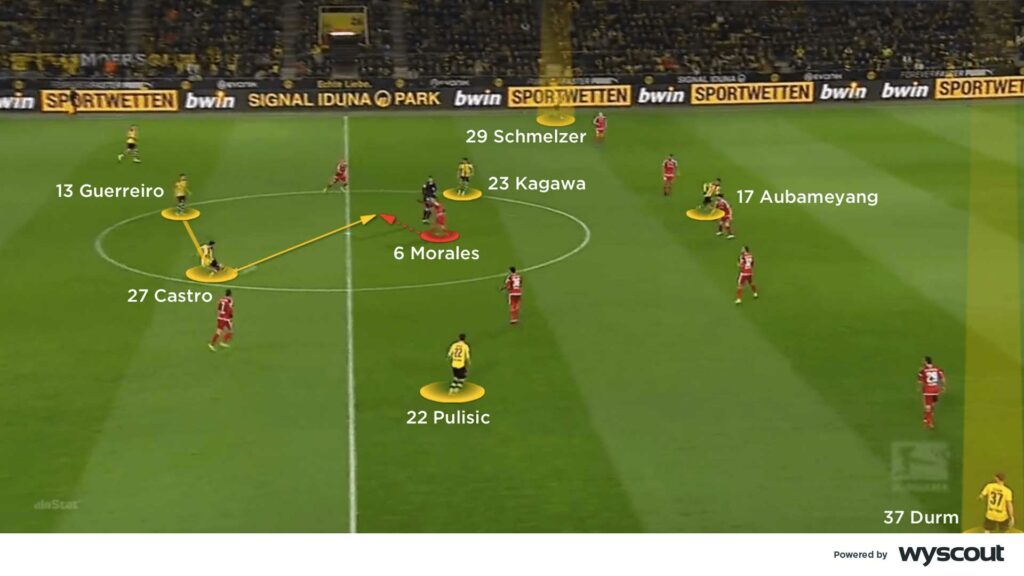

Their central attacking midfielders, playing in front of a single defensive midfielder, were particularly influential. Marco Reus relished operating in an advanced position, and he would rotate with Christian Pulisic and Henrikh Mkhitaryan behind Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, who remained fixed as their central attacker. Aubameyang was consistently supported by their two wide forwards and two attacking central midfielders; Dortmund’s full-backs would also advance, but didn’t necessarily provide overlapping runs.

Their improved grasp of possession meant that they often succeeded in restricting opponents to their defensive half, and was complemented by an energetic press, which contributed to them regularly encountering lower blocks (above). When, from towards the conclusion of his first season there, Tuchel began to experiment with the use of a back three, he demanded regular changes in shape – occasionally mid-match – but at the risk of their wing-backs sometimes becoming stretched.

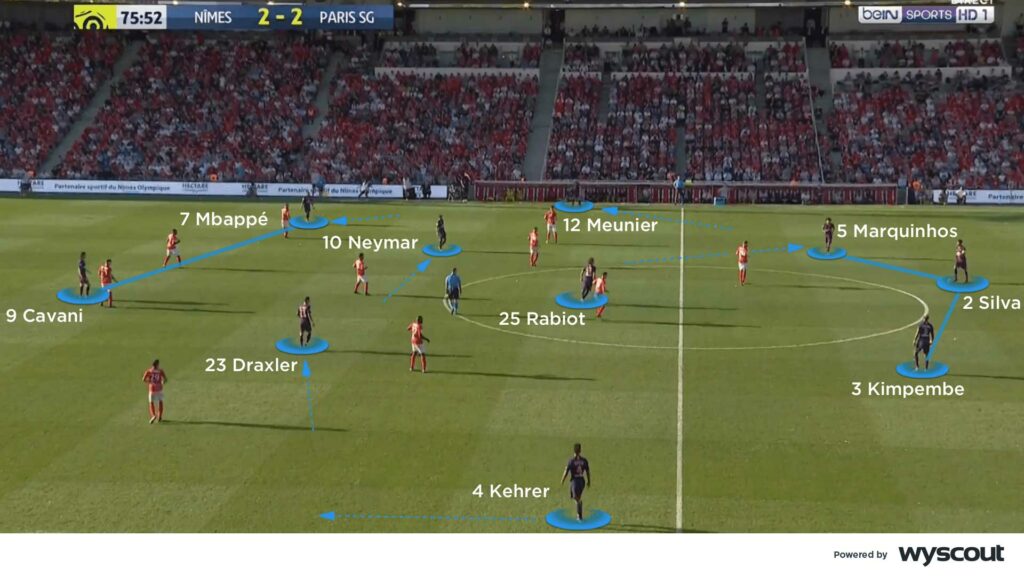

In Paris, Tuchel similarly retained Emery’s 4-3-3 and 4-2-3-1. As at Dortmund, he demanded rotations from those in central areas, but their attacking width was instead provided by their advancing full-backs, encouraging Neymar, Mbappé and others to remain in narrower positions, closer to Edinson Cavani, their central striker. His central midfielders also therefore had to offer greater dynamism, and to demonstrate an awareness of the spaces that their full-backs had left, as well as when to withdraw into central defence and temporarily form a back three – largely because so many Ligue 1 opponents could only threaten them during moments of transition. Marco Verratti, Adrien Rabiot and Marquinhos each proved capable of doing so.

During his first season there he also adopted the use of a more defined back three, wing-backs (above) – Dani Alves, Thomas Meunier and Juan Bernat were most commonly those wing-backs – and a double pivot. Further forwards, Cavani was supported by number 10s in Neymar and Mbappé. When Mbappé advanced into a position alongside Cavani, one of those forming their double pivot advanced into the space he had vacated to ensure that both inside channels remained covered.

Regardless, Tuchel consistently favoured a back four as PSG progressed to the Champions League final in 2019/20. They defended with either a 4-4-2 or 4-3-3, and attacked with a 4-2-2-2 in which Neymar and Di María operated as number 10s in front of a double pivot and behind the penetrative Mbappé and the focal point provided by either Cavani or Mauro Icardi.

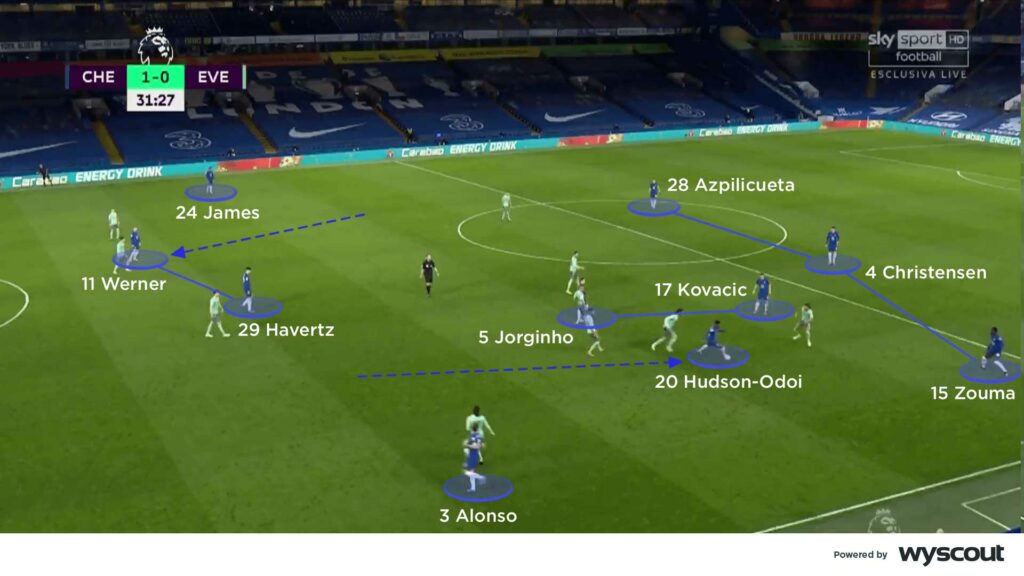

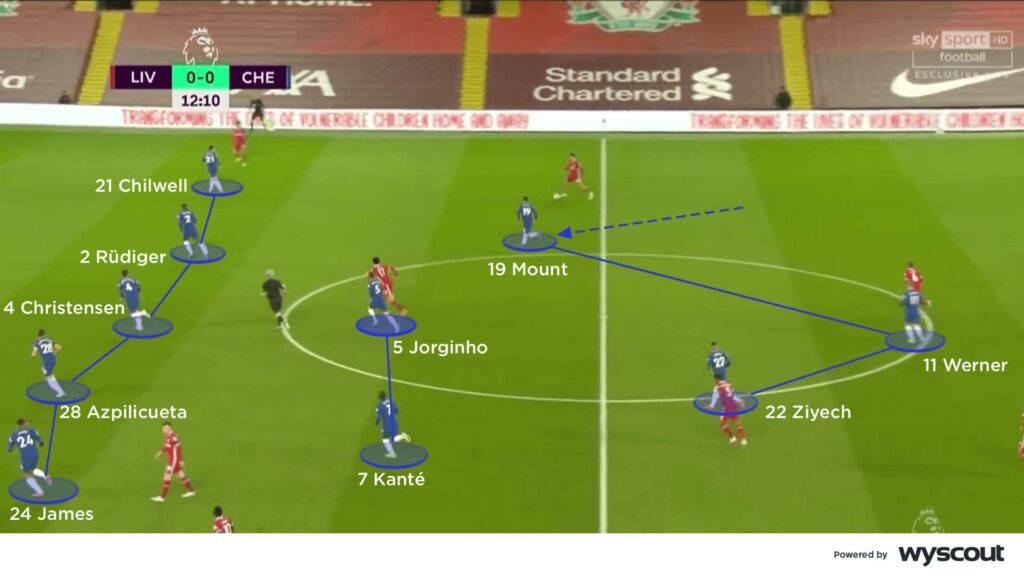

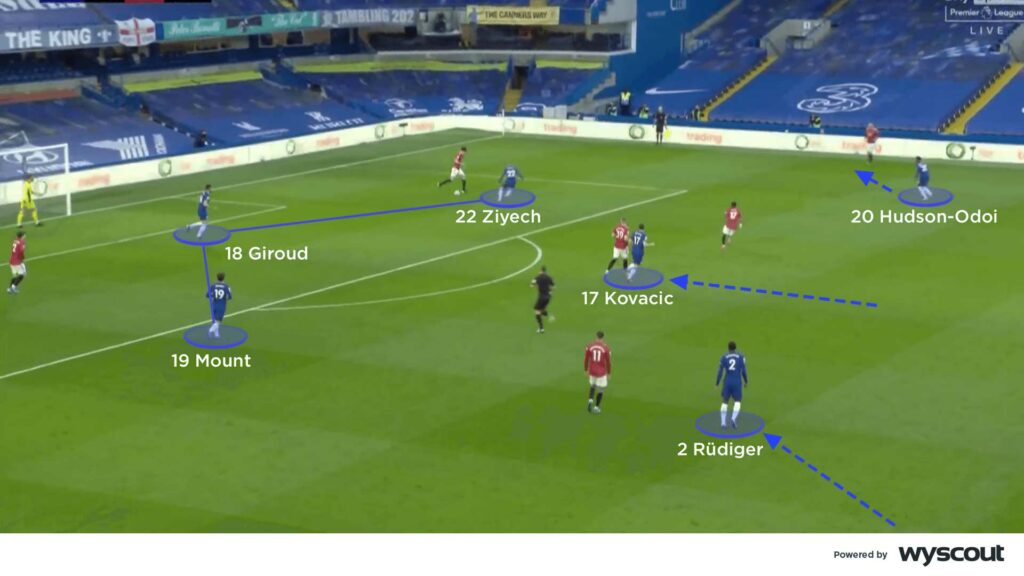

Since arriving at Chelsea, Tuchel has almost entirely favoured a back three, and either the use of two number 10s in support of a lone striker, or a front two (above) supported by one fewer attacking midfielder. The options at his disposal and opponents applying tactics intended to negate, specifically, the system Tuchel has overseen have prompted him to regularly change his attacking personnel and their positioning.

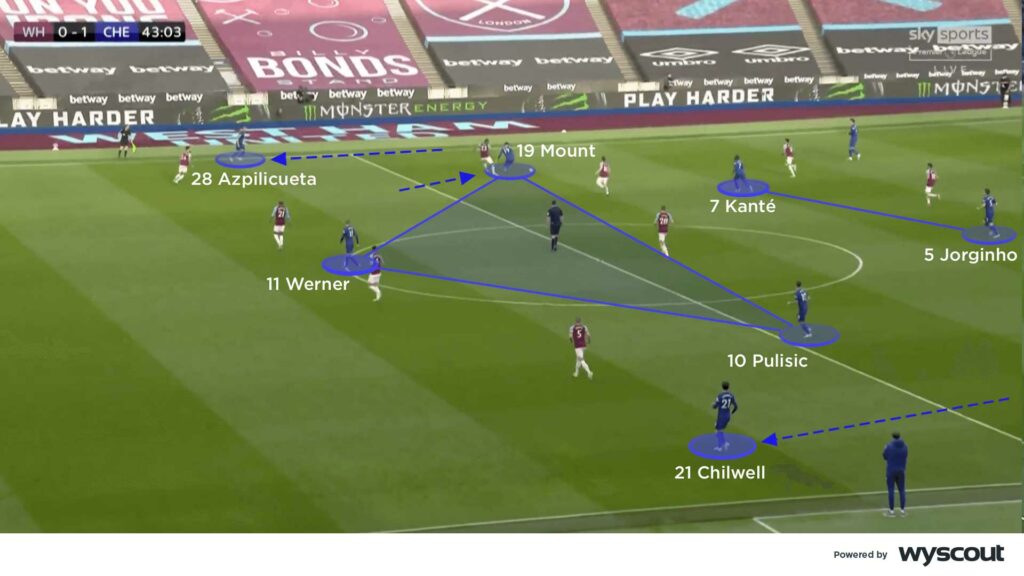

Werner has benefitted from a narrower starting position because of the increased number of runs it encourages him to make through the centre, and often as Chelsea's leading penetrative runner. Ziyech, Havertz, Mason Mount and Pulisic move to towards the ball from between the lines. There therefore remain occasions when Chelsea lack sufficient sources of penetration behind opposing defences, but their attempts to build possession are improved, particularly given their defensive midfielders are often aggressively pressed. One attacking midfielder withdraws into the spaces vacated by that press being applied, creating forward passing options, and a method of resisting it.

Retaining possession for lengthier periods away from that pressure has also been used as much as a defensive strategy intended to undermine opponents’ attacking potential as it has to enhance their own. Chelsea’s wing-backs are increasingly advancing to alongside or even ahead of their attacking midfielders (above), both providing a crossing threat from wide territory and drawing opposing full-backs out of position, in turn creating increased space through the inside channels for their attacking teammates’ runs in behind.

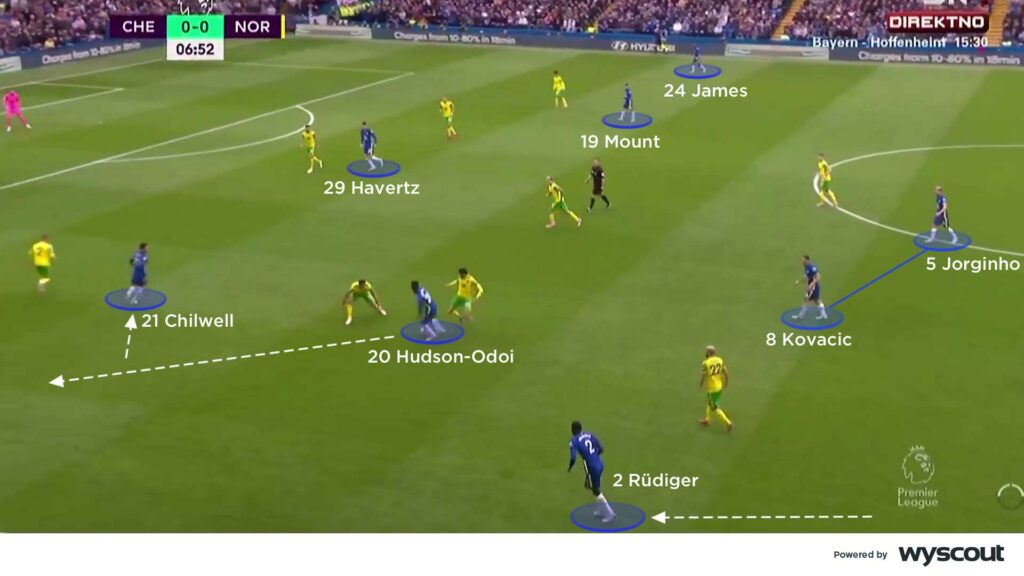

Their two wider central defenders have instead become those expected to provide secondary wider support. César Azpilicueta continues to feature as their right-sided central defender from where, as under Conte, he advances through the inside channel; towards the left Antonio Rüdiger demonstrates greater caution and, unlike Azpilicueta who does so while under pressure and seeks to support into the final third, instead only carries possession forwards when space exists. The two defensive midfielders consistently selected provide support from behind the relevant wing-back, but are instructed to prioritise central play when possession is being built in the defensive half. They have consistently impressed in their judgement of when to move into defence or adopt wider positions; combinations between them and the wing-backs and wider central defenders alongside them have regularly contributed to progressing possession, as have more direct passes to those between the lines.

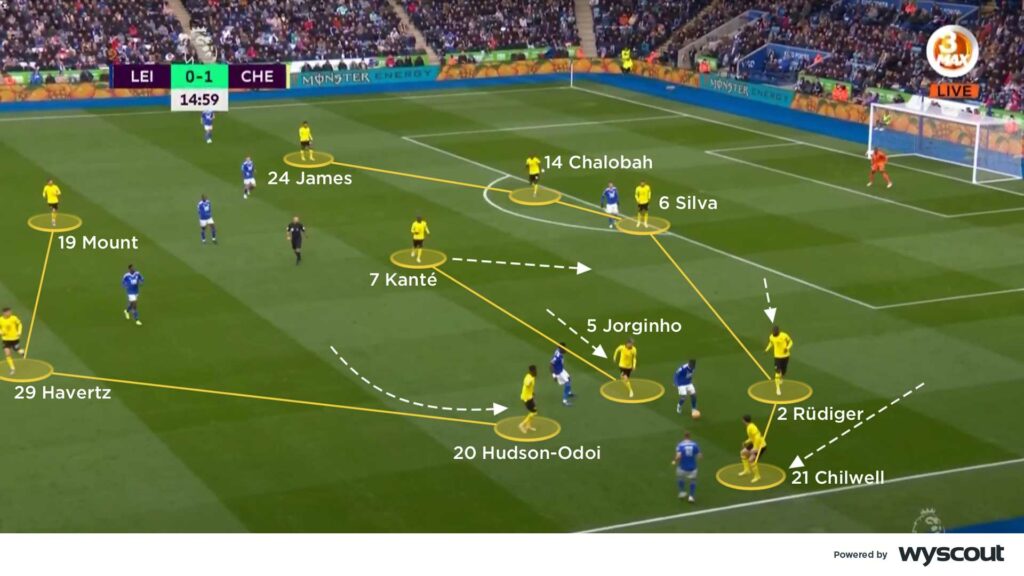

Towards the end of 2020/21, as his squad continued to adjust to his methods, Tuchel introduced rotations between his wing-backs and attacking midfielders (above). Reece James, Marcos Alonso and Ben Chilwell increasingly advance into attacking, central positions where they often rotate with the 10 closest to them in addition to, similarly to a traditional wing-back, continuing to provide width, crosses, and support through wide territory – an attacking pattern that creates space in central areas by drawing opposing midfielders or central defenders from their defensive positions. Complemented by Chelsea's defensive midfielders playing passes from midfield and into Romelu Lukaku or those making supporting runs, they are proving more successful at accessing their central striker and therefore providing a greater threat on goal.

When possession is built towards one side of the pitch, the far-side wing-back often proves capable of advancing with freedom into the final third because of the defensive attention being given to their front three. Those same rotations also contribute to increased space for Chelsea's wider central defenders to carry the ball into or to provide support from to those in the inside channels – Rüdiger, from the left, and Trevoh Chalobah, from the right, have both proved effective at doing so – and to drawing opposing full-backs infield, in turn giving Tuchel's team greater potential when wide.

Defending and pressing

Tuchel’s flexibility with his teams’ shape has inevitably contributed to further variety when they are out of possession. That his full-backs didn't advance at Dortmund meant them instead prioritising covering the inside channels, and with the single pivot at the base of their midfield remaining central, their wide forwards and attacking midfielders being given freedom to attack.

If they instead used a back three and wing-backs, those wing-backs’ higher positioning meant reduced cover around that single pivot during turnovers of possession; even if the additional central defender made them stronger there, their reduced numbers in midfield made it harder to regain the ball further forwards and to prevent their opponents from advancing. Their double pivot (above) gave them increased defensive strength, but came at the expense of an additional attacker, and therefore did little to prevent defensive transitions.

PSG's previous defensive structure relied on their central midfielders preventing transitions in the central areas of the pitch and then covering the spaces that were vacated by their advanced full-backs. Their ability to restrict many opponents to their own half for lengthy periods meant that that tactic proved effective, but their strongest domestic and European rivals succeeded in progressing through their mid-block because of how easily they overcame their first line of pressure. Opponents playing around or over PSG's shape troubled them; relatively straight passes over their full-backs (above) or inside them regularly led to their opponents getting in behind. They also struggled when defending against crosses from wide areas, when their full-backs were too isolated in pressing the wide areas.

Before Mauricio Pochettino's appointment, their more recent use of an out-of-possession 4-4-2 offered improved cover for their full-backs, which particularly counted when they resisted pressing high and instead remained in a mid-block. That shape also evolved into a 4-3-3, through one of their wide midfielders advancing when Tuchel demanded that they apply a high press and attempt to force opponents into longer passes. That 4-4-2 similarly complemented their in-possession 4-2-2-2. Their full-backs advanced, and their wider midfielders adopted narrow positions to support through the inside channels. The double pivot, aided by the increased cover in wide areas, made them harder to break down, and the personnel in there gave them more aggression.

Chelsea’s out-of-possession shape often involves them defending with a back five, via their wing-backs – most consistently James and one of Alonso or Chilwell – withdrawing into deeper positions (above). That their double pivot is retained ensures that they have numbers during periods of building possession in the defensive half, meaning losses of the ball are swiftly followed by it being surrounded with defenders, whether wide or in central areas.

Their attacking structure, similarly, means them being able to offer sufficient cover when the ball is conceded in the attacking third, and therefore being difficult to counter. Their three central defenders are capable of both pressing and delaying wider transitions without sacrificing cover in their defensive line, and their two defensive midfielders cover and support the territory in front of them, blocking potential switches of play – those attempted via shorter passes – and remaining available to withdraw further. That double pivot also covers, if required, the wider spaces when there is already a back five behind them, via one covering across and the other remaining in a central position, increasing Chelsea's defensive strength.

As when they have the ball, their front three have been used in a variety of positions that determine whether they are defending with a 5-4-1, 5-3-2 or 5-2-3 – as demanded by the nature of their opponents’ attempts to build play. There are times when they withdraw to as far as alongside their defensive midfielders; most commonly, they work to force the ball wide, and to screen and cover access into their opposing defensive midfielders while providing secondary cover from behind the ball, particularly from the centre of the pitch.

When Chelsea defend and press from further forwards (above), two attacking players prioritise their opposing defensive line and are supported in doing so by their wing-backs, who take the full-back opposite them. When those wing-backs advance, their defensive midfielders move to cover the wider spaces, so the spare attacking midfielder works to block access into midfield. An alternative approach involves one of their defensive midfielders advancing and being joined in doing so by a wider central defender, and therefore the wing-back alongside that defender remaining deeper and the other defensive midfielder covering behind him.

A pressing trap more recently introduced has proven effective because of the compactness they offer in central territory, and because of the numbers that work to force possession wide, regardless of their defensive shape. Typically their wing-backs press, with aggression, towards the wings, and the closest central defender follows them while remaining braced to move through the relevant inside channel. Against attacks through the inside channels, Chelsea's wider central defenders assertively stray from their defensive line to press alongside the double pivot in front of them, and their wing-backs therefore tuck infield to provide defensive cover.

Against wider play, however, their defensive midfielders move across to cover against attacks infield and to between the lines. With the furthest of Chelsea's two central midfielders ready, when required, to withdraw into defence to provide additional cover from behind the central defender who has advanced to press, the closest 10 moves across to negate backwards passes and force possession wide, where others then swarm the ball and the in-possession player to make regains.