Michael Carrick

Middlesbrough, 2022-2025; Manchester United, 2026-

Michael Carrick is back in the hot seat as Manchester United head coach, appointed until the end of the 2025/26 season following Ruben Amorim’s departure. It is the second time the Englishman has taken on the role, having acted as caretaker manager for three games in 2021. This time round, however, he will have several months at least to make his mark – and it comes after nearly three seasons’ experience as head coach of Middlesbrough.

Carrick was appointed by the Championship club in October 2022, with the team one point above the relegation zone. By the end of the campaign they had finished fourth, only to lose in the playoff semi finals to Coventry City. In his second season they reached the EFL Cup semi finals for the first time in 20 years, but dropped to eighth in the Championship. The following season a 10th-place finish saw Carrick lose his job.

But with Manchester United aiming to appoint a successor to Amorim at the end of the 2025/26 season, they turned to Carrick to take charge in the interim at Old Trafford. Below, our UEFA-licensed coaches have analysed the tactics and style of play he implemented during his time as Middlesbrough head coach.

Short-passing connections

Carrick played a back four at Middlesbrough, in contrast to the back-three used by his predecessor Chris Wilder and brief caretaker Leo Percovich. During his time on Teeside, Carrick’s preference was for a 4-2-3-1 formation, with occasional use of a 4-4-2.

At Boro he swiftly introduced a noteworthy passing style, involving frequent short passes. In his three seasons in charge, Middlesbrough ranked third, fifth and third for total number of passes in the Championship, with similar rankings for passing rate – a measurement of the total number of passes per minute in possession. Even when only averaging 51.7 per cent possession in his second season, Carrick’s side still played a very high number of passes, with close-quarter connections key to their approach.

In build up, Carrick’s Boro looked to dominate the central spaces with significant numbers. Their double pivot connected frequently with the two centre-backs, playing lots of short bounce passes back and forth to manipulate the opposition press, or the opposition first line if they were sat in more of a mid-block. The full-backs would initially stay, before releasing later. It was a short-passing style in central areas that was similar to how Carrick operated as a player – often playing the way he was facing, providing a consistent stream of short passes.

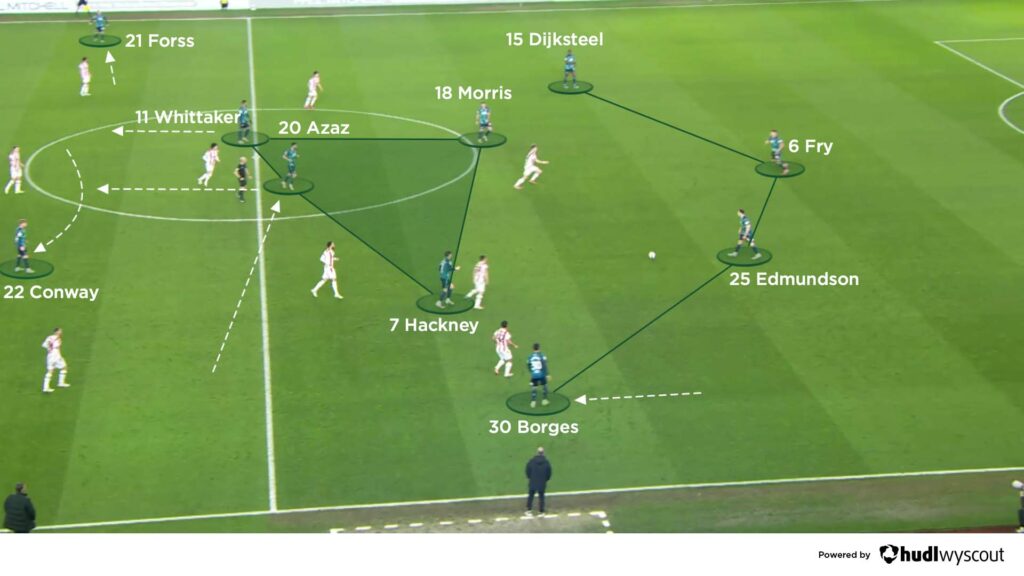

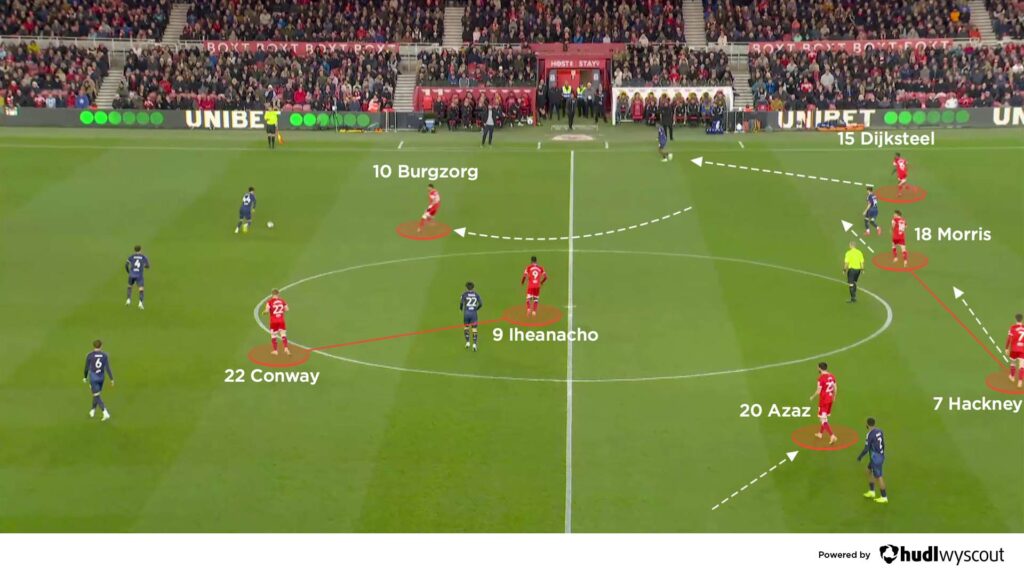

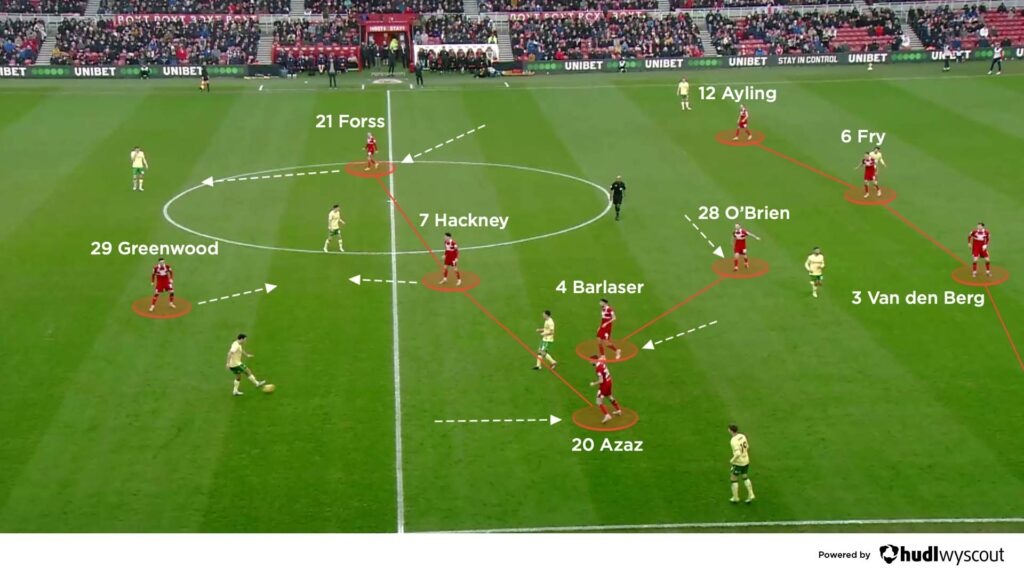

To support Middlesbrough’s central dominance of the ball, Carrick deployed a midfield three but often added a fourth body, with one of the wingers – typically Finn Azaz – moving inside (below). This extra central player was added as early as possible, giving Boro two fluid central attackers ahead of the more fixed double pivot. Again, this opened up regular bounce passes and short combinations, in this case between four central players in midfield. The short passing via the double pivot was so frequent for Carrick that, in 2024/25, Hayden Hackney and Aidan Morris alone played a combined 22 per cent of Boro’s total passes for the entire Championship season. Jonny Howson and Daniel Barlaser provided similar returns the year before, at 17 per cent.

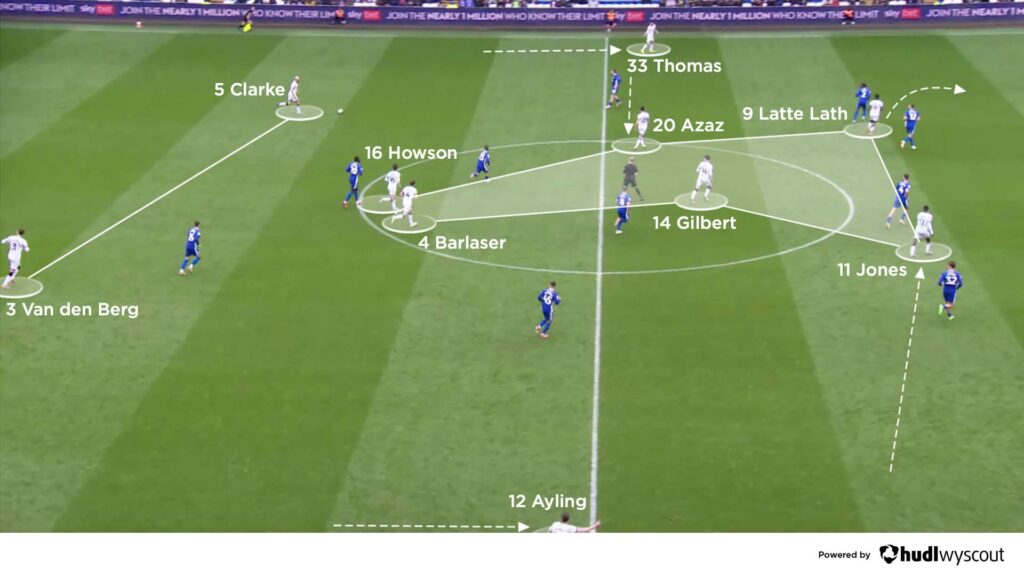

In 2024/25 it was common to see one of Middlesbrough’s wingers hold the width, with the full-back on the far side advancing fast, but late. In response the single centre-forward made runs away from the high winger, mostly on the left – with the right winger staying high – while Azaz on the left narrowed into midfield. The two Boro players between the lines could receive incisive forward passes on the half-turn and also on the move. In the 2023/24 team, both full-backs more often moved forward at the same time, with the remaining winger joining the centre-forward on the top line (below), but Boro still operated with significant central numbers to help progress forward via frequent short passes.

Final-third combinations

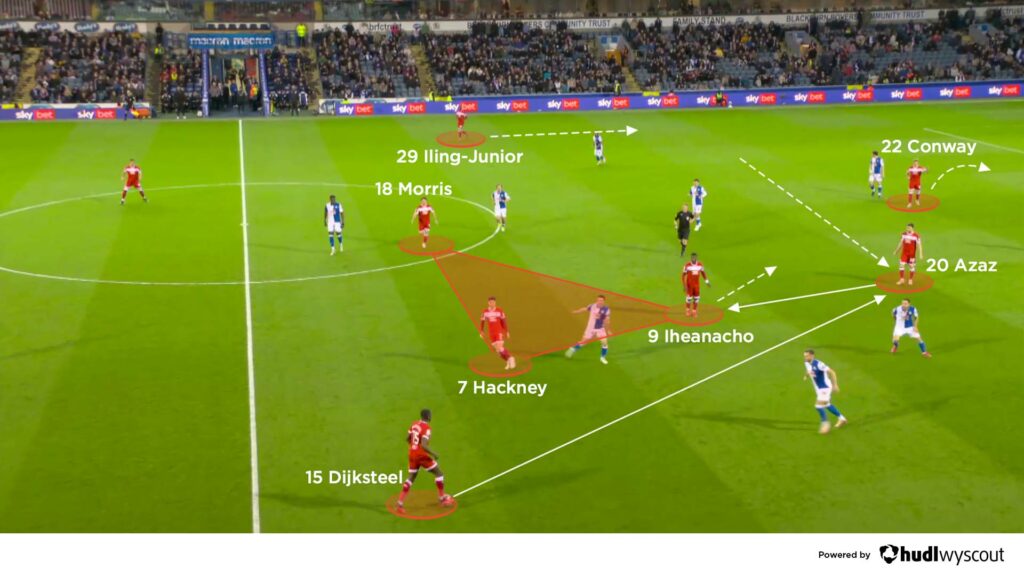

In the final-third Boro’s passing style under Carrick was also evident. They looked for short connections where possible, even when up against congested and stubborn defences, or a low block with significant numbers in place. With at least one of their wingers remaining narrow and joining the number 10, Boro looked to find those players between the lines. The nine looked to stretch the opposition – whether it be Tommy Conway, Emmanuel Latte Lath, or Chuba Akpom – offering the option to play in behind. These runs often forced the opposing back line to drop, creating bigger spaces between the lines for the midfield to receive. Quick passes through – often bounce passes – helped Boro efficiently move the ball through lines (below), with a full-back advancing into space vacated by the narrowed winger, providing an outlet if needed.

Carrick’s passing style was also reflected in play in and around the opposition penalty area. In two of his three seasons his side ranked first and second in the Championship for deep completions – passes that target spaces around 20 metres from the opposition goal. His team didn’t simply lump crosses in at any given opportunity, nor did they play percentage or hopeful balls into the box. While foregoing some of the spontaneity and chaos that can mark that type of penalty-area entry, Boro did work a high number of attempts on opponents’ goals – particularly in Carrick’s final season.

With his wingers content to join the central-passing combinations, Boro’s full-backs provided much of the width in the final third. In 2022/23, left-back Ryan Giles provided a significant number of crosses from the left, as an outlet once the winger had narrowed. As Carrick’s tenure continued, his other full-backs, Luke Ayling and Lukas Engel, delivered significantly fewer deliveries. Instead, with the full-backs holding the width and playing high, Boro worked passing combinations around, trying to lure out opponents. Play back inside saw the double pivot combine with a very narrow attacking-midfield three, with the wingers offering – and sometimes rotating with the 10 – between the lines.

From here, Boro attempted to penetrate with incisive passing combinations, probing their way into the box (below). As a result, Carrick’s side ranked second in two of his three seasons for most touches in the opposition penalty area, with a short-passing style that continued from the back all the way to deep in the final third.

Key coaching points for attacking a low block

• Make the pitch as big as appropriately possible, using height, width and depth as a team.

• Scan and be aware of the four main references – teammates, opponents, the ball and subsequent spaces.

• Support the ball, with teammates positioned beside, beyond and between the opposition.

• Make appropriate movements to create opportunities to receive the ball – small adjustments, as well as longer runs over bigger distances.

• Take care of fundamental passing details – passes should be played with appropriate speed and weight, smoothly into the receiver, well-timed, and to the correct foot.

Defending

Middlesbrough’s short-passing connections and the distance between teammates often being relatively close gave them counter-pressing opportunities, from which they could purposefully transition to attack. Under Carrick they also demonstrated some swift attacking transitions with regains that followed lengthier spells defending in a more reserved block.

But Carrick’s preference for patience, possession, shorter passing and probing final-third play saw Boro’s transitional threat decrease over time. Under his management, Middlesbrough were not consistently a high-pressing team – never featuring once among the Championship’s top 10 for PPDA in his three seasons. Nor were they particularly aggressive with challenges, duels, tackles or interceptions when out of possession. Indeed, they had the division’s lowest challenge intensity in the 2024/25 season.

As such, a large proportion of Boro’s defending under Carrick involved being in a mid-block, tweaking their 4-2-3-1 shape. That included regularly amending the nine and 10 roles. Often they operated as a flat pair defending the centre, while occasionally Carrick would stagger the two – the nine locking play one way, while the 10 man-marked the deepest central midfielder. In some games this pair were used in screening roles that allowed the wide players to jump out more, as the (slightly withdrawn) nine and 10 covered the centre.

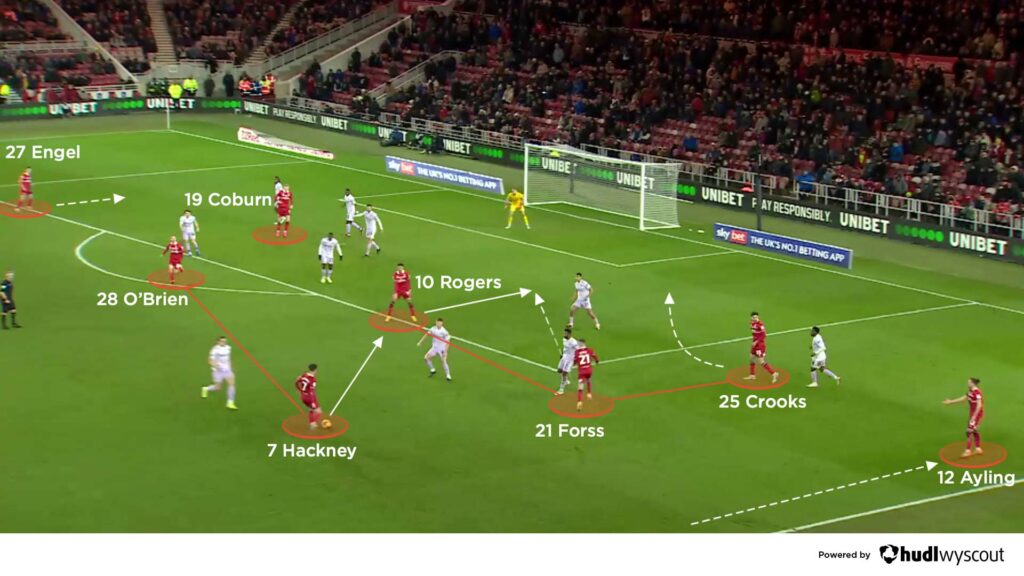

Within the mid-block Carrick’s wide players provided significant defensive support. Often one of the wingers – usually on the right – supported the nine and 10 by pressing outwards, forcing the ball around, or showing it inwards into a central trap. When the winger forced the ball around, Boro’s right-back had to be alert to jump out and support by moving higher (below). This sometimes meant leaving their original direct opponent, with the rest of the back-line then swinging around. In these moments it was important that the closest of the double-pivot moved into the inside channel to stop passes from being reversed inside Boro’s advancing right-back. When it was working at its best, it also meant that Boro’s left winger and other central midfielder squeezed across the pitch to narrow and help cover these spaces.

Alternatively, Boro’s wingers would press inwards. This forced the ball back into the centre, where the nine and 10 could suffocate play, with the help of the double pivot and occasionally the left winger. This often occurred when the ball – initially on Boro’s left – circulated across, with Carrick’s right-winger ready to jump inwards (below). With the nine and 10 also ready to narrow as a pair, and the double pivot also compact and close to the ball, Boro had a nice central trap that was only escapable via very talented or crafty opposing midfielders.

If Middlesbrough dropped back further, Carrick’s defensive shape gradually converted into a 4-4-1-1 or 4-4-2. When in a low block his team looked to show and keep the ball on the sides. The double-pivot was often particularly deep in support of the centre-backs, which could allow access back inside at times, but kept the ball ahead of the back line and central midfield for longer periods.

Whether he employs the same tactics as Manchester United head coach remains to be seen, but his time at Middlesbrough was long enough to give a good idea of the style of play he wants from his teams.

Want to know more about football tactics and learn how to coach from the very best? Take a look at Coaches’ Voice Academy here