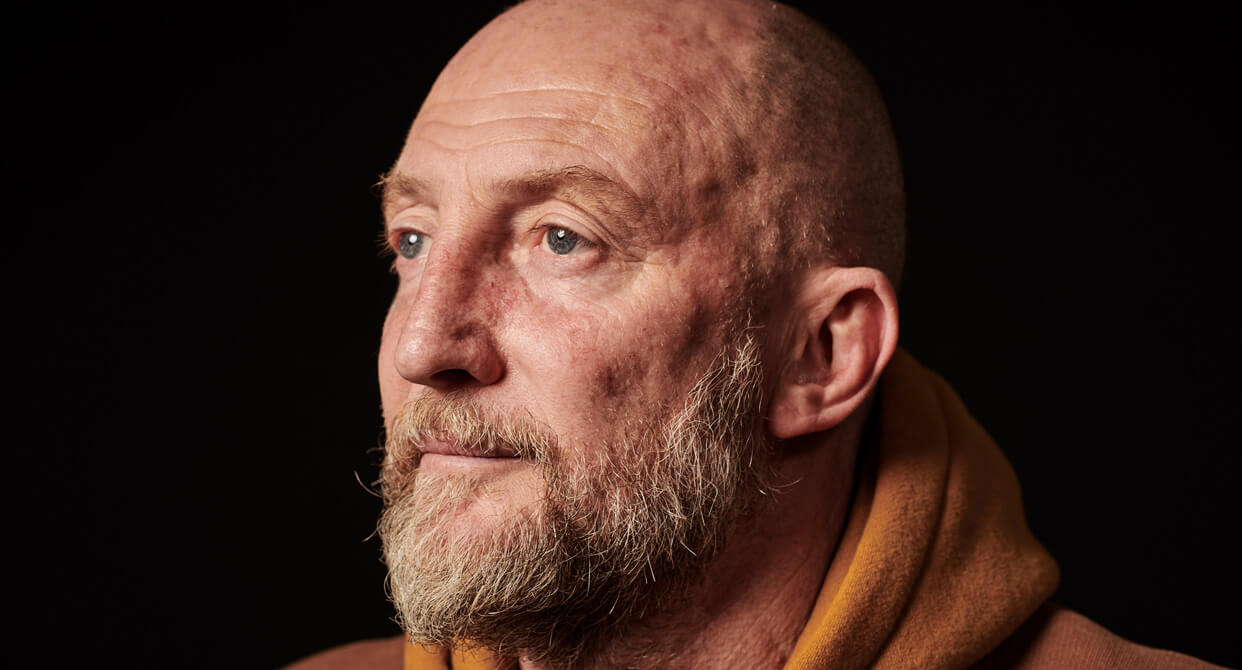

Ian Holloway

Blackpool, 2009-2012

“Football is beautiful everywhere. You haven’t got to play it one way.”

That was my best mate Gary Penrice, telling me to find a new approach. A new attacking strategy.

Or, as he put it: “Get back to being creative, like you used to be.”

At the time, I was out of work. It was the first time in my career that I’d gone longer than a week without a job. Gary told me to use it wisely.

“I’ve watched you lately, and your team just defends. You’ve got your wingers defending. Go and watch Swansea. See how they play. Do yourself a favour. Build. Be creative.”

When the BBC gave me some work doing commentary, it just so happened that they sent me to watch Swansea, then managed by Roberto Martinez, three times. I was blown away by what I saw: they had a right-winger coming back hitting a crossfield ball to a left full-back.

I’m thinking: “What? How can they be that open?”

The more I watched, the more I got excited.

I spent hours writing down my ideas: I move the ball to my right centre-half, get it back to my goalie, move it to my right-back, to my left-back... I had a whole plan of what I thought should happen with the ball. And patterns of sessions – sessions I’d never seen anyone else do.

By the time the Blackpool job came up, I knew exactly what I wanted to do.

My only problem was getting an interview in the first place. When I rang the chairman to put myself forward for it, he wasn’t exactly open to the idea.

“Sorry mate, I don’t want to interview you. Your agent has just asked for some money and I don’t pay agents. Goodbye.”

He put the phone down on me.

I called him straight back: “Who do you think you're talking to?”

“Sorry, who is this?”

I said: “It’s Ian Holloway. You’ve just told me I haven’t got your job. How can you say that when you haven’t met me?”

“Well, I’m not paying your...”

“I haven’t told you you’ve got to pay my agent, have I? Do you want to meet me or not?”

"They’d finished 16th the previous season, but I fully believed they could play the way I wanted to"

A few days later I drove up to see him, and it was like no other interview you’ll ever have in your life. I’d read what the fans were saying about him, so I went for it.

I walked in, went up to the bar and said: “I'll have a coffee. Do you want a coffee?”

He went: “Are you paying?”

“Yeah, I've heard what you’re like. I don’t want that awkward silence when I sit here and wait and you don’t want to pay. I’m paying.”

So that was how it started.

Then he went for it: “I’ve got some questions for you.”

I said: “No, I’ve got some for you first, before I decide whether I want to work for you or not.”

He answered every one of them fantastically well. I couldn’t argue with it.

They’d finished 16th the previous season, but I looked at the team before the interview and I fully believed they could play the way I wanted to.

At the club, the attitude was almost one of acceptance: They thought they were doing well.

I questioned it: “Why is that doing well? Why can’t you set your sights higher?”

I explained the way that I wanted to play. Told them how players at the top level are always focusing on the next thing. When they passed the ball, they didn’t wait. They ran somewhere else. And the player they passed it to knew to do the same.

“I want you to be able to do that. So, I'll try and bring you a way of thinking about the game that can make that possible.”

"Normally, you’re lucky if you’ve got four in a team who are holding the others to account. I had about 10 of those"

More important than that was the other people I had with me. When I told my assistant Steve Thompson what I wanted to do with the training, he said: “No problem, we can implement that. But what about the rest of the day?”

“I want a proper warm-up.”

“I can do that.”

“And I want something before the warm-up that makes them a better player. I want them moving. I want them thinking. And I want them to do that every day.”

I had one other instruction for the whole team. No moaning.

No negatives. The place had been riddled with them, and it was something I was determined to change.

For the first month or two I had to keep on top of that: “Oh, that’s a negative, shut up. I’m not coming all the way up here, leaving my family behind, to worry about negatives.”

I told them that if I thought we needed something, I’d go and see the chairman and try to get it. If I couldn’t get it, then at least I’d tried.

“So shut up. Not interested.”

After the first few months, the positivity started to gather momentum. That carried over into training, where Tommo had them playing in little boxes. They’d do one-touch, two-touch and three in there sometimes.

Then we added extra balls in: “There’s two balls, you’ve got to keep that going. There’s three balls... you’ve got to think quicker.”

Every morning, they couldn’t wait to get out there.

I was lucky at Blackpool – I inherited so many fantastic people. Normally, as a manager, if you’ve got four in a team who help you train properly – who are holding the others to account – that’s great. I had about 10 of them. That made such a difference. Especially as we were all on awful money.

There was a huge bonus structure in place, though. If we succeeded as a group, the players got a major bonus that would almost pay them what some of the other clubs in the division would.

That figure was my motivational carrot.

Before some games, I’d just write the amount of money on the top of the board: “Do I need to say any more lads, or what? Think of that, and what that’s going to do for your family, and let’s go.”

All the tactics were already done, because they never changed. We had a way of doing it. If we were behind, then we had a different way of doing it. We practised it every day and they understood it all.

The beautiful thing was that they all responded to a system that suited every one of them.

"It was as if there was a storm going on outside, but I was in a quiet little area just watching it rage"

As the season went on, I started to sense that we could do something special. But when Neal Eardley picked up an injury with a couple of months of the season to go, I felt desperate. I had no other option at right-back.

That’s when the final piece of the puzzle slotted into place, thanks to my old mate Gary Penrice. He was scouting for me at the time, and knew that Everton had a promising kid at right-back who wasn’t quite ready for the first team there.

The lads in my dressing room were down about Eards’ injury, but the next day in comes Seamus Coleman. Suddenly, the mood lifted.

We are going to do this.

I slept like a baby the night before the playoff final against Cardiff.

The form we were in made me believe that they believed they could do it. I’d never really felt like that in my life before. There was almost a sort of calmness about it – as if there was a storm going on outside, but I was in a quiet little area just watching it rage.

I felt it. This lot can do this. They really can.

That was the message I gave to the players. I talked them up. I talked about how big the club was, and how great it could be.

I reminded them that Stanley Matthews was all over the walls at Bloomfield Road. Morty, Stan Mortensen, was all over the walls. I said: “I want you to be famous, lads. Why can’t you be famous? Why can’t this group of Blackpool supporters remember you for the next 40, 50 years? Why can’t you do something special?”

I think that was the biggest thing I got them to understand.

"Let’s do something. Let’s make a difference"

When I first started coaching, it was all about me. I wanted to be a good coach. I wanted to be a good manager.

It was all I was thinking about: me, me, me, me, me.

But the truth is, at that time, it wasn’t about me. It was about them. I wanted to make a difference to them. I wanted their lives to change. I wanted them to get a promotion. I wanted them to be better players and better people.

I wanted them to understand what being a true teammate meant, and that it didn’t matter what facilities they had to train on. It didn’t matter what we didn’t have.

Stop moaning about all of that. Let’s do something. Let’s make a difference.

And that’s what they did.

At Wembley that day, there was one moment, after the final whistle blew, when Rob Edwards – a wonderful lad who hadn’t played on the day – ran out on the pitch. I watched him grab hold of two or three of his mates, and they were all crying.

All I can remember is him saying: “We did it. We did it. We did it.”

And that will stick with me for the rest of my life. Because I believed they could. And, in the end, they did.![]()