timo werner

Chelsea, 2020–

Profile

Timo Werner had become hugely sought-after by the time Chelsea won the race to sign him in the summer of 2020. Shining for Europe’s most exciting up-and-coming side – in 2019/20, that team was RB Leipzig – is a sure-fire route to a big-money transfer, so it was no surprise when Chelsea agreed to pay £47.5m to take him to Stamford Bridge. Having completed a fourth consecutive high-scoring season at Leipzig, with 2019/20 his most productive yet, Werner was hot property. Across Europe’s top five leagues, only Ciro Immobile, Robert Lewandowski and Cristiano Ronaldo scored more than Werner’s 28 goals.

His early days at Chelsea under Frank Lampard did not bring as much success or as many goals as the end of his time in Germany, but a change of role under Thomas Tuchel has resulted in a happier and more settled-looking Werner. “Every manager is different in how he wants us to play,” said Werner. “[Tuchel] gives us a lot of ideas. Now I play as a left number 10, not a left winger, so I have more space for my runs in the middle and can play behind a striker, or with a number 10 behind me as a second striker. It’s very good for me.”

Tactical analysis

Werner’s primary threat is in front of goal – he scored 89 goals in 147 Bundesliga and European games in four years at Leipzig following his €10m move from VfB Stuttgart in 2016. In the age of Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi, any ratio lower than a goal a game sounds less impressive than it should – but few players ever maintain Werner’s scoring rate of a goal every 1.6 appearances over a sustained period at the top level. Aged just 24 at the time of his move to Chelsea, he deserves extra credit for having done so at such a young age.

Werner is one of the quickest forwards in football and, particularly in the early part of his career, he did much of his best work on the shoulder of the last defender. It was perhaps inevitable then, that as his status grew and opponents became more accustomed to his threat, defences chose to drop off and reduce the space they left in behind. When that first happened Werner struggled, appearing too one-dimensional in his approach and still looking to make runs in behind that, with space limited, forced teammates into rushed crosses or overambitious through balls that rarely succeeded.

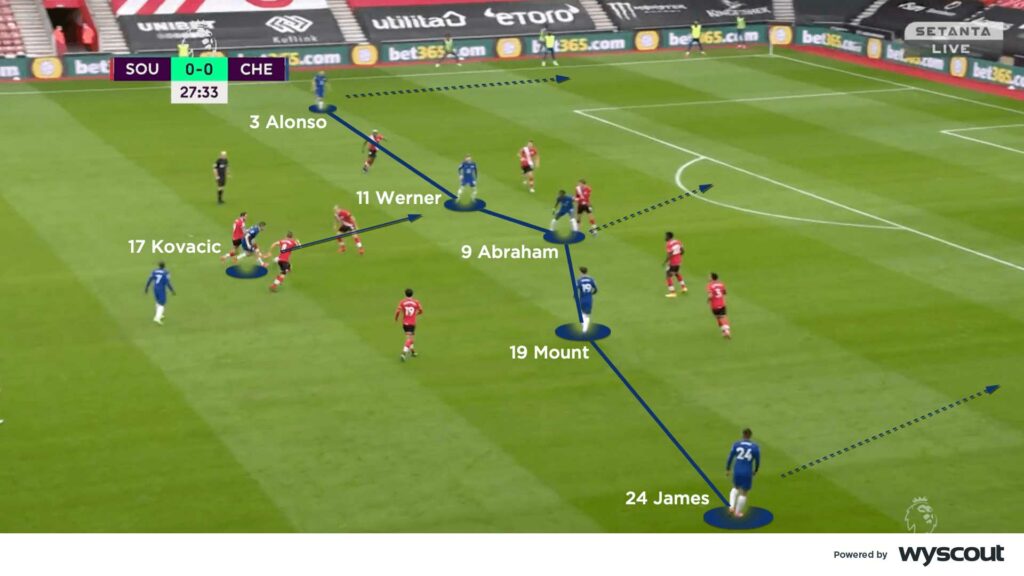

His manager at Leipzig, Julian Nagelsmann, recognised that Werner had to develop to get more involved in build-up play “if he wants to be one of the world’s best”. Werner has since done far more of his work between the lines, and he is comfortable coming deep to collect the ball to create for others. When he did so for Leipzig, his movement invited the wing-backs in Nagelsmann’s 3-4-3 to run beyond him, and he tended to turn out towards the wing and away from more crowded parts of the pitch. He is now more adept at receiving to feet and turning into midfield to spread play or to look for a more advanced teammate, so he is more confident receiving in central positions (below).

Werner regardless remains at his best when he has the opportunity to run in behind. When playing as a centre-forward he pulls towards the left, usually between centre-back and right-back so the centre-back can’t see him; if he is playing as a left-sided attacker, as he has done on plenty of occasions for both Leipzig and Chelsea, he often makes his run on the outside of the right-back. Given he is as fast as he is, he doesn’t need to start as high as other forwards, so he leaves himself less at risk of being caught offside and uses his pace rather than the timing of his runs to leave defenders behind. His finishing could do with improvement – his decision-making when one-on-one is sometimes a little too hesitant, meaning he can miss the best moment to finish by delaying too long. As a result, a few too many of his chances are wasted.

Werner has become more difficult to track due to the greater variety in his movement. Defenders are constantly tested as to whether they should follow him into deeper positions or pass him on to a midfielder – and, when he drops off, he creates space for others and also often loses his marker, meaning he is often free when he later bursts forwards to join attacks from deep.

Role at Chelsea

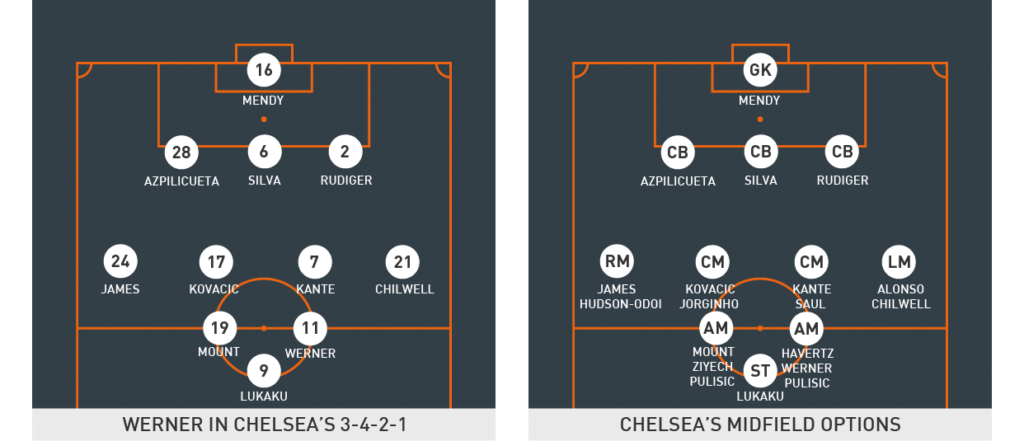

Under Tuchel, Werner has mostly played as a left-sided attacking midfielder behind a lone centre-forward, but against better opposition – where there is likely to be more space behind to run into – he has played as the lone striker. When he plays as one of the two number 10s in Tuchel’s 3-4-3 he comes infield more than he did as a left-sided attacker in Lampard’s 4-3-3 and – in the same way he did for the wing-backs at Leipzig – invites their wing-backs to overlap. He spends significant periods of the game in central positions rather than wide, looking to get on the ball in between the lines and turn and drive at the opposition's defence. As one of the two narrow 10s who stay close to the centre-forward providing their width is not his job; it is instead the responsibility of their wing-backs (below).

Opportunities to run in behind from that position are quite rare and, when they do appear, he has struggled to get through in a central lane. He is therefore often forced into shooting from tight angles or looking to find a teammate in a better position – which at least in part explains why he has struggled for goals despite improved performances in the early part of Tuchel’s reign.

Werner has, however, looked far more dangerous in behind against teams that push forward and leave a little more space for him to break into. Even then he is having to act on instinct more than he did at Leipzig, where he often had time to set himself in front of goal – and that has led to him snatching at chances – though the fact that he is usually playing off a striker means there is less pressure on him to get into those positions and score goals.

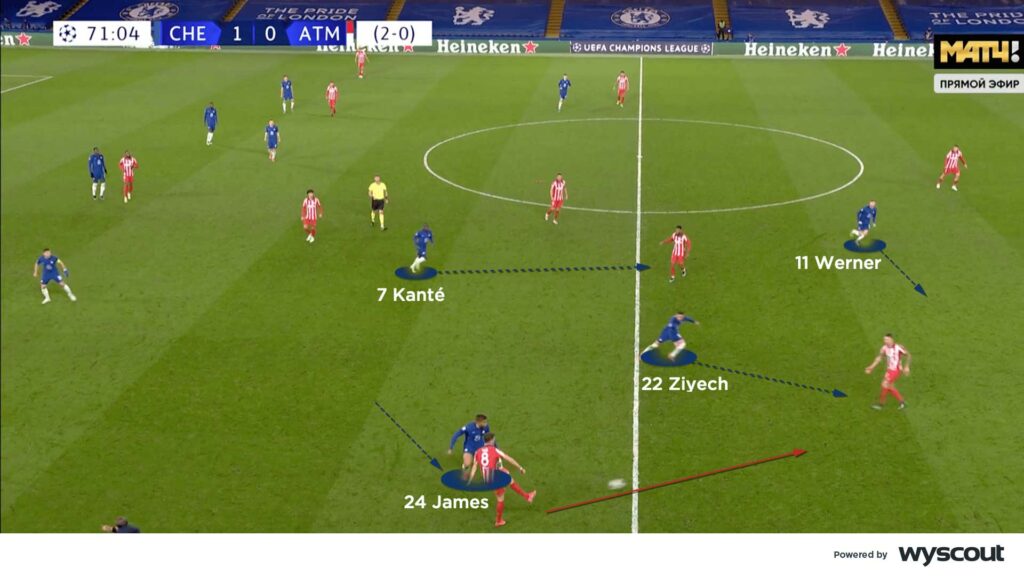

Tuchel has prioritised strengthening their defence since taking charge at Chelsea, and Werner plays an important out-of-possession role, working hard and pressing with intelligence. His team looks to crowd an opposition's full-back or centre-back – sometimes a specific player – by committing more numbers to a small area of the pitch than the opposition have in that zone. Their risky approach leaves players available for a switch of play if an opponent can find space to play one, but Chelsea's players press with cohesion and aggression, and Werner’s speed and clever movements make him particularly useful. Whether he is one of the players engaging a direct opponent or cutting off a route for the opposition to pass their way out of trouble (above), he does so with total commitment.

Werner is also important at attacking transitions because as soon as Chelsea regain the ball, he sprints forwards at such speed that he carries an almost immediate threat to the space that the opposition have left in their structure.

There is still work to be done and elements to be added to the Germany international’s game – not least a few more goals – if he is to prove worthy of the money Chelsea paid for him, but he is still improving and is without question a far more complete striker than he was during RB Leipzig’s run to the Champions League semi final in 2019/20. Tuchel could yet prove the manager under whom Werner can fine-tune his game and join the world’s elite.